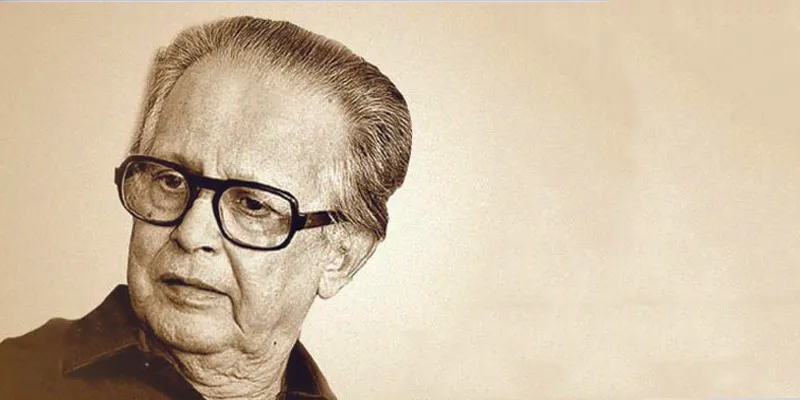

To the man who gave us The Common Man – R K Laxman

Armed with his knowledge, wit, and artistic flair, R.K. Laxman did nothing less than unleash himself upon this country. His bold stance and perspectives on political underpinnings have been admirable through the years, and undoubtedly enjoyed by all – the young and the old, the lay and the proficient. On his 95th birthday, let us delve into the robust life of this satirist, this comedian and this man with an endearing fondness for crows.

Rasipuram Krishnaswami Iyer Laxman was born in 1921, in Mysore, as the youngest child of an Iyer family. Being the youngest was his ticket to being pampered, especially by his mother, whom he was very close to. “I really loved my mother” he recalled in an interview with MoneyLife. It is of no surprise then that his earliest memories of drawing trail back to her. He would follow her into the vegetable market with books, pencils and an inquisitive eye that spared no one. Pencils and paper weren’t a prerequisite for this young artist, and so, a lack of them didn’t stop him. The floors and walls of his home became canvases where Laxman unleashed his imagination. His subjects were sometimes unsuspecting strangers and sometimes his own horrified father.

Due to his father’s well-known and respected presence in the locality, Laxman grew up meeting people of many backgrounds – artists, writers, dancers and film personalities even. Such a rich atmosphere for a curious boy like Laxman undoubtedly fuelled his imagination. Most of his time in school was spent observing other students and teachers. He got himself into trouble once for depicting one of the teachers as a tiger cub. In his autobiography, Laxman recalls another teacher’s response, this time a praise, for drawing a peepal leaf – “You will be an artist one day. Keep it up.” – and the impact this had on him – “I was inspired by this unexpected encouragement. I began to think of myself as an artist in the making, never doubting that this was my destiny.”

As a young boy, Laxman inspired two short stories of his older brother and now a renowned writer, R.K. Narayan – The Regal cricket club and Dodu, the money maker. The latter went on to win a literary award much to Laxman’s surprise because he didn’t know his brother was a writer “till one day the postman delivered a magazine called The Merry Magazine. An announcement in it said that Narayan had won a literary prize for his short story.” Laxman was of course delighted to know that the hero of the story was named after him.

Although Laxman immersed himself in many illustrations and cartoon strips, the work that influenced him the most was that of Sir David Low, a British cartoonist. His was therefore beyond ecstatic when Low came to visit him years later in the TOI office. Publisher J.C Jain recalls, “When I rang Laxman to tell him Low wanted to see him. Laxman almost sank in his chair out of disbelief.”

It was when Laxman was still studying in high school that his father died, unable to recover from a paralytic stroke. This shook his otherwise stable childhood, but he recovered and soon finished his schooling. He knew now for sure that all he wanted was to become an artist. He therefore applied to J.J School of Art in Mumbai for a short art course. He was, however, faced with rejection as the school didn’t consider him talented enough for enrolment. Years later, when he was established in TOI, the same school invited him as a chief guest. Laxman humbly accepted their offer but “was forced to admit in my speech that the institution long ago had turned down a young aspirant from Mysore. But thank God they did: if I had got in I would have ended up in some commercial studio.”

Undeterred by this rejection, Laxman continued drawing while studying for a Bachelor of Arts in the University of Mysore. During this time, he contributed political cartoons to Swatantra, and comic strips to Koravanji, a witty Kannada magazine. The Founder of the latter, Dr M Shivaram, liberally encouraged him, which fortified Laxman’s morale as an artist. He also illustrated some of his brother’s short stories published in The Hindu, for which he received a handsome sum of Rs 2.50 per illustration.

Having now graduated with a degree in Politics, Philosophy and Economics – subjects that, as we now know, piquantly complemented his cartoons to come – Laxman worked for a brief time in the animation department of Gemini studios, Chennai. But he soon lost interest in the work structure and with the money he had saved, headed to Delhi. Once there, he approached The Hindustan Times, where he was, alas, rejected – this time, under the premise that he was too young and inexperienced. Laxman was 25 years old at the time. Albeit disappointed, he heeded the advice of a cartoonist from the paper who suggested he “go and work for some years in a provincial paper.”

En route to Chennai, he decided to stop at Mumbai and look around for prospects – an intuitive decision, in retrospect. Here he met R.K. Karanjia, the Founder of Blitz, which was again a decision made at random. When Laxman drew him a sample cartoon, Karanjia was bewildered at the talent before him. “I couldn't believe that the young man sitting in front of me had such tremendous potential. We were an entirely new paper, and badly required new talent. I gave him a job on the spot.” It was for Blitz that Laxman created the well-known Tantri – the magician.

After a brief association with Blitz, Laxman began work with The Free Press Journal. Here, he worked beside Bal Thackeray, now remembered as the Shiv Sena leader but then as Laxman’s fellow cartoonist. During his time here, Laxman for forced to burn the midnight oil every day because of the challenging workload. In addition to the daily political column, he produced weekly columns called Political Who Is That and contributed to the journal's sister paper Bharat Jyoti . At the same time, he drew for the weekly State's People Supplement and continued to produce work for the Blitz. As Laxman enjoyed caricatures more than he did drawing cartoons, he also produced a large number of it along with more illustrations.

Armed with formidable talent, Laxman worked hard and struggled less. His work went smoothly until one day the Founder, Sadanand, asked Laxman to depict communists in kinder light as the paper was shifting its political allegiance. Laxman, of course, didn’t comply and soon handed his resignation to a sulking Sadanand. He then strode into The Times of India where he successfully impressed – not without nervousness – the intimidating art director, Walter Langhammer, whose only words were, “Now draw.”

Initially, Laxman didn’t draw political cartoons for TOI as the paper insisted on a different style. After two weeks of persuasion, which he did by drowning his editor’s table with dozens of political cartoons every evening, the paper began publishing his political interests, however meagre in amount. It was only in 1950, when the paper acquired its first Indian editor, that Laxman was free to use his natural political tone. It was during this time that Laxman also created a strip called Stars I Never Met for the newly launched Filmfare, which gained immense and long-standing popularity.

During his time in England, that he visited a few years later, he met and drew caricatures of prominent figures such as Bertrand Russell, Graham Greene, J.B. Priestly, and T.S. Eliot. In his autobiography, Laxman recalls how T.S.Eliot “sat still, as if posing for an oil portrait. I made an elaborate pencil study of him. When I finished I held it out for him to autograph. He continued to sit without stirring. I had to clear my throat loudly, for he had gone to sleep. He woke up with a start and looked apologetic. He gazed at my drawing with amusement and signed it cheerfully.”

After years of politically themed cartoons, TOI’s general manager believed that Laxman’s tone had become just that – too political. He therefore suggested depicting the perspective of a common man. Thus, the most renowned of Laxmans’ creations entered the stage through his daily cartoon strip, You Said It. “The bespectacled Common Man in his checked coat had walked into my cartoon spontaneously, as if I had no hand in his creation. Equally effortlessly he became a silent spectator of events…” Such a perspective resonated with the public in ways that Laxman had never anticipated. He was “surprised to discover that my readers looked upon me not merely as a cartoonist who tickled their sense of humour, but as a profound thinker, a social reformer, a political scientist, a critic of errant politicians and so on. I received letters complaining about postal delays, telephones, the sloppiness of municipal authorities, inflated electric bills, bribes in school admissions.”

Laxman received the Padma Bhushan in 1973 from Prime Minister Indira Gandhi for his distinguished services. He was, however, taken aback by this news. “I was stunned; here I was attacking and making fun of her in my cartoons, and she had seen fit to confer this honour on me! I suspected a catch in this somewhere!...I asked for a little more time to decide... Finally I agreed to accept the honour.” In 2005, he was also awarded the Padma Vibhushan.

Laxman lived a rich life for 93 years before he died in 2015 due to multiple organ failures. For a man who said “Nothing in my life’s been intentional, it’s all accident,” R.K. Laxman made a life for himself with the sole, yet simple, intention to draw. The country’s grateful for all the “accidents” that have given us this iconic man.