Skin irritations, respiratory diseases and death; how the manual scavengers of India continue to suffer

Despite the ban against it, manual scavenging is still a very disturbing reality.

“My mother used to head out with a basket full of ash every day. She would visit dry latrines in the area one by one, sprinkle the ash on the night soil, scoop it up, and carry the excreta-filled basket on her head to dump the contents into a small tanker. This was almost 40 years ago, in our 'Singara (beautiful) Chennai',” recounts Ravanaiah. Born into a Madhiga family, Ravanaiah occasionally even accompanied his mother.

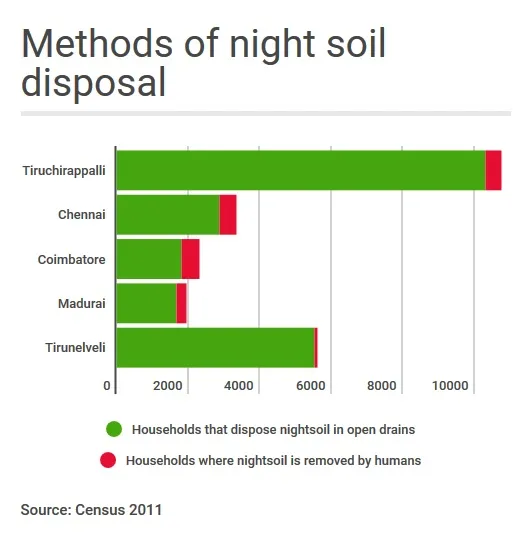

Though people no longer carry excreta on their heads anywhere in Tamil Nadu, the practice of manually handling and disposing of human feces is very much prevalent in many parts of the state, including the capital city of Chennai.

The Madhigas, a sub-caste of the Adi Andhras, are a Telugu-speaking community whose members have been employed as scavengers by the administration for over a century now. “But scavenging was not our traditional occupation. Our ancestors were leather craftsmen. Considered as untouchables even among Dalits, we did not have an option but to comply with what was thrust upon us,” he rues.

As in most other states, the occupation of scavenging is almost always reserved for Dalits. In Tamil Nadu, the most disadvantaged among Dalits – the Madharis, Chakkiliyans, Thoti, Madhiga, and Adi Andhras, collectively known as Arunthathiyars in Tamil Nadu – were charged with such tasks. Ravanaiah, however, broke out of this degrading tradition, and now works for the upliftment of his people through the Tamil Nadu Adi Andhra Arunthathiya Maha Sabha.

Scavenging in Tamil Nadu

Despite the state’s impressive toilet coverage stats, the practice of manually disposing of human excreta persists, covertly endorsed by corporations and panchayats. Open defecation (OD) and manual scavenging are everyday realities even in metro cities, regardless of how vehemently the administration denies it to save face. The ever increasing migrant population and the resultant mushrooming of slums have left the city sanitation in shambles.

The Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavengers and their Rehabilitation Act, 2013, while defining a ‘manual scavenger’ as someone who manually cleans, carries, or disposes of human excreta, fails to include those who work with ‘protective gear’ under its ambit. The corporation swears by the measures it has taken to ensure safety. The reality, however, is different. “Take a look around and see if you can find any sanitary worker cleaning toilets wearing gloves or entering septic tanks with gumboots. Gumboots and gloves are almost ceremonial; workers are made to wear them when inspectors and officials come visiting,” explains Ravanaiah.

More often than not, boots, gloves, and reflective jackets are purchased in bulk, regardless of the users’ frames. “Officials say that we are supposed to work only with rubber gloves and not with bare hands. But it is impossible to grip anything with these over-sized gloves; we toss them out,” says sanitary staff L. Sundaram. As the inconvenience of using such protection overrides visible benefits, workers feel it is better to get done with their tasks quickly, sans protection, rather than fussing over inappropriate masks and oversized boots.

Bad air, bad health

The 18th century Miasma Theory, widely accepted in most of Europe during medieval times, proposed that the cause for all illness was exposure to ‘miasma’ or bad air. Though the role of miasma as the sole cause of disease has since been disproved by the theoretical evolution of medical sciences, it helped establish the immutable connection between poor sanitation and ill health.

Human feces turn into a toxic cocktail of sulphide and volatile gases when left to be digested in the absence of air. Septic tanks and underground sewers are replete with gases such as hydrogen sulphide, methane, and carbon monoxide, by-products of organic decomposition. Hydrogen sulphide (H2S) being highly corrosive, the septage management rules, in no uncertain terms, instruct the administration to ensure the use of sulphur-resistant cement to prevent physical damage to the structures owing to corrosion. “Hydrogen sulphide can corrode concrete. And still, our men enter sewers with absolutely no protection,” rues Director of Change India, A. Narayanan, who has been fighting for the rights of manual scavengers in court.

Low concentrations of the gas irritate the eyes, nose, and throat, causing respiratory distresses. Headaches, dizziness, and nausea increase with increased exposure. H2S results in ‘olfactory fatigue’, where the brain loses its ability to distinguish the smell, and over time, the entire stimulus gets de-sensitised. This fatigue is one of the main reasons behind men losing consciousness in septic tanks. The presence of the gas goes unnoticed by the olfactory sensors, and when the H2S accumulation in septic tanks or sewers exceeds 300 parts per million (ppm), the gas gets absorbed by the lungs rapidly, causing unconsciousness and increased risk of death.

A resident of Tiruvottiyur, L. Siddhayya has been a scavenger for the Corporation of Chennai for over 15 years. Until four years ago, he would enter the sewers to unclog blocks and desilt them for a daily salary of Rs 140. “I still unclog sewers, but no longer enter them. I work from the outside now, using only long rods and sticks. There have been too many instances of people being hit by toxic fumes; you don’t want to get killed by toxic fumes now, do you?” he quips.

Aches, infections, and alcoholism

The threat of contagious infections is something scavengers have learned to live with. In the absence of appropriate protective gear, a simple scrape or a needle poke could put workers at risk of acquiring bacterial and viral infections like leptospirosis and hepatitis. Skin diseases are commonplace. Sanitary worker Saravanan’s biggest complaint was relentless skin inflammation and itchiness during his sewer cleaning days. Yovaan from Tiruvottiyur, too, suffered from skin infections. Both claim to have left entering sewers and work only with iron rods and ropes to unclog drains.

Alcoholism and the use of tobacco is deeply rooted in this profession. No person, in his senses, would get into a closed, smelly pit filled to the brim with filth. Many claim that alcohol is almost a necessity, to dull their senses before entering muggy sewage-filled pits. This behaviour, however, is hard to condone, as it aggravates the risk of unconsciousness in gas-filled chambers, not to mention the socio-economic aspects of alcohol addiction in general. “Most men spend close to a third of their earnings on alcohol, certainly wasteful, considering the fact that most families live in penury. And alcoholism can never be considered in isolation; it is almost always accompanied by domestic violence, fostering dysfunctional family dynamics,” says Narayanan.

For many, tuberculosis and asthma are lifelong companions. Muscle-aches, headaches, and fever are so customary that they fail to raise alarm. Perumal, who had been working in the sewers for almost 16 years until a few years ago, recounts his frequent visits to the doctor. The only motivation for sticking with the job, he says, is the belief that one day he’d become a permanent employee of the corporation. That day is yet to dawn, and perhaps never will in his lifetime.

Perumal is not alone. Since manual scavenging is prohibited by law, the corporation no longer recruits scavengers on a permanent basis. Instead, the work of unclogging sewers and drains is contracted out. A contract employee receives a fixed sum of Rs 6,000 per month, whereas a permanent employee would be paid around Rs 14,000.

In most cases, the tradition of sanitary work is passed from parent to child. In the absence of alternate employment options – due to both educational and social deficiencies – many continue to be stuck with what they have been bequeathed.

Crime and compensation

No wonder, then, that not a single arrest was made under the Employment of Manual Scavenging and Construction of Dry Latrines (Prohibition) Act, 1993, the precursor of the 2013 legislation. Passed two decades apart, both laws sought to eliminate the use of unsanitary toilets, and thereby manual scavenging, though the 2013 Act is much more stringent in terms of coverage. The Indian Railways and Cantonment Boards have been brought under the law’s ambit. However, no concrete measures have been laid down to ensure rehabilitation; monitoring and implementation mechanisms lack clarity and continue to remain lax.

The government washes its hands of workers’ deaths that occur on private property, individual household and apartment septic tanks. Very often, the death of scavengers working for the corporation is slighted, and the victims’ families are left waiting for any compensation. Narayanan has been filing Public Interest Litigations (PIL) in the High Court of Madras to ensure the victims’ families receive the compensation – Rs 10 lakh for accidental death – promised by the law.

Narayanan has been pushing for a National Institute for Sanitation Research and Technology to be set up to address the issue of sanitation in its entirety. “Research still revolves around civil engineering, whereas the subject is much more than that. Basic sciences, social sciences, and technology are integral aspects that often get overlooked. The need for manual scavenging can be greatly eliminated by employing appropriate technological solutions depending on sewage volume, constituents, and geology,” he adds.

It would make more sense to bring all septic tank waste-handlers into a single fold, holding the corporations or the authority designated for the purpose responsible for any mishap. Manhole dimension and design need major reworking. Narayanan complains that the opening is so small that when a person dies in a sewer, it take the fire services’ staff hours to take the body out, as the body bloats up very quickly from being exposed to the concentrated filth and gases.

Gloves and gumboots aside, isn’t it the same set of people being deployed to clean public toilets and sewers, I ask. “Education changes everything. Our children are in schools and colleges now, and we are determined to keep them away from the filth and discrimination,” responds Ravanaiah emphatically.

Disclaimer: This article, authored by Seetha Gopalakrishnan, was first published in India Water Portal.