‘He went mad after he woke up’- experiences of black terror in Andaman’s ‘Kala Pani’ jail

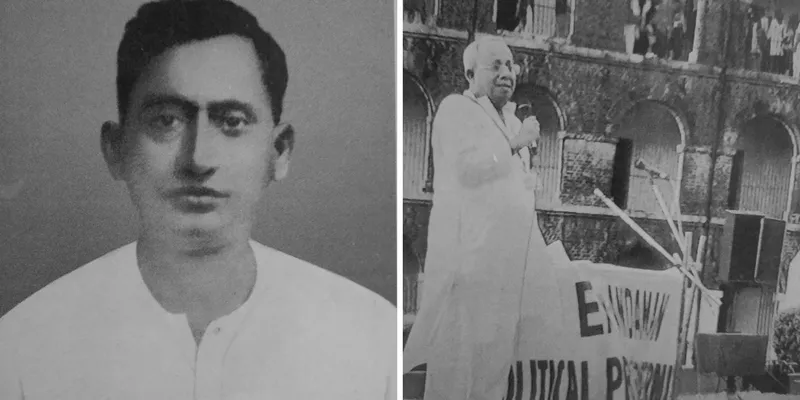

Known as Kala Pani or ‘black water’, Cellular Jail in Andaman & Nicobar Islands was constructed in 1896 and opened by the British in 1906 to exile political prisoners in remote isolation. Anup Dasgupta, son of Sushil Kumar Dasgupta who was one of the imprisoned revolutionaries, narrates his father’s experiences in prison.

When I first visited Cellular Jail as a 12-year-old, it appeared as an imposing structure of brick and iron. More than a decade later, the jail still looks imposing. But this time, its stories hold more meaning and inspire awe because they are narrated by the descendant of one who haswitnessed the black terror of this prison.

Revolutionary

Over samosas and rasogollas, I talk to Anup. Now in his 70s, with a shock of gleaming, white hair and a smile on his face, he tells me the story of his father who had once known darkness inside this prison.

Sushil Kumar Dasgupta (1910-1947) was born in Barishal, now in Bangladesh. He was a member of the revolutionary Yugantar Dal of Bengal, and the Putiya Mail Robbery case of 1929 took him to Medinipur prison. From there, he escaped along with fellow revolutionaries, Sachin Kar Gupta and Dinesh Majumdar.

Cooks, sweepers and postmen were always of great help to the freedom fighters. A cook brought them a huge, metal ladle. They beat the ladle till it bent, and flung it over a wall as one would do a hook. They tied knotted cloth to the bent ladle, and climbed the makeshift ladder up over the wall

They were absconding for seven months. Eventually Dinesh was caught and hanged, Sushil was sent to Cellular Jail, and Sachin first to Mandalay Jail and, then, to Cellular Jail.

Black terror

The prison originally had seven wings that spread out from the central watch tower, in seven directions. The watch tower housed the alarm bell and guardsmen kept an eye on the prisoners. The model is in style of Jeremy Bentham’s concept of panopticon which gives prisoners the impression that they are being watched even when they are not, by virtue of mere visibility of all portions of the prison from its centre. Michel Foucault, the renowned French philosopher, later identified the panopticon as a symbol of surveillance. Three of the seven wings still remain.

Surveillance was intended to be the key foundation at the jail which derived its name from the small, individual cells that housed prisoners. Each of the 693 cells were of 4.5 m x 2.7 m dimension, with a ventilator at a height of 3 m in the back wall. The front corridor of each wing faced the back wall of its adjacent wing so that prisoners could not communicate in any way at all. Of the three-pronged strategy of hunger, torture and isolation, it was the third that was intended to be the harshest punishment.

Food at Cellular Jail was rice which was more dust, rain water, and wild grass. There were no beds. Inmates were whipped if they spoke to each other.

The gallows were open. Beneath each noose, lay a small trapdoor. The trapdoor would give way as soon as the noose tightened around the neck of an unfortunate freedom fighter. He would then hang painfully to death. His body was then released into the pit under the trapdoor. The pit was connected to the sea by a passage. The journey along the cold, dark, damp passageway was all the last rites a martyr would receive.

Read More:

How transgender rights activists are addressing the gender struggles of rural India

‘Our lives are all about hard work and paying rent’, The woes of migrant women in Bengaluru

Scotsman David Barry, the jailor between 1909 and 1931, was infamous for his insane cruelty. “While you are here, I am your god,” was the cry with which he welcomed prisoners. In the central courtyard stood a long work shed, the remains of which still exist. It had a pestle to extract oil. Prisoners were harnessed to the pestle - they moved round and round in circles, and oil trickled out of seeds.

Cellular Jail used a variety of fetters. Barry once asked Ullaskar Dutta to glean three litres of oil in a day. Ullaskar refused because even oxen can glean only two litres a day. They fettered his arms raised to the ceiling, and his feet to the ground. He stood motionless for three days for he could not move. When they untied him finally, he collapsed senseless. He went mad after he woke up, narrates Anup.

Hunger Strike

In 1933, the prisoners went on a 45-day hunger strike. From the ninth day, guards tried to force feed them with milk. In an effort to resist this, Mahavir Singh Gaddar of Punjab and Mohit Maitra and Manakrishna Nabadas of Bengal struggled to death. The others found that their pots of water had been stealthily replaced with pots of milk. “What should we do?!” an agitated Sushil asked his neighbouring prisoner, Dr. Narayan Ray. “Haven’t you ever played football?” came the reply. “Kick it!” The words echoed and passed from cell to cell. Very soon, a stream of milk flowed out from the cubicle-like cell of Cellular Jail.

In the end, the British relented and accepted the prisoners’ demands which were as follows:

- We want soap to clean ourselves.

- We want beds to sleep on.

- We want edible food.

- Let us study for we are political prisoners.

- Allow us to communicate with each other.

Gradually, an academic environment grew within the premises of the jail. Prisoners studied political science and history under Satish Pakrashi, Shiv Verma and Bhupal Bose. “I don’t know why, but it is the British who gave these prisoners Das Kapital to read. That is how our freedom fighters learned Marxism,” says Anup with a laugh.

In 1937, another hunger strike ensued, this time for 36 days. Once again, the British had to give in – the prisoners wanted to return to their own soil to partake in the last years of the freedom struggle. They were sent home between September 1937 and January 1938, and Andaman’s Cellular Jail was shut down forever.

Enter the SocialStory Photography contest and show us how people are changing the world! Win prize money worth Rs 1 lakh and more. Click here for details!