How Ganesh Utsav became the festival of the masses

The huge pandals, gigantic statues and mass participation during the 10-day festival developed around nationalist fervour against repressions of colonial rule.

The air is thick with vermilion. Bare-bodied boys and men of all ages are dancing to the rhythm of the beating drums and trumpets. Wooden pandals with fragrant incense sticks are a common sight. India is getting ready to welcome Ganesh, the elephant-headed god of the Hindu pantheon.

As we travel back in time, we learn that the Ganesh Utsav revelry is a century-old tradition. The colossal pandals, monumental statues and mass participation developed around nationalist fervour against the repression of colonial rule. Ganpati bappa morya became a chant for the masses. Festivities emerged from households into a public domain, and the 10-day carnival brought people from different ranks together.

The birth of Ganesha was also celebrated by ancient kings of Satavahana, Rashtrakuta and Chalukya lineage.

In the 16th century, Marathas gained a strong foothold, and Chhatrapati Shivaji initiated the festival to foster a spirit of brotherhood and culture in the community. Since then, Gajanan became a part of the Peshwa’s culture and a family deity for Maratha households.

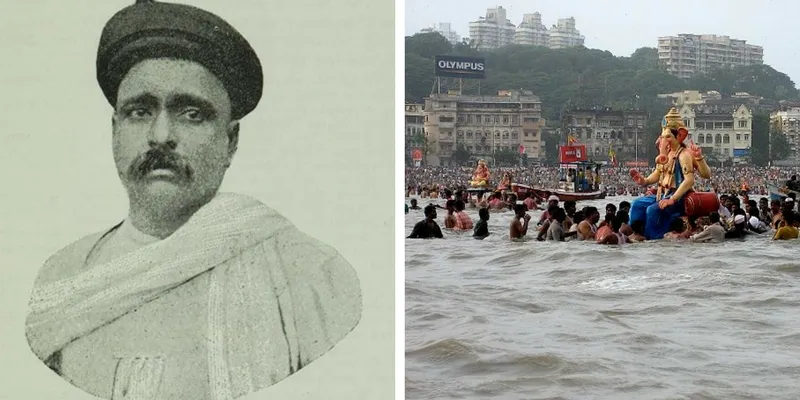

The redefining of Ganesh Utsav took place in the late 19th century and the credit goes to Bal Gangadhar Tilak, the “father of Indian unrest”. He revived the festival with a patriotic spirit amid the despotism of the British Raj.

In 1892, Tilak brought the festivity from homes to streets of Pune, at a time when public social and political gatherings were banned by the British.

This festival also served as a meeting place for common people of all castes and communities. It slowly became a religious and social function. The tradition of large hoardings with images of the god and immersion of Ganesh statues on the last day of the festival were started by Tilak.

Read More:

This Ganesha idol hack is truly disruptive

In 1893, Tilak took the celebration to Bombay. The Keshavi Naik Chawl Sarvajanik Ganeshotsav mandal, in Girgaum, is where the oldest and first pandal was set up. Over time, the streets of Mumbai and Pune turned into venues for the 10-day celebrations and huge gatherings of devotees.

By doing this Tilak channelised the patriotic spirit and was able to use festive fervour to create a feeling of unity among the masses against the British. Most of the time, the singing, dancing and drama that was part of the gala was centred on nationalism and independence.

The theme changed during the 30's and 40's, when the world wars dominated human consciousness. The 70's and 80's again reiterated nationalist spirit as India waged wars with China and Pakistan.

After Independence, the festival also took on a political hue.

Political parties made huge donations and sponsorships to local pandals to woo youth who had influence in their areas. This would later help in the election campaigns.

The evolution of the festival can be seen in 1982, when a body for pandals was established. This was done by the Maharashtra government after increased conflicts between different groups. The first count of total Sarvajanik Pandals in the Bombay was more than 1,340. In 1995, there were around 3,000 of them while in 2016, there were around 12,000 pandals.

Bringing Ganesh home is a tradition that is by, of and for the people. Let's all celebrate that spirit.

Enter the SocialStory Photography contest and show us how people are changing the world! Win prize money worth Rs 1 lakh and more. Click here for details!