How Akiba is cultivating the maker-hacker culture in the countryside

Chris Wang a.k.a. Akiba is our Techie Tuesdays’ candidate for the week. He’s the founder of FreakLabs and Hackerfarm and focuses on building mixed (tech+non-tech) communities across Japan, India, and China.

Chris Wang has devoted most of his life in wireless and communications domain. So much so that people started calling him Akiba, an abbreviation for Akihabara which is an area known for its electronics market in Tokyo, Japan.

But it’s not pure technology that interests Akiba. He looks for context — the reason why he chose Physics over Maths in college or why he is building a community of techies, artists, and performers. Akiba (he prefers this name) runs Hackerfarm — a community of hackers and makers in the Japanese countryside. He also manufactured environmental monitoring sensors at Freaklabs, a company he started in 2007. His association with India started in 2012 when he came to Dharamshala for a workshop through UNESCO.

Here’s Akiba’s interesting story from Silicon Valley to Japan, China, and India.

Discovering his first love — dancing

Akiba was born in the US in Orange County in Southern California and grew up in a relatively poor area called Santa Ana in California. Akiba’s parents were Chinese. There was a lot of pressure on him to get good grades in school. But by the end of high school, he started hanging out a lot with his friends and going for parties. He started dancing and really enjoyed it.

In fact, he even dropped out of college for a while to become a professional dancer. But being a professional dancer was a tough life, so eventually he decided to go back to college. Akiba got a degree in Physics from the University of California, Irvine (UCI). He says,

I enjoyed Maths, but Physics gave Maths more context. The need for context is very important for me and it is there in the other aspects of my life too.

The dot com boom

After graduation, Akiba realised that without a PhD, his degree won’t get him a job. So, he pursued Applied Electrical Engineering and graduated in 1997, around the time of the dot com boom. Getting a job was relatively easy then. He started working on FPGA (field programmable gate array) design. After a year and a half, he moved to another company to work on innovative circuits (ICs). Akiba found working in startups more exciting.

Over the years, he has specialised in communications — protocols and circuitry. Initially, he was working on videos but then moved to ADSL, XDSL which was telecom. Later he worked on USB and was a part of USB standards committee which pushed out USB OTG standard. He says, “There has been a constant thread of protocols and communications in my work throughout.

You may also like – Story of a programmer who fell in love with Hindi poetry — Satish Chandra Gupta

The stress buster — Japan

Akiba found IC design stressful and wanted to move away from California. So, in 2002, he decided to move to Japan to be with his Japanese girlfriend. It was a big change for him. He recalls, “It was a culture shock for me. I had to learn a new language.”

Akiba’s previous company rehired him for sales/business development, but he dint like the work. He says, “I hated it. It almost made me an alcoholic, but taught me a lot of things about business for which I’m thankful now.”

Akiba quit his job in 2007. At that time, there was nothing to make him stay in Japan, but there was also no reason for him to go back to the US. He decided to start FreakLabs which was focussed on writing open source software — Zigbee. However, it was difficult as Japan wasn't very friendly to startups (in 2007) as compared to the big established companies like Panasonic, Sony. Akiba says, “Unlike the US or China, if you're just a one man show trying to do business, people may not take you seriously.”

FreakLabs — of mistakes and lessons

Zigbee (mostly based on 802.15.4) came out from the protocol IEEE 802.15.4 (wireless sensor protocol) on which Akiba was working with his professor friend. He realised that people was selling Zigbee protocol stacks but one couldn't find a source code for that so he started writing open source software. Only later he figured that Zigbee was so complicated that even when the software was free, people dint want to use it because they dint know how to use it.

Akiba was also selling hardware boards to test his software. This was much easier than selling software. But he dint realised that he had already started a manufacturing company, once he decided to build boards and sell them. To ramp up, he spent a lot of money on inventory and automated equipment. Unfortunately, there wasn't much demand and a lot of this inventory couldn't be used. Akiba lost a great amount of money in the beginning.

Meanwhile in 2008, along with a few friends, he started Tokyo hacker space.

Also read – Meet Joydeep Sen Sarma, the IITian who revolutionised big data at Facebook

When Akiba met Masa Son

In 2011, Akiba had to start consulting again in order to make money to survive. However, when a big earthquake and tsunami hit Japan, a lot of things changed. People thought that living in Tokyo might get even tougher, when the radiation cloud went over the city. Akiba and his friends at HackerSpace decided to measure the radiation from a radiation monitoring network.

This was the beginning of Safecast. Akiba designed the radiation sensor Geiger Counter that was networked and could upload the data to the internet. He used them (Geiger Counters) to monitor the radiation around Tokyo which caught the attention of some other people who joined Akiba at Safecast.

At that time, Softbank wanted that capability to be developed all across Japan. So, the head of Softbank, Masayoshi Son, gave Safecast a million dollars to set up a large set of radiation sensor network (350 nodes) across Japan. Towards the end of this project, Akiba realised that Safecast ended up becoming too large and had grown very fast. He then decided to move on.

Building communities — technology with context

Akiba went to China in 2012 to teach a course on manufacturing at MIT Media Labs. He took a lot of students to the factories to teach them about the basics. That was the first time he went to the small factories and noticed how vibrant the things were.

The same year, he also got a chance to visit Dharamshala, India, through UNESCO to teach a workshop on wireless sensors. He adds,

We were setting up water sensors to monitor water levels in large water tanks to solve the water problem in the area. That gave a lot of context. I knew that I was not just developing a wireless software, but something that could affect people's lives.

At Dharamshala, Akiba taught people how to get the sensor data, communicate it wirelessly, and then get it to the internet. After that, it could then be fed to the Pachube service (now known as Xively.com). He, along with the support of his Indian friends, started HillHacks — a hacker conference in Dharamshala. This made him keep visiting India (Dharamshala) frequently. He says,

People (networks) in Dharamshala were constantly getting hacked by the Chinese (govt) because of Tibetan affiliations. So, we wanted to get information security people in Dharamshala through a conference like HillHacks.

Initially, Akiba paid most of the money for HillHacks out of his own pocket. He even located a source in Tokyo for cheap laptops and shipped 50 of them to Dharamshala along with some other hardware from China.

After this, Akiba started seeking a lot of other projects. Few of them were the monitoring of Mangrove forests in Costa Rica and radiation monitoring in Indonesia. He also consulted International Atomic Energy Agency.

Tech stack for wireless sensors

Wireless sensors use fairly large technical stack. It requires a lot of domain specific skills. Akiba developed the hardware platforms himself based on Arduino. He says, "Since these sensors and devices are used by scientists, it's important to make them as accessible as possible and Arduino does a good job.”

For an aggregator, he switches between 3G, Wi-Fi, or ethernet. On top of that, he uses Pachube (where data was fed). Data is then visualised in charts and dashboards. He encourages to build your own platforms using Python (or other languages) because the there's no guarantee of retrieving the data once the third-party services (to analyse/process and visualise data) stop.

So, the tech stack includes basic hardware (wireless and power management) on which there’s Arduino (firmware) and gateway and another communications stack. Then comes the server backend and the database management. Then comes data cleaning, analysis and processing. After that, data visualisation is created which can be done in a fancy or a simple way. The front end is in Java script.

Meanwhile…

Few years later, Akiba was recruited to lead a hardware team to design DNA sequencing equipment. The money he earned allowed him to set up Hackerfarm — a hackerspace with context in the countryside in Japan. Akiba remarks,

Technology with no context has almost no meaning. This is also what you see in the Silicon Valley (technology without context).

Hackerfarm focussed on agriculture, technology, and sustainability. Since the costs of running it in the countryside was low, his runway became huge.

Akiba and his friends at Hackerfarm do environmental monitoring through outdoor sensor networks. They work on building rugged devices (with sensors) which can transmit long distances. Akiba believes that the most crucial thing in developing wireless sensors is power consumption/management, i.e. how much less power your device can consume. Sensor accuracy and transmitting range are other vital factors.

“The purpose of Hackerfarm is to demonstrate that there's an alternative to life in the city and the corporates. Our measure of success is the extent to which we work to solve real-world problems,” says Akiba.

Hackerfarm recently sent solar lanterns to Puerto Rico which lost its power due to the hurricane. It turned out to be a much larger project than Akiba thought it would be.

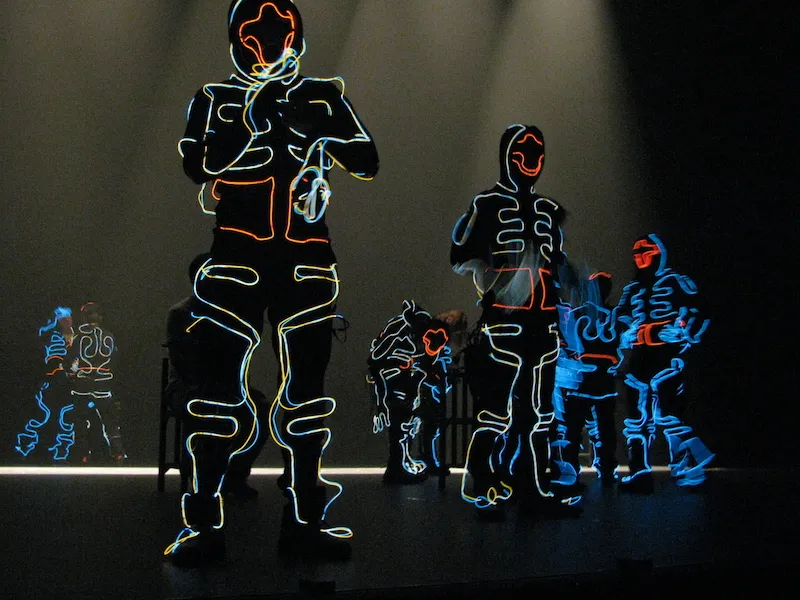

Akiba is also working with dancers to make illuminated clothing for them.

Of community building, values, and future

Akiba doesn't deliberately try to build tech communities as he likes to have mixed communities with techies, artists, musicians, performers and others in it. He believes that communication is the most important aspect of building good communities. He comments,

You've to communicate clearly your ideas and vision and other people should be comfortable sharing theirs.

Akiba believes that being genuine helps you in discovering who you really are and in respecting other people as well.

In future, Akiba wants to start developing performance technology for dancers as a separate product line and plans to take up more projects like Hackerfarm.

You can find Akiba on Twitter.

Trivia: Akiba’s original reason behind renting the countryside place was to make cheese but he couldn't source milk so he had to give up on that idea.