Where there are no sewers: a day in life of Lucknow's toilet cleaners

This World Toilet Day, we turn the spotlight on the sanitation chain, on those who clean out latrines where there are no sewers to carry away the waste.

November 19 is World Toilet Day.

Since World Toilet Day was first declared in 2001, much progress has been made in the global effort to provide safe and affordable toilets for the world’s citizens. Significant strides have been made in ‘reinventing’ toilet designs for low-income, water-short, unsewered urban zones; celebrities such as Bill Gates and Matt Damon have brought this once-taboo topic to the open; and the Prime Minister of India--the country with the highest number of people still practising open defecation--publicly declared his country needed toilets over temples.

Well over two billion people today lack access to basic sanitation facilities according to the World Health Organization, and about 760 million of them live in India. The goal of this day is to make the global community aware of the right to safe and dignified sanitation, and support public action and policy to bring this right closer to those who do not enjoy it. This World Toilet Day, we focus on the back-end of the sanitation chain, on those who clean out latrines where there is no flush or sewer to carry away the waste. This work, done without mechanical equipment and protective clothing, scooping out faeces from ‘dry’ latrines and overflowing pits, is called “manual scavenging”.

It’s an ancient profession and India, which made the practice illegal in 1993, still has over one million such cleaners (the exact number is unknown, but declining). They come from the lowest strata of the Hindu caste system, and about 90 percent of them are women. Despite valiant civil society (and several government) efforts to train them for other professions, breaking out of this denigrated caste-based profession remains difficult. Many mehters live in the shadows of society, invisible yet reviled, taunted yet essential, trapped in an unconstitutional practice without viable alternatives.

In a sense, 70 years after Indian independence, this is a community still waiting for its freedom. In this photo-essay, we explore the daily lives of the toilet-cleaners: their homes, their hopes, their work, and their determination to get their children out of it.

If World Toilet Day is about expanding access to clean toilets, it must also be about those who have to clean the toilets.

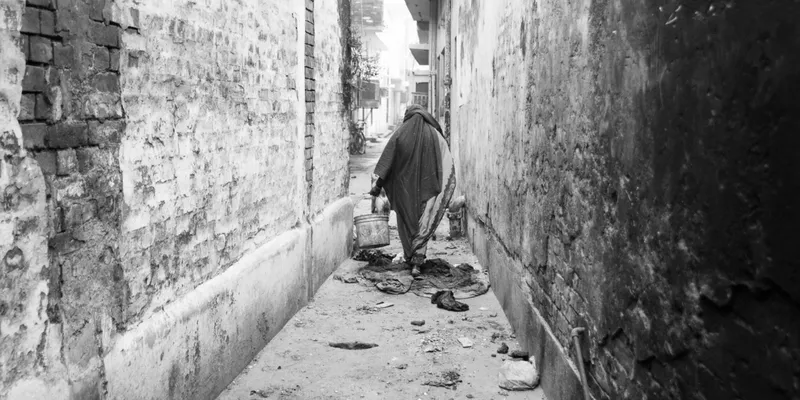

It's December and we're in Lucknow. Old Lucknow is a city of medieval architecture and narrow alleys. The alleys are crowded, with gutters on either side that drain away everything--rainwater, bath water, kitchen waste, human excreta. The streets have no sidewalks. Most people are indoors, but those who pass Rajan either don’t see him or say nothing. He’s cleaning out a household toilet in broad daylight, his socks and flipflops protecting his feet from the cold and the muck.

The excreta is loose, so it takes several attempts to clean it all out. When he’s scooped everything into his bucket, he carries it down the alley and tips the waste into the gutters on the side. The yellowish sludge dissolves into the watery blackness.

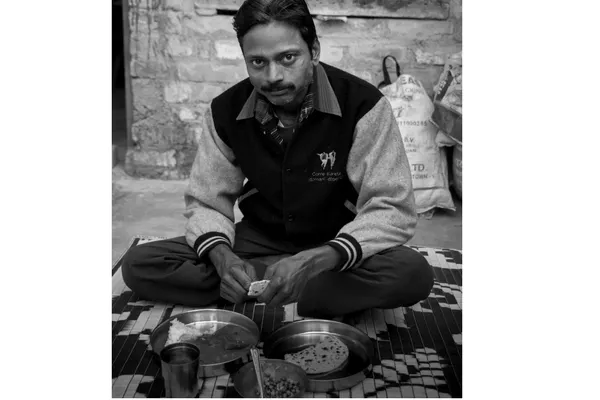

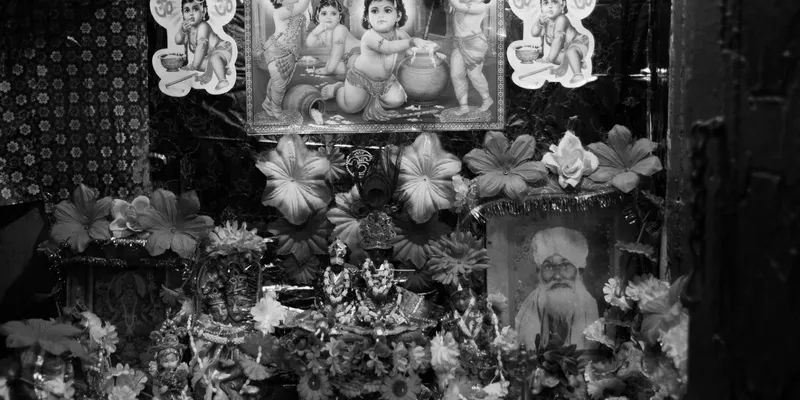

Rajan is from the Valmiki caste, and inherited his job when he was just 14 years old. He lives with his wife and sons in a two-room house, with a small main room leading to an even smaller kitchen. The house is right next to an open drain, but is spotless inside.

With young children to look after, Rajan’s wife works as a part-time domestic help. She goes into her immaculately-maintained kitchen and starts making tea for her guests. As she pours the milky tea into three tiny steel glasses, Rajan looks at the number of glasses and says he doesn’t want any.

Rajan doesn’t want his boys to take on the family profession. Except for the little one, they all go to school. The second one is especially bright, and plans to be a bike mechanic, he says.

People from this community will do just about anything to make sure their children are educated. Kishen and Meena, like Rajan, have pinned their hopes on education for their children. They both clean toilets. Their house is just a room, 15 feet by 10 feet. At one corner, there’s a small kitchen-like setup. The house is lit by a single lightbulb, but the toilet is a porcelain pour-flush one, clean and dry.

Their problem is TV, they say; the children don’t touch their homework when the Hindi soap operas come on. “These children think that education is free. Education is free only in government schools. I save up every month to send both my children to private schools.” Meena is proud and worried at once. The children go to a Christian school, three km away from home. “Better to send the children to a school a bit far away from where we work. If other children get to know the child’s caste or the parents' occupation, they bully our children.”

This evening, Kishen and Meena are back from a full day of work. They wash, then settle down to dinner--roti and dal. “You know, when you start doing this work, it is difficult to eat dal for a couple of months,” Kishen says. “Anything yellow makes you sick.”

Meena moves closer to the fire and suggests some tea; she hasn’t had any all day. It’s not that there’s no time; But, “we don’t eat or drink until we’ve washed ourselves. Cleaning the shit of these people is bad enough. I don’t want to put that in my mouth.”

The next morning, just after 7am, we go out with Vasumati. Her husband doesn’t want her to do this work. “But we have two children and we need money for their school, for their shoes,” he says. “We could start a business with the money the government will lend us. But we don’t really know how to manage a business." He's afraid the business will fail and the family will lose their home. How about a small business that does not need a big investment? A corner shop or a tea stall? “A tea stall is a great idea. People drink a lot of tea in Lucknow. But if they get to know our caste, we'll run into problems.”

There’s no easy escape out of this job, they all know that.

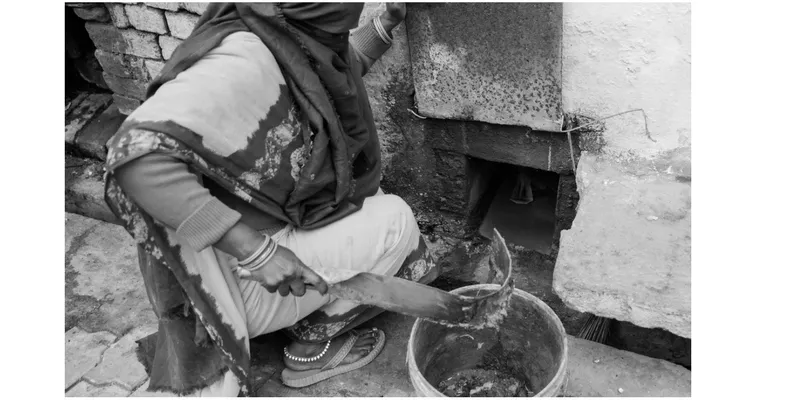

Vasumati takes us to her storage spot. A broom, a bucket, a U-shaped scooper, and a bamboo basket are stacked on top of one another. They are covered in dust and ash; it’s easier to empty the bucket with an ash layer because the contents don’t stick to it.

Her first stop is a house that we don’t even have to enter. There’s a hole covered with a metal sheet about three feet away from the entrance. She slides open the door and squats in front of the opening.

How much do the households pay, we ask, as Vasumati scoops the excreta into her bucket. “Rs 50 per person per month. Children who have not reached puberty and people over 60 years are not counted…Who can argue with them? These rules have been around for a long time.” She moves carefully, avoiding the water she is flushing into the gutter, then she straightens up.

She has to get going. She has 32 more toilets to clean today.

To view and download more images of different resolutions related to these stories, please visit Sharada's flickr album.

Disclaimer: The views expressed by the author are her own and do not necessarily reflect those of YourStory’s.