Meet the woman whose lifelong struggle laid the foundation for laws against sexual harassment in the workplace

In 1992 in the heartland of conservative Rajasthan, a woman fought against sexual assault openly, for the first time. This is the story of Bhanwari Devi.

The Vishaka Guidelines on sexual harassment has empowered millions of Indian women to work safely and given them the confidence to report any incident of sexual harassment in the workplace.

According to a report released by the Ministry of Women and Child Development, at least one case of sexual harassment in the workplace is reported every day in India, with a total of 1,971 cases reported since 2014.

This empowerment has been largely possible because of the struggles of one brave woman, Bhanwari Devi, who hails from a nondescript village in Rajasthan.

In 1992 she dared to speak out against some members of the upper-caste community who allegedly gang-raped her and also against her employers, who refused to take any responsibility.

Age may have wrinkled her face but her spirit, zest, courage, and hope is infectious. Dressed in a traditional Rajasthani lehenga, 57-year-old Bhanwari Devi, or Bhori Devi, as she likes to be called in her native language, stands tall.

It’s been 25 years, and her case is yet to see the light of day at the Rajasthan High Court. While justice may have been delayed, she is certain it won’t be denied.

She says: “We will get justice. My fight today is not for me. I am old, I will die; but my fight is for the future generation — for every girl, every daughter, who wants to pursue her passion free from the shackles of patriarchy.”

And therein lies the story of this feisty, determined woman who awaits justice so that others benefit from her fight.

Punished for doing her job

Bhanwari Devi was employed by the Rajasthan state government’s Women Development Programme in 1985. Her job was to fight against rampant child marriages in the state, not only by creating awareness but also reporting such incidents to the authorities.

She was involved in door-to-door campaigns and she would counsel women on hygiene, family planning, girl child education, while discouraging female foeticide, infanticide, dowry, and child marriage.

In 1992, she became aware of an impending marriage of a nine-month-old baby. Outraged, she wanted to counsel the family against such a decision. Even though the family belonged to the higher-caste Gujjar community, Bhanwari remained unshaken in her resolve. A child bride herself, married at the age of six, she knew the perils of a child marriage firsthand.

“I was just doing my job. She was a nine-month child and I had to stop it. I had to report it to the police. I spoke to the family and they refused to listen. I was abused and thrown out,” she recalls.

While she was aware of the possible consequences of a woman of lower caste, like herself, meddling in the affairs of a high-caste family, she chose to do her job. When a policeman intervened, he was told that Bhanwari was misinformed and that a family function, not marriage, was underway.

“The policeman came, ate sweets and left,” Bhanwari recalls.

The family got the baby married the next day and the following months proved to be torturous for them. Irked that a low-caste illiterate woman had dared to defy the social hierarchy, she was initially shunned by the village and ostracised by her community. And on September 22, 1992, Bhanwari was allegedly gang-raped by her high-caste neighbours in the presence of her husband.

“Five men from the family started beating me in the fields and they took turns to rape me. I can never forget that day,” says Bhanwari.

Following the incident, Bhanwari and her husband refused to remain silent. They approached the police and sought to file a report. The police initially refused to acknowledge the incident and instead questioned her whether she even knew what rape is.

Bhanwari remained firm in her statement and till date she has given her testimony eight times to various investigating agencies. She had to face insensitivity — from doctors, police officers, and even the judiciary.

Yet she went public with her rape and it has been 26 years since then. It was the first time a woman spoke about sexual assault openly in conservative Rajasthan. She was accused of lying; the Gujjar community denied the accusations. The village treated her as an outcaste, for rape is still a social stigma and Bhanwari’s case attempted to shake the established power structure.

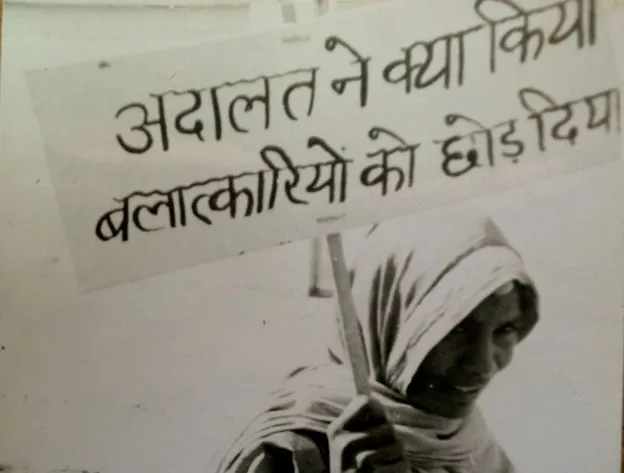

Despite this, she continued her pursuit of justice. Over the course of the trial, judges were inexplicably changed five times and, in November 1995, the accused were acquitted of rape.

The judge acquitted them citing several reasons:

- A village head cannot rape

- Men of different castes cannot participate in gang rape

- Older men of 60-70 years of age cannot commit rape

- A man cannot rape in front of a relative; in Bhori’s case, two of the accused belonged to the same family — the uncle and nephew

- A member of the higher caste cannot rape a lower-caste woman because of reasons of purity

Following the verdict, various NGOs and women’s groups came forward to help Bhanwari and the public outrage and protests forced the state government to challenge the verdict in the Rajasthan High Court. However, till date, only one hearing has taken place.

Yet, Bhanwari refuses to be cynical.

“I will continue fighting till my last breath. My fight is against the society where child marriages are still rampant despite being illegal. Law alone is not enough. Women, the whole society, need to support one another. Fight collectively against social evils.”

According to the last Census, between 2002 and 2011, 20 percent of the female population in India — 15.3 million girls — were married before they reached the age of 18.

All these marriages were against the law, violating the Prohibition of Child Marriage Act, 2006. In fact, Bhanwari Devi’s native state Rajasthan reported the highest number of child marriage cases.

Foundation for a new law

Bhanwari’s case shed light on the vulnerability of women in office spaces. Her employers, the state government authorities, refused to take responsibility for her assault as the incident had taken place in the fields.

“Ultimately, when you are working, who is responsible? In Bhanwari’s case the government and the panchayat said they are not responsible. So, when a woman is working for an employer, who should be responsible for her safety, her welfare?” Komal Srivastava, a volunteer from Bharat Gyan Vigyan Samiti questions.

She has been actively working with Bhanwari for the past two decades.

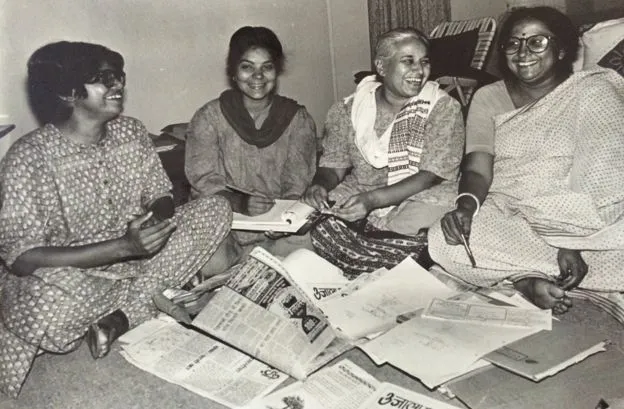

Activists and women groups across Jaipur and Delhi based NGOs raised this question and filed a public interest petition in the Supreme Court under the collective platform of Vishaka. They demanded that workplaces must be made safe for women and the employer must take responsibility for the employees, especially by focusing on women’s concerns and safety.

The movement eventually led to the definition of the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition, and Redressal) Act, 2013, usually known as the Vishaka guidelines.

Life remains at a standstill

Twenty-six years since her brutal gang-rape which shook the world, Bhanwari’s file sits in the pile of pending cases in the Rajasthan High Court, while she continues to live in the same village Bhateri, 30 km from Jaipur.

In all these years of fighting against child marriage in Rajasthan, assisting women in matters of domestic violence and rural craftsmanship, her life has witnessed little change since the 1992 incident. She still earns her livelihood by continuing to work as a saathin, a voluntary worker with the government of Rajasthan for the welfare of women and children.

“Our earnings are meagre with little financial support. In the village we do embroidery work, design work on dupattas and dresses. But there are no buyers, no business or ‘social startup’ to support us.”

Bhanwari is amused when I tell her that she has inspired a generation of women to not only gain acceptance but also work confidently in offices and corporates.

“If at all you find my story inspiring, don’t just stop there. Empowerment is not just about listening and knowing about injustice; it is also about speaking up and acting on it,” she explains.

Over the past years, she has been awarded by various organisations for her exceptional courage. The Delhi Commission for Women recognised her courage on March 8, 2017. In 1994, she was awarded the Neerja Bhanot Memorial Award.

Though she never got justice through the judicial system and the accused were acquitted, her case opened up a Pandora’s box of taboo topics into the public realm.

Bhanwari continues to fight for the rights of every girl in her village despite the threats to her life. She says,

“I am not afraid. What more can they do? I am not alone in my fight. The justice and the case is not just about me anymore. I am fighting for a society where there is gender equality; where there is no discrimination between two siblings of a household; where both brother and sister get equal rotis and education opportunities.”