Blitzscaling: success tips for hyper-growth from LinkedIn co-founder Reid Hoffman

This provocative book explains what you can learn from blitzscaling - the hyper-growth strategies of companies like Netflix, Amazon, Google, Alibaba, Tencent and Zara.

Digital technologies are adding capabilities of innovation, speed and scale never seen before, as explained in the new book, Blitzscaling: The Lightning-Fast Path to Building Massively Valuable Companies by Reid Hoffman and Chris Yeh.

Ace entrepreneur-investor Reid Hoffman has worn many hats as the founding board member and executive vice president of PayPal, the co-founder of LinkedIn, an angel investor in Facebook and Zynga, and a partner at venture capital firm Greylock Partners. He serves on the boards of Airbnb, Microsoft, and Kiva. He also hosts podcast series Masters of Scale and is the author of bestsellers The Start-Up of You (see my book review here) and The Alliance.

Chris Yeh is an entrepreneur, writer, and mentor. He graduated from Stanford University and Harvard Business School and co-authored The Alliance.

Their book draws on a class the authors taught at Stanford, as well as Reid’s podcast interviews with blitzscaling CEOs and founders. The material is spread across 325 pages and makes for an absorbing and insightful read.

When a startup reaches a stage where it has a fair chance at a killer product in a sizeable market, it can become a scale-up via blitzscaling, the authors begin. The Networked Age, with the global Internet and mobile broadband, has accelerated opportunities for blitzscaling around the world.

“In any business where scale really matters, getting in early and doing it fast can make the difference,” writes Bill Gates, in the foreword. “Prioritising speed over efficiency – even in the face of uncertainty – is especially important when your business model depends on having lots of members and getting feedback from them,” he adds.

The window for action can be tiny and can close quickly, and hesitation can lead to chasing or defeat rather than leading or victory. Other writers have also referred to the phenomenon as hyper-growth (particularly by hyper-funded companies). Blitzscaling is different from growth hacking and growth spurts.

Here are my key takeaways from the book, some of which are summarised in the three tables below. See also my reviews of the related books The Four, Big Bang Disruption, Connecting the Dots, The Culture Code, Multiplier, and The Moonshot Effect.

I. Foundations

“Blitzscaling is a strategy and set of techniques for driving and managing extremely rapid growth that prioritise speed over efficiency in an environment of uncertainty,” the authors define. It involves going from “zero to billion” rather than just “zero to one,” and has disrupted entire industries such as music, video, games, telephony and retail. It is not enough to have first-mover advantage, the first-scaler advantage is even more important.

Blitzscaling maximises speed and surprise and overwhelms competitors with the dizzying pace. It can be an offensive and defensive strategy and depends on positive feedback loops to build competitive advantage.

The concept of marketing blitz has already existed, for example, during movie launches, though the authors admit that the term ‘blitzscaling’ may have unfortunate connotations due to the German blitzkrieg during World War II.

Approaches to speed and efficiency differ with a degree of uncertainty, which the authors explain in a 2X2 matrix: startup growth (efficient growth in uncertain conditions), scaleup growth (efficient growth in conditions of certainty), fast-scaling (fast growth in conditions of certainty) and blitzscaling (fast growth in uncertain conditions). The stages of startup growth, blitzscaling, fast-scaling and scaleup growth constitute the classic ‘S-curve’ of market trajectories; these phases need to be repeated with each successive new product line.

The authors caution that the blitzscaling approach is counter-intuitive, risky, inefficient, unwieldy and even extreme. It should be used only if the prize is big and the competition is intense. Unfavourable consequences are a loss of market share and even embarrassing failure. There will be severe challenges to infrastructure, operations, customer service and management bandwidth.

The authors describe five phases of evolutionary growth of a startup: ‘family’ (less than 10 employees), ‘tribe’ (tens of employees), ‘village’ (hundreds of employees), ‘city’ (thousands of employees), and ‘nation’ (tens of thousands of employees). Each has different blitzscaling implications for the business model, strategy, management and culture.

II. Business Model Innovation

A business model describes how it generates financial returns by producing, selling and supporting its products, the authors explain. Technology triggers have led to digital channels and platforms supporting new kinds of business models. The challenge for innovators is that many of their business models are novel and unproven at first, and some ideas may even seem bad to investors.

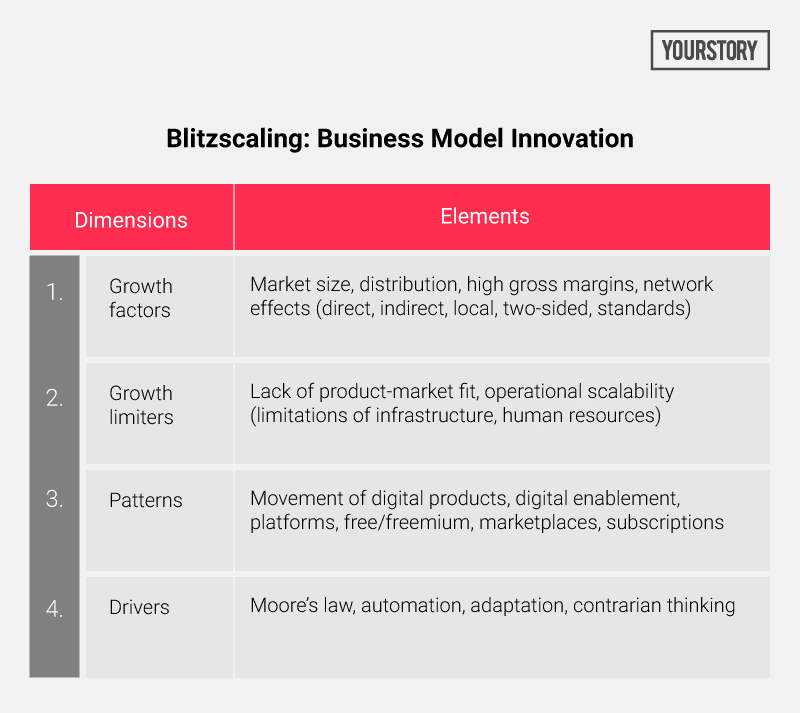

The authors describe four growth factors, two growth limiters, seven patterns, and four drivers of business model innovation for blitzscaling, which I have summarised in Table 1 below. The market size has to be attractive to justify an investment, with a good chance for a success path.

Distribution can be boosted via existing networks and viral effects. Virality can be purely organic or incentivised. Network effects drive growth and value creation; they produce and require aggressive growth.

Traditional business players struggle to find new business models, as seen in the case of Time-Warner’s earlier Pathfinder. New players also struggle to defend their business model, as seen in Netscape’s defeat by Microsoft’s Internet Explorer. AOL and Yahoo were early pioneers in consumer internet but were outflanked by Facebook and LinkedIn as social media. Craigslist and Wikipedia are influential but have not become massively financially valuable.

Business models can be extended to adjacent and new sectors, as shown by Amazon’s move from ‘Earth’s Biggest Bookstore’ to ‘The Everything Store’ – it also used its infrastructure experience to launch AWS. Amazon has had its share of failures as well, such as the Fire Phone.

Alibaba and Airbnb blitzscaled their two-sided marketplace models. SalesForce.com used the subscription and SaaS model to disrupt enterprise software and reach out to SMEs as well. YouTube is a classic example of two-sided network effects. Many startups have launched via Google and Facebook platforms, but changes in their rules later affected companies like Zynga and Demand Media.

PayPal leveraged eBay as a distribution channel by offering the feature ‘Pay with PayPal,’ and Airbnb tapped Craigslist for its growth. DropBox incentivised virality by offering extra storage space as referral rewards; it also used the freemium model to increase the number of customers as well as revenue.

Netflix anticipated the effects of Moore’s Law and bided its time; it first launched DVD rentals using a subscription model and waited for years before streaming video became feasible and viable. Netflix exploited its direct subscription model and consumer intelligence to outflank traditional TV networks with their thematic channel-based models.

LinkedIn used growth hacking tools like email address book importing to build its user base, then discovered that companies were willing to pay to locate job candidates. This led to the launch and scale of the enterprise subscription product, as LinkedIn displaced the traditional resume.

Google has leveraged its formidable ad revenues to support new products such as Android and Chrome. But it also had its shares of failures, such as Buzz, Wave and Glass. Google has multiple parallel projects, whereas Apple prefers small product lines and a few major products.

Facebook started off by targeting only college students before scaling up. Sponsored posts in newsfeeds have become a money-spinner, and the company has invested heavily in top executives. Its early motto of “Move fast and break things” has been changed to “Move fast and break things with stable infrastructure.” However, there have been serious challenges as well with issues like inappropriate content and political manipulation.

III. Strategy Innovation

Strategic decisions focus on what to do as well as what not to do. Some sectors and companies are not suited for blitzscaling, such as world-class fine-dining, the authors explain.

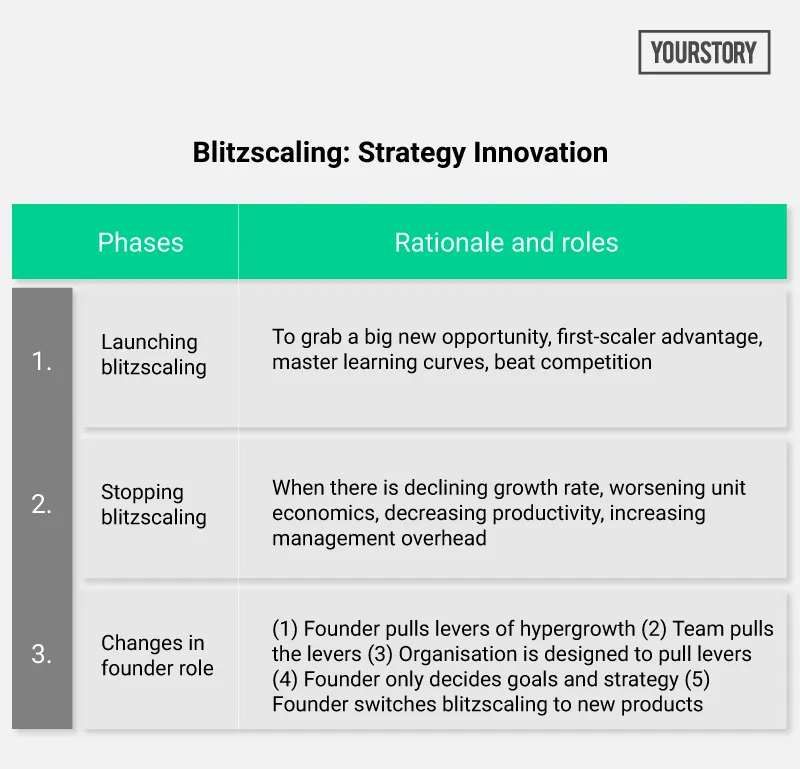

Blitzscaling involves rapid guesstimates (instead of careful planning), inefficient capital expenditure (not cautious investment), and ignoring angry customers (not courteous service), the authors caution. Companies need to be clear about when to launch and stop blitzscaling, and how the founder role changes with the size of the company; I have summarised some of these considerations in Table 2 below.

Though the Chinese e-commerce market was negligible when Alibaba was founded in 1999, the Chinese middle class was poised for growth. Massive fundraising and blitzscaling have helped Alibaba attain 80 percent market share in China today.

Blitzscaling helped Netflix master the steep learning curves in digital content distribution and creation, which has become a competitive advantage. Netflix first mastered DVD licensing and distribution and developed new features like recommendation services. It then had to learn how to master rollout of streaming infrastructure, and finally content creation in the face of competitors who had a century of media experience.

Airbnb had to resort to blitzscaling to tackle competition in Europe from the clone Wimdu, launched by Germany’s Rocket Internet; it expanded in several new countries at the same time. To grow fast, ClassPass founder Payal Kadakia hired new talent from her team’s personal networks, rather than through recruiters and interviews.

Tumblr was not able to blitzscale the way Twitter did and was acquired by Yahoo. Nokia was not able to survive the blitzscaling assault of Apple and Google’s Android. Groupon is an example of when to stop blitzscaling; its overheated growth ran into problems when businesses discovered that deals did not necessarily lead to long-term business.

IV. Management Innovation

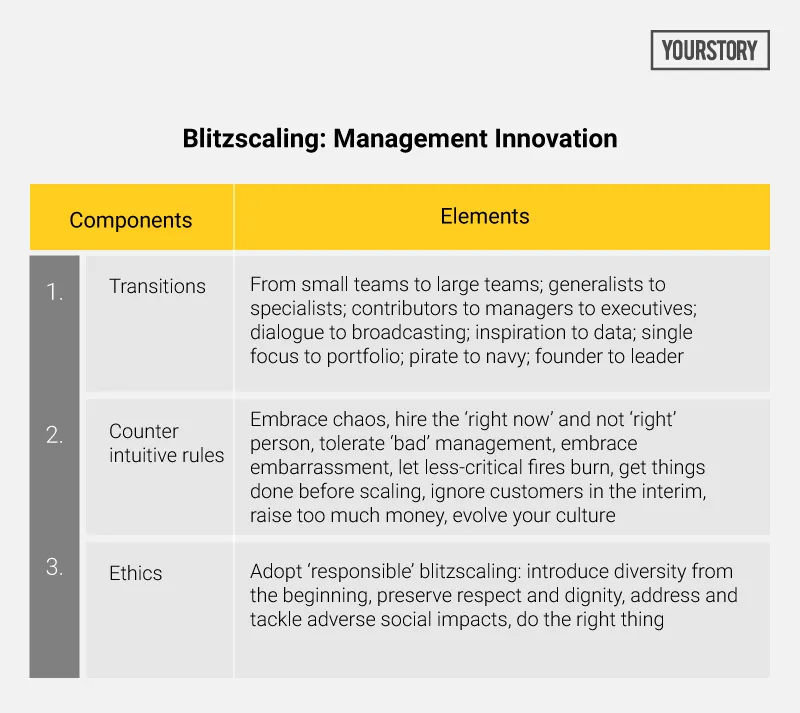

Many companies flame out or implode while scaling, and the authors offer insights and examples of the transitions that companies struggle with, and the rules and ethics they need to follow. I have summarised some of these elements in Table 3 below.

Flexibility, fast decision making and coordination are the advantages of small teams. For example, PayPal pivoted four times from different platforms and devices within just its first year. However, people who are smart and effective at early stages are not necessarily successful at scaling stages.

“Smart and scrappy” generalists are useful in early stages but there are limits to organic learning in scaling phases; outside specialists are needed later for functions like HR. There are also risks that there may be “transplant rejection” due to lack of culture fit. A mix of generalists and specialists is usually needed, and generalists can move on to new roles, or leave the company but remain engaged via an alumni network.

The organisation’s “collective learning rate” determines its ability to anticipate and harness future trends. In startups that become really large, outside executives will need to be brought in to lead managers, because the mentoring and expertise needed were not present organically at earlier stages, eg. VP engineering. Design marketplace Minted brought in a VP Finance from the outside.

As a startup grows, elements of broadcast communication will be needed between the founder and employees, via email or video. For example, Brian Chesky of Airbnb sends a long email to all employees each Sunday night. YouTube’s Shishir Mehrotra also sends weekly emails. Marc Pincus of Zynga holds Monday morning coffee talks with all new employees of that week.

Decisions will need to be based on gut feel in early stages but increasingly on data in later stages. Selina Tobaccowala of SurveyMonkey developed a handful of key metrics such as free users, paid users and engagement level; YouTube’s Shishir picked the metric of watch time.

Early stage time horizons may be a month ahead, whereas larger firms plan years ahead. Page views are a vanity metric for tech startups, but a key metric for a media company. Dashboards help give daily views of the health of the company.

A mix of qualitative and quantitative analysis will be needed. Some say that Google prefers data-driven design, while Apple prefers genius-driven design; both approaches need to complement one another.

Companies also need to adopt “multi-threading” or a combination of exploiting (mature products) and exploring (testing new products). LinkedIn had a “mishmash of revenue streams,” such as job listing fees and enterprise licensing. The product leaders worked independently but were also aligned with one another.

The authors offer the interesting maritime metaphor to describe early-stage startups (rebellious pirates), established companies (disciplined navy), captains (market heads) and admirals (global heads). For example, Steve Jobs kept the early Macintosh team separate from Apple (pirates), Salesforce tapped the broader ecosystem of developers for AppExchange (navy), and Uber brought in Dara Khosrowshahi to fix elements of its toxic culture (admiral).

Founders should scale themselves up via delegation, roping in an executive assistant, and increasing their learning abilities. “You have to make yourself into a learning machine,” the authors urge; this can be done via voracious reading, roping in mentors and experts, connecting with peer founders, and creating a “personal board of advisors.”

“The most successful scale-ups are those that have managed to keep the promise of being small while reaping the benefits of being big,” the authors explain. “The failure to build a unified executive team is sadly common,” they caution.

In the chaos of blitzscaling, teams need to be comfortable with uncertainty and tackle multiple roles. People should be hired based on the ability to solve problems immediately, even if they are not the perfect fit. Job titles should not be fought over. Salespeople need to be aggressive yet adaptable.

For example, PayPal’s Jamie Templeton shifted from product to engineering to systems to policy. LinkedIn launched with basic MVP features; only then did they bring in Minna King to help in the early stages of taking the product global.

“Entrepreneurs have to walk a fine line between fixable and fatal flaws,” the authors caution. A free consumer product can get away with most flaws, whereas a free enterprise product needs to be more refined.

There is a difference between what users say and do (predicted and observed behaviour), and this should be factored while analysing feedback and log files. Friends and family don’t necessarily give criticism in their feedback. Many focus groups said photo tagging on Facebook was creepy, but after launch, it experienced wide engagement.

In blitzscaling stage, not all fires can be put out. In decreasing order of priority, the firefighting focus should be on distribution, product, revenue model, operations and competition. SurveyMonkey decided to postpone the design of its product because even the ugly version had good engagement.

To handle the photography needs of renters, Airbnb founders took the photos themselves and then hired photographers. The next step was to get an intern to manage them and then develop a spreadsheet to track this work. Eventually, the spreadsheets were thrown away for a new system.

In its hypergrowth stage, PayPal was raising capital, competing with other products, and negotiating a merger – it simply ignored customer complaints during this period. Luckily, they also raised enough financing just before the market meltdown in 2000. The value of additional funding during blitzscaling can outweigh the potential negatives of equity dilution, the authors explain.

At all stages, company culture should be clearly articulated, understood and followed. Southwest Airlines lives its messages of “servant’s heart,” “warrior spirit” and “fun-loving attitude.” HP founders defined the HP Way on foundations of engineering culture, whereas Oracle and Cisco have more of a sales-oriented culture.

At early stages, startup culture spreads from the founders via osmosis. As it grows, new employees need to recreate the culture. More process and reinforcement need to be added at later stages. “It’s not always easy to move from organic to deliberate cultural transmission,” the authors say.

Values interviews help ensure that you are hiring “missionaries not mercenaries” during scale stage. HR plays an important role in how employees are managed, evaluated and rewarded. Diversity in the workforce helps avoid groupthink, bias, and stagnation. In larger organisations, experts in government policy will also be needed.

Airbnb reinforces its verbal messages with visual impact: its conference rooms are replicas of rooms on rent, so employees are always reminded of how their guests feel. Netflix has a Culture Deck of slides explaining its high-performance culture; the slides are revised regularly.

V. The road ahead

Blitzscaling has helped companies go from “garage to global dominance.” It has extended to companies in sectors beyond digital technology as well. Chesapeake Energy moved rapidly to negotiate mineral rights leases with landowners in the shale oil industry.

Zara leverages automated factories and 300 small shops in Spain and Portugal, and takes design inputs right from stores - rather than outsource manufacturing to a country like China. Products are distributed in small batches rather than large shipments. Together, the labour and shipping costs may be higher, but the gain is speed and flexibility (only two weeks for design and delivery; 10,000 new designs a year; lower overstock).

Large companies, and not just startups, can also tap blitzscaling. They have the advantages of scale, brand, longevity, and acquisition power, as in the case of Priceline’s acquisition of Booking.com. But they also face challenges in shareholder opposition to risky bets and managerial overhead that restricts agility. Large companies can overcome these challenges by reinforcing a startup mindset, eg. Jeff Bezos calling every day as Day 1.

As far as regions of the world go, Silicon Valley and China lead in blitzscaling thanks to a seasoned pool of executives from hyper-growth companies, large markets, and hungry investors. Other scale-up clusters include Seattle (Microsoft, Amazon), Los Angeles (Snap, SpaceX, Dollar Shave Club), New York (Rent the Runway, Birchbox), Estonia (Skype), Stockholm (Spotify), Kenya (m-Pesa), Australia (Atlassian), and India (Flipkart).

Blitzscaling elements can also be seen in the political, social, educational, and health sector, eg. Obama’s election campaign, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation tackling malaria on a global scale, Khan Academy, and Charity Water.

The book ends with a discussion on “responsible blitzscaling,” addressing issues of ethics, regulation, and the overall public good. Related ethical concerns have arisen with the dawn of each new technology wave, right from the days of the written word, printing press, newspapers and television.

New disruptive trends to watch include AI, self-driving cars, blockchain, VR and gene editing. Multiple platforms and technologies are also converging, leading to new opportunities and complexities. This calls for everyone to be an infinite learner and first responder, and yet try to stay calm and stable.

In sum, blitzscaling is useful for startups and innovative enterprises. Even for others, it helps to understand how today’s dominant tech players got to their current status, and how this affects broader society. Ultimately, blitzscalers will impact our talent pools, neighbourhoods and governance.

Responsible blitzscaling can change the world for the better. “Competition may be challenging for the individual person or company, but it is good for the collective whole,” the authors sign off.