From inspiration to influence: how to harness storytelling for business success

Mondays are good days for reflecting on the outstanding stories of the past week, and not just the interesting data. Storytelling, listening and triggering are a core competency for a business, as this book explains.

Listening to stories and telling them comes naturally to people, and deserves a systematic process in today’s businesses as well. Putting Stories to Work: Mastering Business Storytelling by Shawn Callahan is a practical guide based on two decades of work in storytelling in companies across dozens of countries.

The 11 chapters are spread across 270 pages, and make for an informative read. There is also a five-page story index which effectively illustrates the principles of story tagging and taxonomy.

Shawn Callahan is a storytelling author, trainer, and coach. Based in Melbourne, he has worked with companies ranging from Danone and Allianz to SAP and Tesco. He is the founder of Anecdote, whose consulting programmes are delivered in eight languages. Shawn holds a bachelor’s degree in geography and archaeology from the Australian National University.

“Smart organisations are investing in helping their people to systematically and purposefully find and share effective stories,” Shawn begins. In the worlds of film executive Peter Guber: “Storytelling is not show business. It’s good business.”

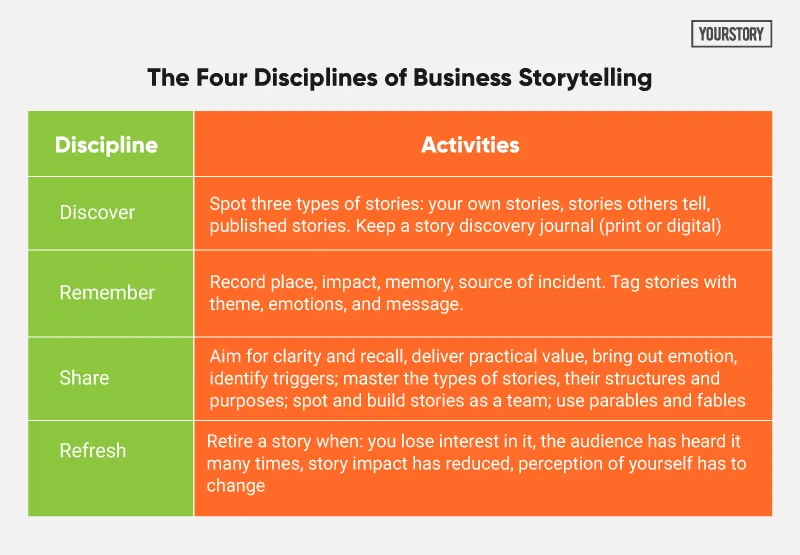

I have summarised my key takeaways in the three sections below, as well as in Tables 1 and 2. See also my reviews of the related books Unleash the Power of Storytelling, Let the Story Do the Work, The Storyteller’s Secret, Whoever Tells the Best Story Wins, Stories for Work, and Stories at Work. Entrepreneurs should check out YourStory’s Changemaker Story Canvas, a free visualisation tool for startups and innovators.

I. Foundations

Storytelling via miming and drawing predates the spoken word. “Writing now dominates corporate life. Yet, at our core, our innate communication skills are miming and oral storytelling,” Shawn explains.

He cites the definition of ‘story’ by Richard Maxwell and Bob Dickman: “Stories are data, wrapped in context, and delivered with meaning.” Shawn adds: “Stories are a user manual for life.”

A business story has a time and place marker, a sequence of connected events, dialogue, and a business point. A good story conveys description, visualisation, and empathy. It should have an element of surprise, and depth in its characters.

Stories in business contexts are unfortunately dismissed by many leaders because stories are perceived as a waste of time, not business-like, something which only children or entertainers do, a way of manipulation, or are made up. Instead, Shawn calls for leaders to take the right attitude and actions towards effective storytelling.

“Sharing real-life oral stories bestows on a leader the superpowers of memorability, meaningfulness, and emotionality, all of which are essential in a business world where relationships, trust, and the ability to adapt have become crucial capabilities,’ Shawn emphasises.

1552897270850.png?fm=png&auto=format)

The book focuses extensively on oral storytelling and opens the door to more research on written stories and digital media. Storytelling in the business context is like “corporate anthropology,” and making it a regular productive habit calls for motivation, skills, and a diverse repertoire of durable stories.

Deliberate practice, mindful development, and a focus on the human element are key for storytelling. Having a “story buddy” or trusted inner circle helps test stories in this regard. Stories can be classified into three types on the intimacy spectrum: front porch stories (for everyone), kitchen stories (for the inner circle), and bedroom stories (the most intimate ones). Practice helps determine how much of oneself the story should reveal.

Powerpoint presentations and CEO roadshows are not as effective for communicating business strategy as a memorable story with an overarching narrative. By answering the Why question, such stories help the strategy to be remembered by employees and retold to others (even with their own additions woven in).

Engaged employees will go above and beyond their call of duty; it helps if leaders share stories about the organisation’s purpose, progress, and organisational trust. It is important for leaders to also trigger and hear stories from their employees - this helps understand perceptions and commitment.

“Stories of remarkable efforts are great fuel for inspiration,” Shawn explains. For example, based on customer feedback, Apple asks employees to share stories about how they effectively served customers each day. “To inspire at work, leaders must share stories of events big and small,” he advises.

Experiences framed by a series of stories reinforce better decision-making practices. Relevant lessons learnt can be shared by stories and drive behaviour change. Truly engaging stories not only draw listeners in, but increase empathy and even lead to prediction of what happens next.

Story listening helps unearth half-truths, misinformation and lies (‘anti-stories’) in the corporate grapevine and need to be countered not just with facts but better alternative stories or replacement stories.

II. Story mastery

To be a successful storyteller requires separating stories from non-stories (opinions, facts, timelines), having stories in your “mental back-pocket,” narrating anecdotes and broader patterns in the company, and having a diverse range of fresh stories (see my summary in Table 2 below).

“Spotting stories is the fundamental narrative intelligence you need to become a business storyteller,” Shawn emphasises. This involves drawing connections between lived experience and business ideas, and includes identifying “rough diamonds” that can be polished to become good stories.

In the entertainment industry, stories of power, death, children’s safety, and sex make for “sticky stories” that strike a chord with our reptilian brains. Movie scenes and ads offer good story elements.

In the business world, stories can be spotted where periodic meetings are taking place, during crises, when people are under pressure, or where new things are happening. They can even be spotted wherever the “quirky, eccentric mavericks hang out.”

Story-eliciting questions are useful in this regard. Artworks, images, and photographs, especially of people in action, can be evocative tools as well; so are artifacts such as sketches, maps and other physical objects. However, stories need not be over-dramatised or made into performances; the best communicators are conversational, Shawn explains.

Stories can help leaders show that they care, have character and purpose, and have learnt lessons from their experience. For such stories to be memorable, they have to be visual, emotional and interesting, Shawn advises.

Stories can be remembered via effective tags, with many examples illustrated in the book: CEO rejects bribe, The lawyer with integrity, Shifting the factory, The Xerox repairman story, Refugees demanding a library card, The Zen master and the professor, and The Apollo 13 scene.

Rather than relying only on big stories, it helps to tell a lot of small but vivid, relatable and emotional stories. At the same time, telling stories all the time without a business point risks making the narrator sound like a “gasbag,” Shawn cautions.

Stories help ideas spread like a virus (Malcolm Gladwell) or even a forest fire (Duncan Watts). Founder stories are particularly powerful in reinforcing the company’s origin, early struggles, hard choices, core values, and changes in direction. For example, when Steve Jobs returned to Apple, he trimmed down the focus to only four products in a 2X2 matrix (Consumer and Pro; Desktop and Laptop).

“A value is not a value until it costs you money,” Shawn explains; values stories should illustrate the tradeoffs made during decisions, and make values like honesty and integrity come real.

Vision stories should build on desired futures, and have phrases like What if. Connection stories establish rapport through the human element, particularly when addressing new audiences; they build on turning points in personal events or work occurrences.

Clarity stories strengthen logical reasoning through narrative structures like <In the past> <Then something happened> <So now> <In the future>. It acknowledges past problems and the complexities of change, and then describes desired states and steps.

Imagery and elements of contrast are important in clarity stories. Involving a team in developing clarity stories helps make them all attached to it (the ‘IKEA effect’ of loving something you create).

A strategy story must not come across as too smooth or slick (a ‘Pollyanna story’ where everything is good). It should acknowledge earlier anti-stories, and the leaders’ behaviours should be aligned with the story.

Influence stories can use the ‘story before argument’ principle to help overcome confirmation bias in listeners; they should not feel opinions are being pushed at them. The structure should be <Acknowledge the anti-story> <Share the new example or story> <Make the case> <Reiterate the point>.

In other words, the influence pattern has a negative story followed by a positive story, which together offer the solution. The influence story must be true, relatable, credible, simple, and verified.

“Anti-stories reflect the true concerns of employees and they must be addressed. Consequently, it’s vital that leaders know about the anti-stories in their organisation. They need to be connected to their workforce, have their ears to the ground,” Shawn emphasises.

Case studies can be livened up with human elements such as emotions and names of people involved (even if the names used are not the actual names). Analogy stories bring in symbols from other fields (eg. Ryan Lochte beating Michael Phelps by inventing a new kind of dolphin kick), or from parables (eg. bringing Zen stories into Western culture).

Presentations can be simplified by structuring them into three sections: What, So what, Now what. Sales pitches can draw on the clarity story pattern, and even include failure stories and lessons learned; clients should also be invited to share their own stories.

III. Stories in action

The book is packed with a number of personal and business stories, drawn from Shawn’s extensive experience. Narrative intelligence in a company changes the culture for the better.

For example, the Victoria Department of Education has monthly teleconferences where teachers share stories of innovative practices, and discuss how to replicate and scale them. Ritz-Carlton asks employees to submit ‘Wow’ stories of great customer service every two weeks; and the HR department selects one for sharing across the hotel chain.

Wynn Resorts has established a story programme that runs every day. In groups of 6-12, employees are asked each day to share stories of something special that happened with guests. This makes successful employees feel like heroes, and spurs them to be exemplary and develop their own stories as well.

Home appliances company PIRCH has developed a manifesto of 23 aphorisms such as Honour your promises, Be real, Slow down, and even You have a great bottle of wine, drink it. Its showroom is like an amusement park for adults, where they can “nude up” and walk under a 15-metre row of showerheads to decide which one to choose.

New employees are exposed to good customer practices and storytelling in companies such as Nordstrom, Tesla, Tiffany, and Lululemon. They then form a circle to share stories about the company’s aphorisms based on a collection of artifacts. Informal sharing of stories also happens around beach bonfires, where founder stories and local leader stories are narrated. Exemplary workplace stories are shared each week on the intranet, and are called Manifesto Moments Online.

The book ends with a maturity framework of storytelling excellence, and tips on ethical guidelines. In sum, the material is useful, insightful, compelling, and even fun to read, and provides a wealth of resources for those wishing to master business storytelling.

Also read: Focus on the customer task, not just product feature: 3 innovation tips for entrepreneurs