Coronavirus crisis will change consumer behaviour forever: Kallol Banerjee of Rebel Foods

Kallol Banerjee, Co-founder of Rebel Foods, reveals how the coronavirus pandemic has hit India’s QSR industry, why cloud kitchens remain relevant, and why founders must focus on standardisation and processes to scale.

The coronavirus pandemic has brought India’s expanding food and beverage industry to a grinding halt. The nationwide lockdown has driven footfalls down to zero and sent revenues into free fall, with restaurateurs struggling to maintain fixed overheads and other expenses.

The restaurant industry is one of the largest employers in India, engaging close to 10 million people and second only to the railways, according to National Restaurant Association of India.

But, as of now, COVID-19 seems to be pushing restaurants and cloud kitchens to the point of no return, with many restaurants not likely to survive beyond three months.

The bloodbath has already started. On May 1, Mumbai-based celebrity chef and entrepreneur Pooja Dhingra announced that she was shutting down her iconic Le 15 Patisserie + Cafe in Colaba in the wake of coronavirus.

Many others are likely to follow suit, in metros and across Tier II and III India.

In the midst of this unprecedented downturn, YourStory caught up with Kallol Banerjee, Co-founder of Rebel Foods. Founded in 2011, the foodtech startup now runs 11 brands, 300 cloud kitchens, and 2,200 internet restaurants, including brands such as Faasos, Behrouz Biryani, Oven Story, and Mandarin Oak.

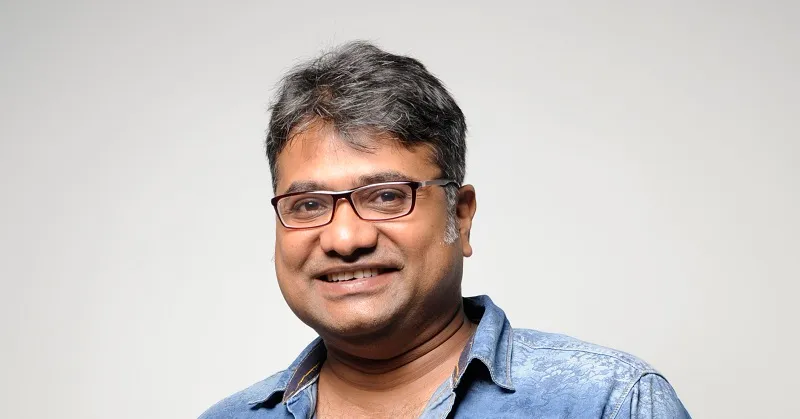

Kallol Banerjee, co-founder of Rebel Foods

Rebel Foods is disrupting the food delivery business by building and running the largest chain of internet restaurants across the world.

In the time of coronavirus, Kallol believes that the company will continue to be an operating system for its food brands, which can scale to 1,000 restaurants in under a year using the internet, by ensuring standardisation and processes.

Edited excerpts of the interview:

YS: The pandemic has hit everyone hard. How is Rebel Foods navigating the coronavirus crisis?

KB: We are not able to operate all our kitchens, and the problem is three-fold.

People do not want kitchens to operate at neighbourhood level. Second, the government has not allowed many kitchens to operate. Finally, there is no public transport for our staff to travel. We have close to 317 cloud kitchens, of which only 175 or 200 are operational. We are trying to get as many kitchens open as possible.

Ours is a multi-brand operation, and we need a certain number of people operating those kitchens or brands. In kitchens, where we can do a full shift we continue to do so with full staff. There is no point operating a kitchen with two people; in such cases, we have shut operations

.

We have worked to optimise the workforce, based on the nearest kitchen. This has helped as the staff closest to a kitchen can work there.

On the demand side, we have seen volumes drop by 40 percent. However, the brand sales are growing on a like-to-like basis. People who are still ordering are opting for places they trust and we are lucky to have them choose us. We have taken measures such as sharing body temperatures of delivery persons (on invoices) and tracking food preparation through CCTV cameras.

YS: Blue-collar workers have all gone home. How has this affected business? What about your suppliers?

KB: We took a decision at the end of March to save jobs and change salary structures, based on slabs. We want to ensure a 24-month runaway, which is why we asked people to take salary cuts. Surprisingly, many of them were okay with the cuts. My co-founder, Jaydeep Barman, and I are not taking salaries.

We are a 4,500-people operation, and on an average have 15 to 20 people with each brand. Most of these workers are not locals and luckily not many have left us. We have ensured that our staff have rooms near kitchens, but the real problem is local travel. It has been a mixed bag.

The situation is better on the food supplies side. We work with delivery partners; if they are not able to deliver, our algorithm tells us that we have to complete the delivery. This algorithm kicks in when customers order from .

We have had to remove some SKUs as we don’t have the ingredients. We stopped a few brands during the pandemic-led lockdown. For others, we connected with logistics partners and made sure stock was available.

I think things will improve on the supply chain front as essentials are already being transported.

In the future, there will be a complete shift in consumer behaviour as people’s concerns will not vanish.

Delivery will remain important as people won’t eat out much. But while opting for dining in, consumers will want assurance, they will want to know where ingredients are coming from. We will enable our customers to know every detail of the food they have ordered.

YS: With zero marketing spend, how are you managing your brands and your constant need to experiment?

KB: There is no marketing spend on content that focuses on taste and flavours now. Trust is what people care about right now. We have put in place many features –taking people’s temperature, tracking food preparation, and 24/7 CCTV monitoring of kitchen hygiene.

We are delivering masks with every Faasos order instead of a free dessert. We are constantly experimenting, and are working on called the 500-Calorie Project, a pilot in Mumbai, where we work with nutritionists to create options for those focused on a diet.

This is a great time to work and test new brands. We try a concept for six months and make sure there is a product-market fit.

All our internet stores have their own ordering app. If you want to build a demand channel, we cannot do the job of aggregators like Zomato and .We want to go after small opportunities within that demand. Seventy percent of our demand comes from third-party aggregators.

YS: What does a cloud kitchen mean to you? Tell us about the business of brands in a cloud kitchen.

KB: Cloud kitchens mean different things to different people. The concept essentially translates into a huge kitchen that you let out to restaurants.

Our model is not to look at cooking stations by brands, but by processes. It’s common knowledge that there is no real estate cost to cloud kitchens, but we pay commissions to aggregators for deliveries.

There were no brands when we started in India. Compare this to the US, with over 600 chains. This was the first problem that we tackled.We soon realised that if you can make food consistently and safely across kitchens…that is the play for scale.

Say I launch a burger brand. I can promote it for a while, and study how people like the taste and consistency. With this learning, I can launch the same processes across India overnight and make it a chain as large as a western brand.

The only difference is that we are not operating any physical restaurant. I can then create three variations of the same burger brand, price them differently, and launch sub brands in the market. Now I have 900 restaurants.I can discount with one burger brand,and keep it premium with the next burger brand. This approach has ensured we are flooded with inquiries to work with us.

Most big hotels want to give us their kitchens as they are empty through the day. What we have developed is an operating system to build digital brands where we can scale up and down as and when we want.

We can create as many brands as we want. That’s why we are global; currently we are in Dubai and Indonesia. We believe social distancing will make brands such as ours more popular.

YS: You have been mentoring a few brands recently. Do you have any advice for aspiring founders?

KB: We mentor Bengaluru-based coffee brand Slay and have opened our network to the founder. This is a thesis where we don’t have to do everything ourselves. It is an interesting play in India where you don’t get good coffee; we want to use the internet to deliver good coffee drinking experiences.

We will in the future mentor brands for the scale that they can bring across locations with standardisation of processes. Our SOPs are such that no one has to taste every meal and okay it.

On a day-to-day basis, standardisation is the hardest thing for any brand. You have to audit consistency every day, and that’s why we have been able to scale.

If an entrepreneur is able to handle 300 kitchens in the same way,s/he has made it. An entrepreneur needs clarity and mental design to scale the business.

When we started, we wanted to build an Indian QSR brand and realised that Indian cooking was not standardised to scale like western brands with the so-called freezer-to-fryer model. We did not start out thinking we would be a big cloud kitchens company.

Being into cloud kitchens does not guarantee funding. What do VCs want? They want people who can build big businesses with a great team and processes. We were trying to solve a problem and that’s the reason all our investors have stayed with us through this journey.

(Edited by Teja Lele Desai)