Retaining critical knowledge – how to ensure business continuity during times of layoff and churn

This useful book provides frameworks and examples of how businesses are ensuring knowledge retention when key personnel are departing.

When highly-skilled experts, engineers, and managers leave their organisations, they take with them years of hard-earned, experience-based knowledge. Though a competitive advantage, such knowledge is often undocumented, and losing it leads to serious setbacks during layoffs, retirement, departures, M&A activity, and transfers.

Frameworks, checklists, tools, and case studies of core knowledge retention are well explained in the book, Critical Knowledge Transfer: Tools for Managing Your Company's Deep Smarts, by Dorothy Leonard, Walter Swap, and Gavin Barton.

The book is useful for business leaders, knowledge management professionals, talent experts, HR heads, and individuals who want to ensure a lasting legacy when they leave. The nine chapters are spread across 220 pages, and make for a useful and informative read.

Dorothy Leonard is a professor at Harvard Business School and chief adviser of the consulting firm Leonard-Barton Group. Her other books are Deep Smarts, When Sparks Fly, and Wellsprings of Knowledge. Walter Swap is professor of psychology at Tufts University, and Gavin Barton is managing director of the Leonard-Barton Group.

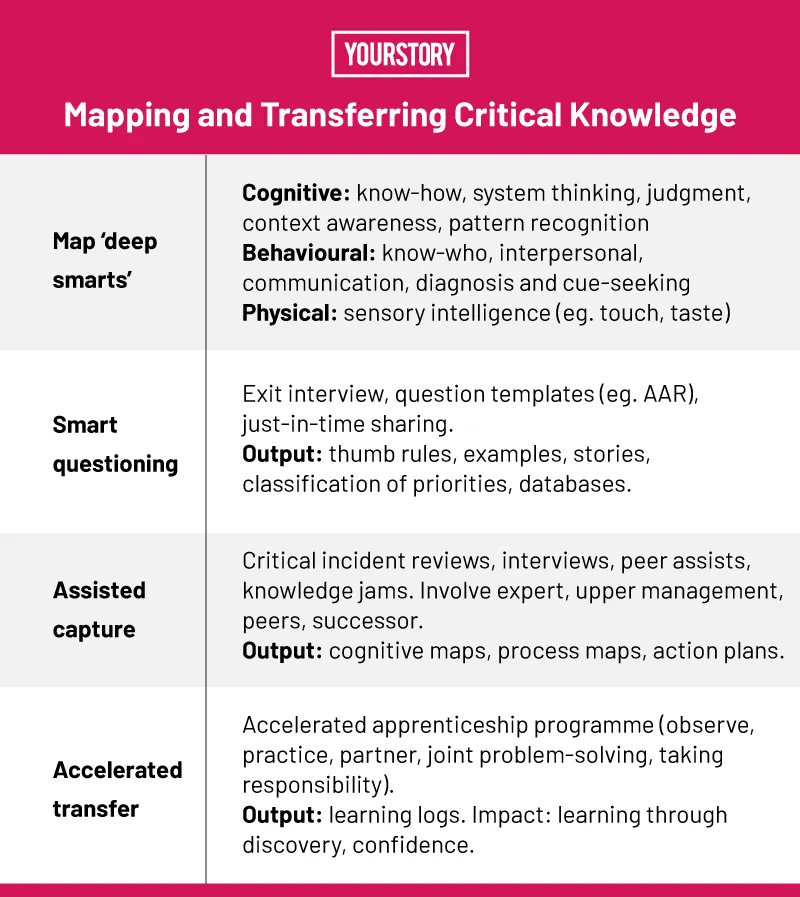

Here are my takeaways from the book in the four sections below, and summarised in Table 1 as well. See also my write-ups on the CII India Knowledge Summit, and reviews of the related books What you do is who you are, Multipliers, The Culture Code, Trillion Dollar Coach, and The Moonshot Effect.

Types of knowledge

Knowledge is a powerful asset in organisations for innovation, productivity, and risk management. It is crucial for firms to systematically create, capture, preserve, share, use, and re-use organisational knowledge assets, the authors explain.

The authors refer to the organisation’s critical, experience-based knowledge as ‘deep smarts’. It is a combination of cognitive, behaviourial and even physical knowledge and skills. Some of it is manifested in explicit form (eg. articles), but much of it is implicit (embedded in processes) and tacit (unconscious, hard to articulate).

Some of the knowledge is technical, some managerial, and some both. Smarts are able to create actionable steps in the face of complex and unclear situations, and shift between strategic and tactical perspectives.

Such knowledge is important in decision-making, judgment, industry interactions, and government consultations. It is not necessary to ‘clone’ experts, but important to capture the business-critical core of their experience-based knowledge, the authors emphasise. This includes their encyclopaedic memory, professional networks, and intimate customer knowledge.

While new waves of employees bring in fresh perspectives and creative ideas, it is also important to preserve vital knowledge of the past. This helps business continuity and avoids reinventing the wheel.

Knowledge communities and teams

Knowledge transfer works well if the company already has explicit processes, culture and tools for knowledge sharing and emergence. Effective knowledge sharing entails trust, willingness to share and learn, training, mentoring, job rotation, communities of practice, and effective tools. Knowledge sharing should be embedded in the job, and supported at all levels.

Enablers for knowledge flow include intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Intrinsic motivation comes from a desire to make a contribution or the sheer joy of teaching and mentoring. Extrinsic motivation can be provided in the form of recognition, awards, rewards and even pressure.

Despite biases, quirks, agendas, and even political motives, it is important for organisations to come to agreement on their critical knowledge areas and how to strengthen them. The authors recommend that teams to conduct these activities at various levels should include the experts themselves, upper management, sponsors, facilitators, coaches, peers, and successors.

In organisations with workforces of different generations, “reverse mentoring” helps younger experts tutor their seniors in areas like the use of digital tools. Youth today have high levels of confidence, desire flexible work schedules, and are impatient to get ahead.

Youth prefer researching online before asking advice from experienced employees, the authors observe. To deal with such contexts, companies must socialise knowledge flows through rich storytelling, digital media like videos, crowdsourcing, open innovation, and social media.

Transferring critical knowledge

Depending on how much time there is to transfer knowledge and how critical it is, the authors recommend a range of techniques beyond just asking experts to give lectures or talks. Smart questioning is good for quickly gathering explicit knowledge, but apprenticeship and mentoring are effective over longer periods of time for tacit knowledge.

Knowledge maps go beyond job descriptions to capture key tasks, components, and interactions. “Questioning is an art, sharpened through experience,” the authors emphasise. Some techniques can be based on templates and do not require much training.

Exit interviews can be led by a panel of experts, successors, peers, and managers. Good questions should probe into key learnings, problems overcome, challenges remaining, outstanding achievements, and examples for each rule or principle.

The After Action Review (AAR) template covers what was supposed to happen, what actually happened, why differences arose, and how to improve next time. Outputs can be in wiki-like formats for knowledge growth in fluid fields.

Assisted knowledge capture involves outside facilitators and coaches, who bring in the advantage of an external perspective relatively free of organisational biases. They also don’t hesitate to ask “dumb questions”, the authors joke.

This approach involves probing to unearth critical thinking of experts during key incidents. Detailed walkthroughs are needed to capture experiences from such relevant and revealing incidents. Large writing spaces for each project or incident help flesh out a comprehensive timeline of activities.

This helps map out alternative paths, rejected solutions, underlying assumptions, emotional journeys, and event consequences. “Making sense of critical incidents, project histories, and other narratives is an inductive process,” the authors write.

Structured stories are useful for knowledge elicitation. “Stories are memorable,” the authors explain. “Stories create pictures in our minds, give rich context and detail, build receptors, and provide vicarious experience,” they add.

Accelerated apprenticeship

Transfer of tacit knowledge is more complex than the above methods, and calls for shared experience and collaboration between the expert and the successor who may be also be a ‘near expert’. Both must agree to a series of steps for knowledge transfer through accelerated apprenticeship or mentoring in a short time frame.

This calls for trust and close interaction to internalise and mimic desired behaviours. This can include attending the expert’s conference and expo talks, and taking part in presentations and client negotiations. It may even involve learning the art of dining and drinking with customers, the authors jokingly observe.

Learning logs should capture the observations and discussions around them. Experts should give their successors time to practice activities on their own, and coach them along the way, the authors advise.

“The more active are learners’ brains, the more likely they will retain the lessons,” they urge. “Active involvement in your own learning has long been recognised as more effective than a more passive, spoon-fed approach,” they emphasise.

Live or recorded incident reports should be broken into sections so that after the context is presented by the expert, the learners can first discuss what they would have done themselves. This should be followed by showing what the expert actually did, and why.

Such ‘discovery in action’ is effective for learning. In the long run, this helps improves in situation awareness, sensemaking, and planning skills.

“Wise decision-making is a hallmark of deep smarts,” the authors explain. “In some cases, the combination of the expert’s knowledge and the different perspectives of the successor may lead to innovation,” they add.

The above frameworks and checklists are illustrated through a range of examples in the book. They include knowledge transfer through workshops and facilitation at GE’s Global Research Centres, knowledge vulnerability analysis at Baker Hughes, onboarding at Bank of America, ‘Ask and Discuss’ sharing at ConocoPhillips, and disaster management at New York Transit during Hurricane Sandy.

Other examples are Schlumberger’s classification of five levels of competency (awareness, knowledge, skill, advanced, expert). Face-to-face learning, a focus on quality, and use of collaboration tools helped Nucor Steel while acquiring other mills. Incentives helped with the success of mentoring initiatives at HB Fuller.

The frameworks and tools in the book may be useful in inter-organisational transfers of other kinds of critical knowledge as well, such as for pandemic management during the current coronavirus crisis. The checklists will be valuable in other kinds of knowledge-sharing activities as well in smaller organisational settings.

In sum, effective transfer of critical knowledge reduces mistakes, saves costs and time, improves succession planning, and narrows knowledge gaps. It also provides swift solutions, and improves competency of the next rung of smarts.

“Knowledge sharing is part of every job, every day,” the authors sign off.

Edited by Teja Lele