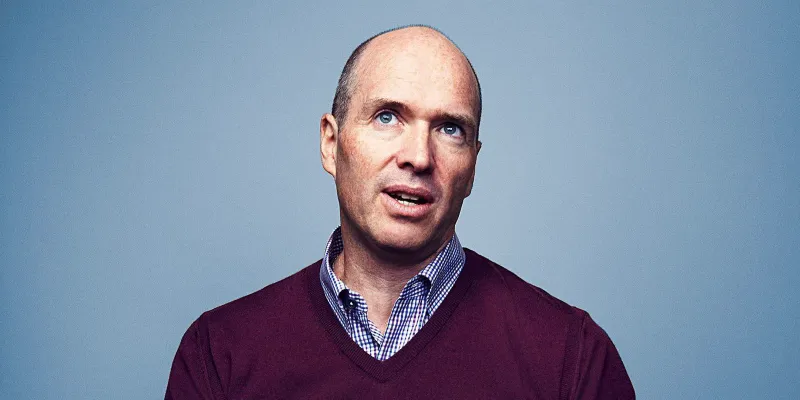

[YS Learn] What startup founders can learn from Ben Horowitz’s books and journey

Notable Silicon Valley investor, mentor, and entrepreneur, Ben Horowitz is known for his on-ground, raw, and real reasoning of decisions, cultures, and starting up. Here is what you can learn from the investor’s journey and books.

A powerful beginning in a book is usually a precursor of things to come – it hooks you in to read further. Silicon Valley investor’s Ben Horowitz’s book The Hard Thing About Hard Things too begins on a powerful note.

“Every time I read a management or self-help book, I find myself saying, “That’s fine, but that wasn’t really the hard thing about the situation. The hard thing isn’t setting a big, hairy, audacious goal. The hard thing is laying people off when you miss the big goal. The hard thing isn’t hiring great people. The hard thing is when those “great people” develop a sense of entitlement and start demanding unreasonable things. The hard thing isn’t setting up an organisational chart. The hard thing is getting people to communicate within the organisation that you just designed. The hard thing isn’t dreaming big. The hard thing is waking up in the middle of the night in a cold sweat when the dream turns into a nightmare,” he says.

During a casual conversation, Horowitz had said, “These were the words that got me hooked. These are things I face on a day-to-day basis and the geography the entrepreneur operates in hardly matters. It is universal.”

In his new book - Who You Are Is What You Do, Ben Horowitz is both pragmatic and practical. “Your culture is how your company makes decisions when you are not there. It is the set of assumptions your employees use to resolve the problems they face every day. It’s how they behave when no one is looking," he says.

The reason that these ring true to any startup founder is that the lessons are real examples and aren't management theories or jargons. Ben combines lessons from history and modern organisational practices with practical advice on how the management and executives can build cultures to weather good and bad times.

Here are some key points founders can learn from Ben Horowitz’s books- The Hard Thing and About Hard Things and What you Do is Who you are? and his journey.

Culture is not what you do more of what you don’t do

Like the product, market, growth, and business model, the culture in startups also has a tendency to change and transform. While a few things can change, the core values and culture remains the same and trickles down from the top. As Ben Horowitz puts it his book What you do is Who you are? - “Is culture - dogs at work and you in the break room? No, those are perks. Is it your corporate values? No, those are aspirations. Is it the personality and priorities of the CEO? That helps shape the culture, but it is far from the thing itself.”

He explains the crux is that managers think and behave differently and are shaped by their experiences. Ben says there may be some behaviours that you never endorse, but they get endorsement if leaders and managers get away with it.

In his book, What You Do Is Who You Are, he recollects a personal experience that says -

“When I was the CEO of LoudCloud, I figured our company culture would be a reflection of my values, behaviours, and personality. So, I focused all my energy on leading by example. To my bewilderment and horror, that method did not scale as the company grew and diversified. Our culture became a hodgepodge of different cultures fostered under different managers, and most were unintentional.”

Being a wartime and peacetime CEO

During the pandemic, most founders rushed and quoted that it is time to be a wartime CEO. But it isn’t easy or a simple change founders can make. As the book, The Hard Thing About Hard Things says - while in peacetime, a CEO will be looking to scale and recruit more people, in wartime, CEOs may continue to recruit but they also have to build functions and systems that execute layoffs. It is the wartime CEOs that help turn companies around in times of crisis.

There are few wartime CEOs people can quote, and one example is Steve Jobs. When he returned to Apple, and the company acquiring NeXT, in 1997, it was close to bankruptcy. He went on to lead a completely historical recovery. The iPod was launched in 2007, the iPhone in 2007, and the iPad in 2010.

How did he manage that? When Steve again took over the reins of the company, it had an array of products that were massive, had no clear strategy, and was losing money to the tune of tens of millions of dollars every quarter. Notoriously known for being a perfectionist, Steve ran Apple as if it were a small founder run startup till 2011. He is also known to have been a savvy negotiator, an important skill to hone during wartime.

Apple clearly needed someone to take tough calls and act decisively; in other words, it needed a wartime CEO. Steve ended up cancelling over 70 percent of Apple’s products and laid off more than 3,000 people. It was a tough and difficult call that earned him a lot of hatred. But it turned a $1 billion loss in 1997 to a profit of $300 million the following year.

Learn to delegate

As a founder, it is common to take responsibility and the entire weight of the company on your shoulders, especially when you are most invested in it. But for any vision to succeed, teamwork is needed. It is collaboration that brings in the best in people and for the product and company. As Ben puts it,

“You won’t be able to share every burden, but share every burden that you can. Get the maximum number of brains on the problems even if the problems represent existential threats.”

Edited by Rekha Balakrishnan

![[YS Learn] What startup founders can learn from Ben Horowitz’s books and journey](https://images.yourstory.com/cs/2/a9efa9c02dd911e9adc52d913c55075e/Ben1-1611577414048.png?mode=crop&crop=faces&ar=2%3A1&format=auto&w=1920&q=75)

![[YS Learn] Why the ‘always hustle’ culture can hurt your startup’s productivity](https://images.yourstory.com/cs/2/a9efa9c02dd911e9adc52d913c55075e/Culturetips-01-1609164196814.png?fm=png&auto=format&h=100&w=100&crop=entropy&fit=crop)