Shooting for the stars: How Pixxel is looking to make its mark in Indian space history

Describing their satellites as “MRI scanners for earth”, Pixxel is exploring new ways of earth monitoring and observation. In many ways, it is just getting started.

For Awais Ahmed, a boy who grew up on the outskirts of Chikkamagaluru in Karnataka, the concept of space came through bulky encyclopaedias. Like many, he too wanted be an astronaut. “I used to get fascinated by the shows on space that aired on Doordarshan and NatGeo,” he reminisces.

While he isn’t an astronaut now, his startup , which he Co-founded along with Kshitij Khandelwal, created history by setting off its third hyperspectral satellite Anand on the PSLV C54 Mission by the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO). Hyperspectral imaging refers to a type of technology that first emerged in the 1970s, which helps better monitor and observe activities on earth from space today.

Besides this, it has also collaborated with some big players in space like Elon Musk-led , to send small satellites with into space with hyperspectral imaging capabilities. Its ambition led it to a Series A funding round of $25 million in March, led by Radical Ventures, Jordan Noone, Seraphim Space Investment and others.

“Suppose a human body has internal bleeding. You don’t take out your phone camera to take an image and identify the situation; you need an MRI Scan to detect the problem. We are developing satellites with hyperspectral imaging. It works like an MRI scanner for the planet that detects pollution, diseases, and gases that otherwise are invisible to the human eye or normal cameras,” says Awais.

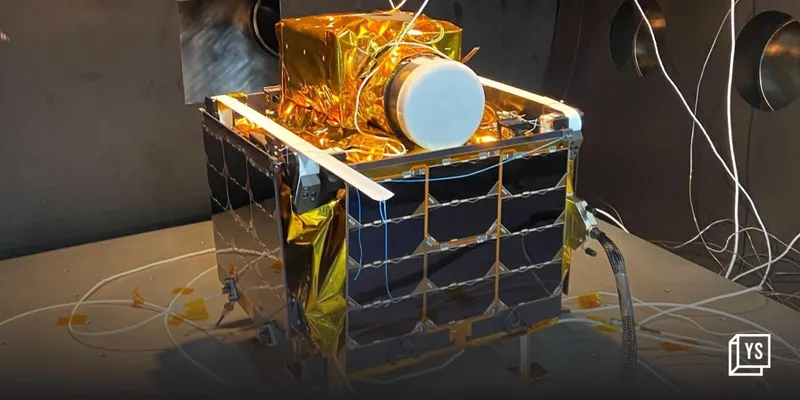

Pixxel's satellite Anand

All about Hyperspectral imaging

Anand has been built for earth observation applications to be used in agriculture, energy and climate sectors. The satellite had been in the works for nearly two years.

Weighing about 15kgs with over 150 thin sliced bands, it can observe the planet with greater detail than any other hyperspectral satellite today.

Anand is just the beginning. Developed in India, it will serve as a proof of concept that will be followed by the launch of Pixxel’s six fully commercial-grade constellation satellites next year, which are currently being built out of a facility in Bengaluru. Imagery from Anand will also provide the team feedback and inputs to improve the form factor and imaging capabilities of the next batch of commercial-grade satellites.

“The size of the satellite is decided by the quality of the imagery and the use cases of the imagery. It can be around 50 kilograms and the size of a mini fridge that you see in hotel rooms. Our new facility is around 30,000 square feet and has the capacity to develop 20 such satellites at the same time,” says Awais.

Pixxel’s first hyperspectral imaging satellite Shakuntala was launched onboard SpaceX’s Transporter-4 and is currently orbiting the Earth at an altitude of 550 km. It was the first of several Pixxel hyperspectral satellites that would form a constellation around the globe and would be able to cover any point on Earth every 48 hours.

"Technology-led interventions are necessary to enhance agricultural productivity and improve farmer incomes without further degrading the environment. Satellite imagery and remote sensing data are invaluable tools for forecasting agricultural output, regulating crop inputs, and even calculating how much carbon farmers are sequestering,” says Abhilash Sethi, Principal at Omnivore.

At the moment there are about 25 hyperspectral imagers deployed into space with 19 aboard satellites that are orbiting Earth. Some of them are CHRIS (aboard the Belgian satellite PROBA), DESIS (aboard the International Space Station), and HISUI (aboard the International Space Station).

Getting onboard SpaceX

Awais and Kshitij's first brush with SpaceX came as participants in a Hyperloop Pod Competition in 2017 while they were still students at BITS Pilani. SpaceX had announced an open challenge to build pods or vehicles that could travel at high speed inside a mile-long vacuum tube.

“Initially, the motivation for joining the competition was to meet Elon Musk,” says Awais with a smile. “But once we got through the first stage, we had to get serious and bring a team together. Of the 2,500 global universities that had applied, we were among the 20 who were finally selected by SpaceX to manufacture the pods.”

The team then had three months to build the prototype and ship it to Los Angeles.

“If a bunch of undergraduate students can build a hyperloop pod without any reference material, then we thought it should be easier to build a satellite. Because people have been building satellites for years and we can leverage the mentorship,” says Awais.

In April, Awais and Kshitij got another opportunity to collaborate with SpaceX but this time as Team Pixxel which is when they onboarded Shakuntala.

Awais and Kshitij with the Hyperloop Pod Team, BITS Pilani

Shaking up the space race

Until a few years ago, the spacetech industry was dominated by government-led space agencies. They were focused on research avenues since private players lacked capital and risk appetite. “While Indian spacetech startups did come up around 2013-14, they couldn’t sustain for long because of the absence of policy support,” notes Awais.

However, things have changed with the emergence of players like SpaceX, Boeing, Blue Origin, Dhruva Space, and Agnikul Cosmos.

“In 2020, things took a turn for the better when a slew of economic measures and policy approvals were introduced. This reduced a major chunk of uncertainty for people to start and invest in space tech startups,” he adds.

Though the industry has advanced, a hangover from the past looms. “Convincing experienced people from ISRO and others to shift to a startup is a bit of a challenge. Government jobs are still a secured lucrative offer for many… so hiring the right expertise is still challenging,” says Awais.

Nevertheless, it has still managed to build a team of nearly 85 members spread across India, the US and Europe.

For Pixxel, the primary source of revenue is selling data to clients. For instance, for a client who wants to monitor 1000 acres of land, Pixxel prices the imagery at $1 per acre. This gets further calculated on the number of weeks they want to monitor. Normally, Pixxel strikes multi-year deals with clients.

Another revenue source for the team is providing analysed data on the imagery. A report is provided to the client weekly and the price is based on the level of data analysis.

Exploring the horizons of spacetech has its own shares of twists and turns. Besides supply chain issues due to prevailing geopolitical challenges, the pandemic also delayed the initial phase of the production of satellites.

With private players exploring the spacetech sector, Allied Market Research valued the global space launch services market at $9.88 billion in 2019. It is projected to reach $32.41 billion by 2027 with a compound annual growth rate of 15.7 percent from 2020 to 2027.

For Pixxel, the future roadmap includes launching 24 satellites before 2025. It is also working on launching other imaging satellites besides hyperspectral imaging, with more collaborations in the pipeline to launch satellites to gain a better understanding of the moon, Mars and the asteroid belt.

“I think there is a huge opportunity for India to become one of the top players in spacetech both from the public sector and startups’ standpoints. There is no dearth of talent and then there is the infrastructure required for the development of satellites and rockets within the country… Hopefully, India will catch up in the next five years if we continue at this pace,” says Awais.

Edited by Akanksha Sarma