This queer, adivasi engineer has a next-gen solution to homophobic trolls

ShhorAI, an AI-powered bot built to combat hate speech on social media, has been created with tools to identify trolls in regional languages mixed with English.

Ever since school, Aindriya Barua’s (they/them) identity as a queer, neurodivergent artist was as central to them as it set them apart—often making them a prime target for bullies.

“Kids in school couldn’t wrap their heads around my personality, so they made jokes about my weight, my social awkwardness, and even my scores,” Barua tells SocialStory.

Armed with a notebook and pen, they found their own little sanctuary under the desk or behind the cupboards, where they sat illustrating, writing code, and journaling, about the challenges of navigating these identities in an intolerant environment.

Countless such musings over many years have positioned Barua at an important social and cultural juncture today, as the founder of ShhorAI, an AI-powered bot built to combat hate speech on social media, with a special focus on marginalised community safety.

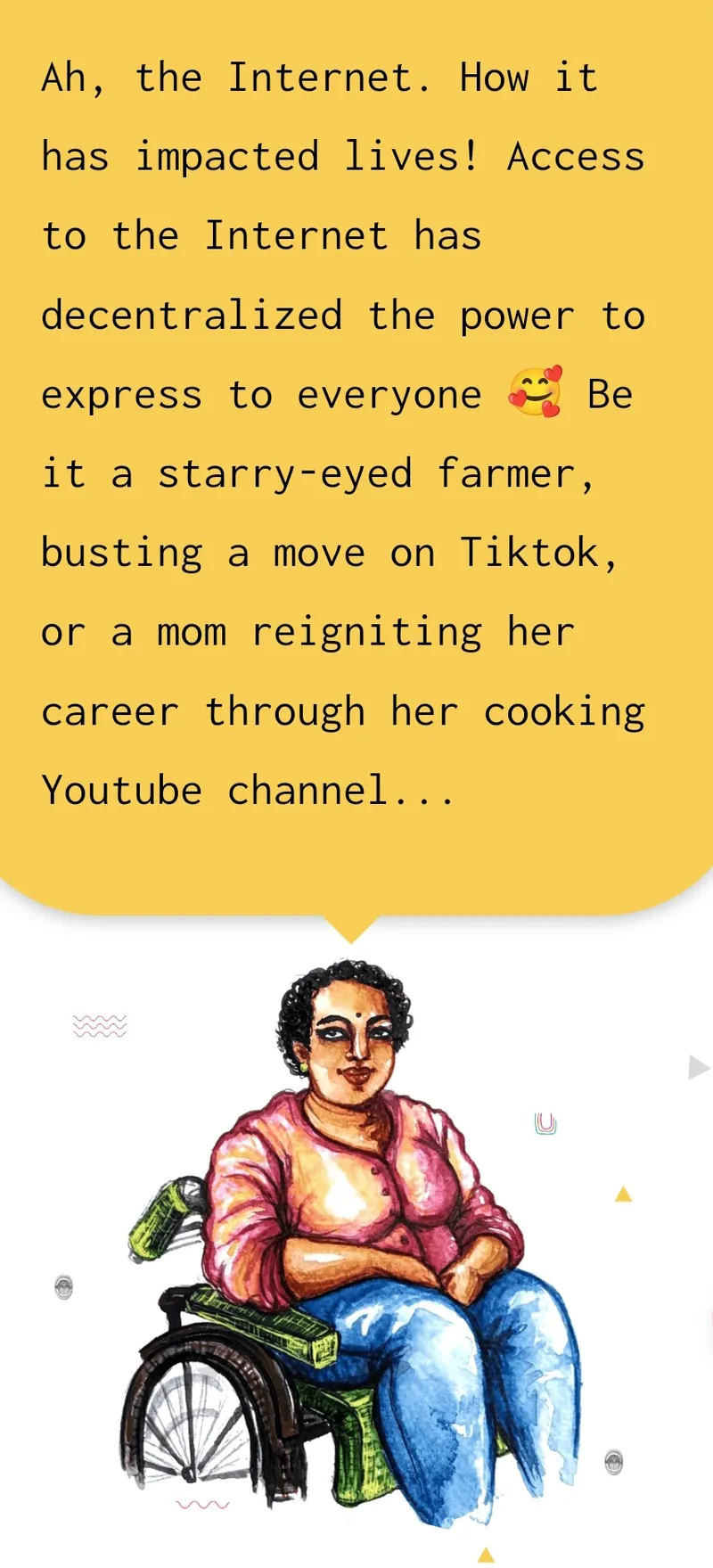

As Barua’s art and activism spilt over online, they realised that the bullying only became more pervasive and unforgiving on the internet, which they saw as a macrocosm of their school and college.

“I created ShhorAI as my right in restoring faith,” says Barua, “for scores of others like me to know they have a tribe within this very system that values and protects them.”

Reclaiming opportunities

Barua was born into the Mogh adivasi community in a remote village in Tripura. Assigned female at birth, they grew up to identify as non-binary.

While growing up on the autism spectrum came with its own challenges, Barua says the best thing to happen to them was a course in coding that their school offered. “My neurodivergence gave me the tendency to hyperfocus on certain things. For me, they became coding and art,” they say.

Even before getting their hands on a computer, they started coding by hand on paper. “My teachers gave me full marks for my algorithms, and this inspired me to keep building my knowledge,” says Barua.

As a young adult, they put their skills to test by building an IoT device for their parents’ farm, which could sense the moisture in the soil; and an incubator that maintained the temperature for eggs.

That was the turning point where Barua realised they could put their skills to help people.

By the time they began identifying as non-binary, Barua had enrolled into a computer science course in a college in Kollam, Kerala, where they experienced intersectional discrimination and homophobia first-hand.

They faced intimidation and humiliation from fellow students, and were boycotted from group activities. “In my final year project, which had to be done in a group of five, I had no one with me,” says Barua.

In what was a desperate attempt to complete the project, Barua took some days off and left for Coimbatore to do a course in AI and NLP at the Center for Excellence in Computational Engineering and Networking (CEN) at Amrita School of Engineering. Here, they wrote a paper on how machines interpret the meaning of texts in regional languages and extract useful information, and got it peer-reviewed and published it for their final year project.

Even as their day-to-day challenges pulled them deeper into their fight for equality through art and activism online, their experience of being relentlessly trolled showed them how pervasive and dangerous it could get.

“Some of these troll pages were familiar to my classmates from college, and I suddenly found my phone number and email ID being circulated online. I began getting threats every day, asking me to publicly apologise for my pro-queer, feminist, and anti-caste artwork,” says Barua.

“When you are a minority in all these categories, you don’t set out to be political; anything you share about your lived experience becomes political. You are also then compelled to look at intersections - how being a woman and Dalit, queer and Muslim, and so on, make you softer targets,” they add.

Sifting hate from Hinglish

Barua also realised the importance of language, especially with code-mixing, or intermingling of multiple languages that was common on Indian social media.

“I saw that there were far more complications in AI and NLP programming in languages of the Global South, when compared to those of the Global North,” says Barua. “Code-mixing created a complex language with variable spellings and pronunciations, making banning of abusive words tricky.”

“Most abuse in Indian social media happens in Hinglish— code-mixed Hindi-English,” they say.

Forty-five volunteers helped Barua create a vast repository of Hinglish comments numbering 45,000 to date.

Barua decided to use AI to understand the context of these sentences beyond fixed rules—for instance, to identify when people from the North East are caricatured with references to certain foods, or highlight casteist or classist undertones. Through calls on Instagram, they invited people to share links to their own posts that were targeted by trolls.

They then used a scraper (a method of collecting content and data from the internet through code) to collect offensive comments from these links. A community of 45 volunteers helped Barua manually read and classify thousands of such references as 'hate comments', resulting in a vast repository of Hinglish comments numbering 45,000 to date.

Barua’s algorithm can scan, identify, and categorise hate speech in text. Besides Hinglish, the bot can also be trained to detect offensive content in regional and vernacular languages. It can detect code-mixed typing, wherein even asterisks, exclamations and other symbols used in an expletive can be detected by taking into account the context of their use.

By the end of 2022, ShhorAI’s current version was built and demonstrated at the United Nations Population Fund’s (UNFPA) Hackathon on solving technology-facilitated gender-based violence. Barua was second runner-up at the competition. By mid-2023, the website was ready.

Barua is currently reaching out to social media platforms to integrate the technology into their community safety systems.

In a 2021 survey conducted by the Trevor Project, a US-based nonprofit that helps young LGBTQIA+ people in crisis, 42% of respondents said they had been bullied electronically, including online or via text message.

At the same time, 69% reported having access to online spaces that affirmed their sexual orientations and gender identities.

When the little space that social media has created for communities with multiple marginalisations is taken away, they are pushed further to the sidelines, says Shoi (they/them), a queer dalit artist and social work professional from Kolkata who has been collaborating with Barua on LGBTQIA+ resource projects.

“With initiatives such ShhorAI, we can at least try to take space and create dissent, because dissent is needed in a society for all voices to be heard,” they say. “Particularly in regional languages where hate comments are harder to challenge and report, the online hate takes away from us the few rights and avenues we have to express ourselves, and this causes systemic mental distress - something we have been fighting against for years.”

Edited by Jyoti Narayan