Sarson ke khet, a Punjabi kothi, and bonfires: The perfect Lohri stay

In Nawanpind Sardaran, a small village in Gurdaspur district, an idyllic homestay set amid yellow mustard fields and tall trees makes the case for a slow holiday.

I have been wanting to visit the Golden Temple for the longest time. I planned two trips to Harmandir Sahib, the pre-eminent spiritual site of Sikhism, but had to willy-nilly cancel them at the last moment. But like most people with faith, I persevered. No one really visits a religious site at will; one needs to wait for the right time, for the bulawa, the summons from the higher authority.

Fifteen years after I put Amritsar on my wish list, I finally made my way to the second-largest city of Punjab. We did all the things that we had planned to: pay obeisance at Golden Temple, take in the sombre atmosphere at Jallianwala Bagh and Partition Museum, attend the high-on-theatrics Attari-Wagah Border ceremony, and shop for phulkari suits and juttis. And of course, over-indulge our taste buds with the most delicious food: chhole-kulche, dahi bhalle, Amritsari macchi, rajma-chawal, lassi, cold phirni, and piping hot gulab jamun.

We city slickers decide to end our sojourn in Punjab by experiencing its rural character. The state draws its name from the five rivers—Sutlej, Beas, Ravi, Jhelum, and Chenab—that course through its fertile plains. Over centuries, it has played host to people from different ethnicities and cultures, forming a civilisational melting pot. Punjab’s robust agricultural ethos is mirrored in the many festivals its lively and warm people celebrate, be it Lohri, Basant, Baisakhi, or Teej.

Our car cruises along the highway, making short work of the 75-odd kilometres that separate Amritsar from Gurdaspur.

Leaving the city behind, green fields take the spotlight. Varied hues of green flank either side of the road, the fertility of the soil a reminder of the fact that India’s green revolution began in Punjab in 1965. Our driver too offers some statistics to chew over. Wheat production in Punjab grew from 1.9 to 5.6 million tons from 1965 to 1972, he tells us, with pride in his voice.

Not so long after, we spot heaps of kinus (a type of oragne) piled up on either side of the road and demand a pit stop. The fresh juice seasoned with black salt is spicy, aromatic, and leaves behind a refreshing zing. And then we head to Nawanpind Sardaran, a village in the heartland of Punjab that best showcases the state’s rural and rustic beauty.

Home to about 750 people, the pind (village in Punjabi) combines pastoral beauty and cultural richness. It has made a mark on the rural tourism map by winning the Union Ministry of Tourism’s Best Tourism Village of India 2023 award. A total of 750 villages from 31 states and union territories applied for the award, and Nawanpind Sardaran was among the 35 chosen ones.

The village, which dates back to the late 19th century, was founded by Narain Singh, who put down roots here and invited other people to do so as well, creating a small community of farmers. Singh built a 'haveli' as not just his living quarters but to also store produce and agricultural implements, and interact with farm workers. In 1886, his son, Beant Singh, built a house which is now called the Kothi.

Today, his great-granddaughters, Gursimran Kaur Sangha, Gurmeet Rai Sangha, Manpreet Kaur Sangha, Gita Sangha, and Noor Sangha, and their mother, Satwant Kaur Sangha, have helped put the village on the map through their conservation efforts and by helping villagers build modern livelihoods.

Located on the edge of award-winning Nawanpind Sardaran village, The Kothi promises a taste of Punjabi culture.

The car pulls up into the driveway of the Kothi, located on the edge of the village and Upper Bari Doab Canal. The red-brick façade has all the characteristics of a traditional Punjabi kothi; it blends Punjabi aesthetics with colonial architecture. An expansive verandah invites us into a formal drawing room, pukka sahib in nature, with floral patterned sofas, old wooden furniture, and a fireplace to boot. We’re served some more of the fresh kinu juice, which obviously no one refuses, and then step into the courtyard.

Courtyards have been a part of village homes in most states for centuries. They date back to the Indus Valley Civilisation and have since then served as the core of the house.

Built in red brick, the traditional kothi blends Punjabi vernacular with colonial architecture.

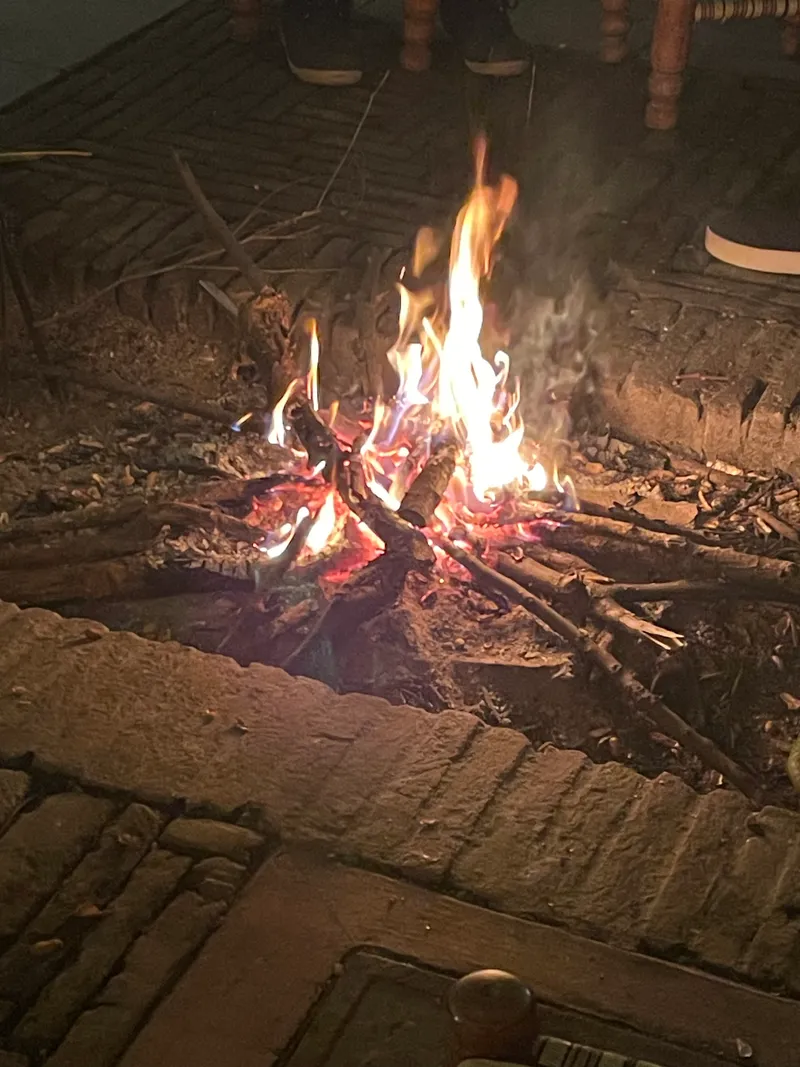

At the Kothi too, the courtyard seems to be the nerve centre; all rooms open off it as does the kitchen and it’s where people congregate for tea, breakfast, or meals. I spot the remains of a fire in the centre; clearly, even the bitter cold of the night can’t keep people away. I see the staircase leading up to the rooms and somewhat expect Simran (of Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge fame) to come traipsing down the stairs for Karwa Chauth celebrations!

Surrounded by yellow mustard fields and tall trees, the Kothi is the ideal place for a slow escape. The wintry weather makes it even more plausible—what could be better than sipping ginger tea and scarfing down mathris as we look at the indie pet making its way around the courtyard?

Manpreet, who has been living in the US since 1994, recalls that the family gave up the home after her father, an officer in the Indian Air Force, died in a crash in 1982. It was only in 2008, before the wedding of the youngest sister, that the family returned to the Kothi and decided to renovate it for the celebrations.

The Kothi arranges a bonfire in the central courtyard on wintry evenings - perfect to sit around and enjoy a hot meal.

Delhi-based Gurmeet, a reputed conservation architect, decided to renovate the family home. “We had to do quite a bit of work to ensure that the restored building responded to the original design,” Gurmeet says, adding that the sisters finally fulfilled their father’s dream of adding an upper floor. “We added two bedrooms and bathrooms, redid all the services, and put in rainwater harvesting facilities,” she recalls.

The renovation has served the Kothi well as the old structure now offers all the modern trappings important to urban travellers. Footfalls have slowly risen with more takers for slow tourism and as many travellers pick unusual experiences instead of mainstream destinations.

With the family home located in the heart of a small village, it offers tourists a chance to experience Punjabi life and culture.

“Apart from no-itinerary stays, we can arrange visits to the dairy farm, teach culinary enthusiasts how to cook specific Punjabi food like maa ki daal or kale chane, or organise tractor, tonga or gadha rides,” she says. Other activities include visiting nearby historical and ecological sites, interacting with villagers, and helping with seasonal crop activities. Keen to help villagers, the sisters have employed men and women from the village at the Kothi and Pipal Haveli (run by Gurmeet).

“Apart from the cooks and the serving staff, we have trained a dancing troupe to showcase the cultural heritage of Punjab and women in massage therapies,” Manpreet says.

A sun-dappled verandah with a self-service tea and coffee station nearby is the perfect reading nook in winters.

After spending our evening with a walk in the mustard fields and watching the sun go down, we return to the Kothi for an excellent meal that showcases the best seasonal produce: sarson ka saag, chicken curry, matar aloo, tadka dal, salad, makki ki roti, and rice. Piping hot food on a wintry evening has never tasted better. The meal ends with a generous helping of delicious gajar ka halwa.

Our genial host plans an itinerary for the next couple of days: an early morning visit to the village, a sunrise walk in the agricultural fields, breakfast in the rasoi or central courtyard, and an evening walk along the canal followed by pakoras at Toti’s, a 40-year-old local establishment.

Long walks amid yellow mustard fields as the sun rises or sets are the perfect itinerary when staying at The Kothi.

Unsure of whether city-dwellers will be happy without being busy, she suggests a few more options nearby: Chotta Gallaghara Gurudwara, Kishankot Temple, Masania Dargah, Aqsa Mosque, Guru ki Maseet, Dera Baba Nanak, and Kartarpur Sahib (across the border).

The family, though, is happy to take a break from the tourist trail. We’re content to take the time to sit back and appreciate the beauty of the countryside. The colours. The views. The rustling of the leaves. The birdsong. The flavours. And the peace!

Edited by Kanishk Singh