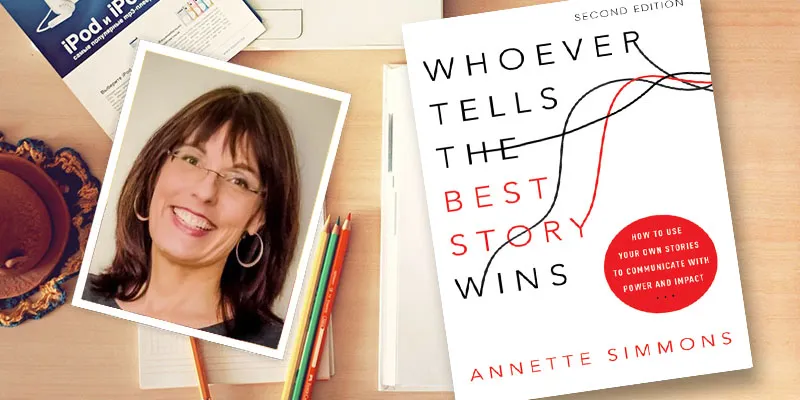

'Iterate till you build a good entrepreneur story' – Annette Simmons, author, ‘Whoever Tells the Best Story Wins’

Annette Simmons is the author of Whoever Tells the Best Story Wins (see my book review). Her three other books include The Story Factor, A Safe Place for Dangerous Truth, and Territorial Games: Understanding and Ending Turf Wars at Work. She is the president of Group Process Consulting, and her books have been translated into 11 languages. Annette has a degree in marketing from Louisiana State University, and has worked at Ericsson and J. Walter Thompson.

Annette joins us in this exclusive interview on storytelling, audience impacts and iterative design. (See also the YourStory Changemaker Storytelling Canvas, a free visualisation tool for entrepreneurs and changemakers.)

YS: How can storytelling help in the different stages of the entrepreneurial journey?

AS: Entrepreneurs and founders can use the story categories of who I am, why I am here, teaching, value in action, vision, and ‘I know what you are thinking.’

Every entrepreneur should know who they are and why they started their business. They should test these stories until they can tell them in a way that inspires others. Their origin story should be authentic and rigorously true. Funders and potential customers will test it, investigate, and make generalised judgments that if you ‘invent’ your origin story you will likely ‘invent’ all kinds of things.

YS: How should innovators strike that delicate balance between ‘Stick to your vision’ and ‘Adapt to a changed world?’

AS: Vision is value based and no matter what circumstances occur, the vision doesn’t need to change. My vision is to bring humanity back to places where it has gone missing. Whether I’m at NASA, Microsoft, or at home struggling to write an article – that’s still my vision. Vision is the primary conflict between what you want to create and what stops you.

YS: How was your book received, and how do you see storytelling connect with different kinds of audiences?

AS: Most of the marketing and public speaking professors who use Whoever Tells The Best Story Wins as a textbook really like the new edition. The only unusual response was when a professor who specialises in public narrative told me he will stick with the old version. He and his students – mostly executives from NGOs and public health services – didn’t like that the second edition had so many examples from corporate storytelling.

Also at a conference for nutritionists, I was asked to delete an example from Coca-Cola (nutritionists call it chemical sugar water) for the same reasons. I’m happy people care about ethics. I too, hate when storytelling is used for evil – like scams and fraud – but the storytelling skills and tools are value neutral and I want to know as much as I can about what creates an experiential emotional impression.

I don’t care where it came from if it works. Thus, I used the Coca-Cola example and challenged the nutritionists to learn how to associate happiness with exercise as effectively as Coca-Cola has associated happiness with Coke.

YS: What are some notable new examples of impactful stories and storytellers you have come across since your book was published?

AS: He’s not new, but I like Marshal Ganz’s approach to grassroots organising. He calls it public narrative – and it was instrumental to the 2008 Obama win. They start with the story of ‘ME’ then ‘WE’ then ‘NOW.’ But the really magic is that people come together and share personal stories. It’s bonding. It doesn’t matter what the story is.

I use this in my hometown where racial tensions bubble under the surface. I’ve produced two shows where a mixed race audience listens to a lineup of mixed-race tellers sharing a personal story about a time when they were excluded. Black or White, no matter your ethnicity, we’ve all been excluded.

Sharing personal stories bonds people and anchors them in our common humanity. When people see this is a story we all share, we are no longer on opposite sides, we are united. I use it with workgroups troubled by dissent – get them all (or even some) to tell their ‘who I am story’ and they realise they are all good people working for the same thing. It shrinks the disagreements down to size.

YS: Which governments have you come across that also have storyteller roles?

AS: As far as I know, Singapore is the best example of a transparent and explicit use of storytelling. But every government chooses the stories they tell when they choose curriculum for their schools, decide which statistics to report, and how to dress their military.

Even Pope Francis plays a storyteller role when he dropped the gold, fur and expensive vestments to wear a simple cassock. His travel plans tell a story. Before he arrives in the US, he will visit Cuba – tiny and poor in comparison to the US. Storytelling has happened throughout human history with or without the official title, and naming someone a storyteller doesn’t mean it becomes more effective.

YS: What is your current field of research in storytelling?

AS: I am interested in stories and storytelling that can improve society. For instance, public health could be using stories to change unhealthy behaviors. In many cases, I think storytelling will save more lives for less money than ‘teaching’ or ‘information’ campaigns. The only problem is that public health officials are so wedded to linear thinking and ‘evidence-based’ studies that kill the magic of storytelling in the process of removing variables. Storytelling is always variable.

That’s why I’m excited by the popularity of the UX (user experience) process and development of design thinking, because these two models help me break people away from predictable bad process habits that kill good storytelling. Normal work process follows a more scientific method of finding problems, searching for root causes, orchestrating a plan, and sticking to the plan.

A master storyteller is constantly experimenting with ideas and constantly discovering, adapting to, or changing the context so a story feels more real. Before I learned about UX, I used my own model to make the distinction between objective and subjective thinking. I had to demonstrate that in the highly variable, unpredictable, and ambiguous world of opinion (a.k.a. story) we constantly take lots of risks, experiment, and keep adapting.

In the past, everyone wanted a recipe so they could do it right, get it perfect, and tell stories guaranteed to work. That’s just not how humans operate. What works in one situation, may not work in another. You have to stay in relationship, keep listening, and adapt.

Like the UX designers say: iterate relentlessly.