Going beyond startups to try an all-inclusive jugaad revolution for grassroots innovation

The annual ritual of Union budget is long over and the dust seems to have settled, until the next Parliament session at least. There was much print spent on the rural focus, and rightly so. Not so hidden in the budget speech was a small bit of information that, however, didn’t make it big in the headlines-

“A special patent regime with 10 percent rate of tax on income from worldwide exploitation of patents developed and registered in India,” said the Finance Minister.

You place this in the framework of Skill India, Startup India, Make in India, Standup India and what we are possibly looking at is a paradigm shift in policy intervention. The government seems to be correcting errors of the past and it started with admittance. In a prelude to the Startup India summit, President Pranab Mukherjee graciously admitted, “We are late.”

It triggered a follow-up question though - What are we really late for? And further…

Is the delay limited to not encouraging startups? Or not easing up policies for doing business? Or being late in providing impetus to Indian manufacturing?

Or are we late in addressing much larger, graver challenges? Like being a little too late in creating an ecosystem for innovation and entrepreneurship?

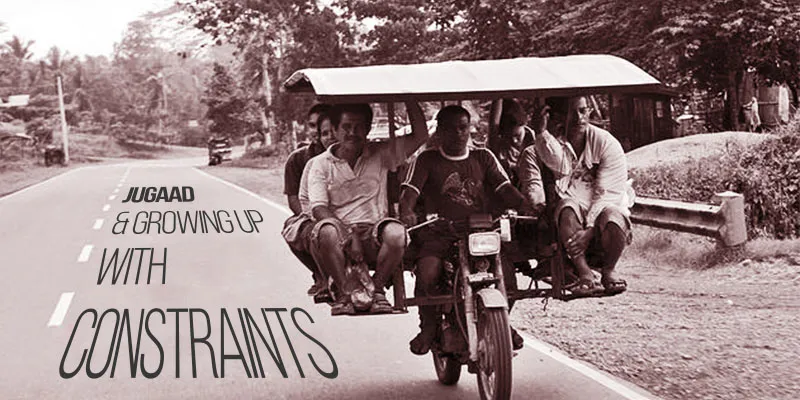

While the policy changes being initiated now would start fitting in the big jigsaw puzzle, the larger challenge is to bring a deeper socio-economic change - an era of democratised, bottoms-up innovation. A jugaad revolution.

Why jugaad ? Why revolution ?

Considering how creatively we fit jugaad into multitude of situations, it’s tricky to define the word, clinically. Here are some common usages, a mix of both positive and negative

- Rudimentary, make-do ‘kaam chalau’

- Political or interpersonal leverage to get your work done, by hook or crook

- Grassroot, Bottom of the Pyramid innovation

- Frugal engineering

It’s common to see people talk about why we should change our jugaad mindset (1 ,2) while in the same breath also expressing pride in our inherent ability to innovate in constraints (3,4). Our attempt is to blatantly use the positivity of this popular, possibly clichéd, word as a starting point of an innovation-driven culture.

Be it a small factory manufacturing electrical components or a micro lathe workshop, their day-to-day work challenges go from ‘Let’s do something to fix it ourselves’ to ‘ Let's mechanise it ourselves.’ There is no better word that can reflect this range- from simple tinkering to real frugal engineering. The small but significant modification would be to add ‘excellence’ to jugaad; transforming ‘random innovation streaks’ to a ‘sustainable innovation culture’. A revolution of sorts in our approach!

Where do we currently stand ?

Consider this:

- In 2014, India filed 1,428 international patent applications as against 57,385 by US, 25,548 by China and 13,117 by South Korea, according to World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO).

- India registered a high patent filings by Non-Residents at 78 percent, an indicator of lack of awareness in the domestic industry about the benefits from intellectual property.

- Innovation Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF)’s recent study titled Contributors and Detractors: Ranking Countries’ Impact on Global Innovation ranks India at 54t h place out of 56 countries.

- In World Economic Forum(WEF)’s report on Global Competitiveness, we have improved our competitiveness ranking but in the same report on Innovation and Sophistication parameter India has slipped from Rank 26 in 2006-07 to Rank 46 in 2015-16.

The jugaadu, innovative Indian seems to be a fictional character. A view echoed by Narayana Murthy and more recently by Piyush Goyal as well.

While the data indicates our deficiencies, it is pertinent to acknowledge efforts by agencies like the National Innovation Foundation, Ahmedabad. Since inception in 2000, NIF has been engaged in documenting, commercialising and providing IP support to the grassroot and traditional innovators. It has documented more than 2.1 lakh technological ideas and traditional knowledge practices and filed 743 patents. Further, Ministry of MSME has schemes like ASPIRE and SFURTI aimed at providing increased support to grassroot enterprises. More recently, we have MUDRA Bank and Stand up India as well.

It gives hope that directionally we are moving forward to recognise the larger potential India holds. But are these steps sufficient and well-paced? The four data points above indicate much distance needs to be covered. Time would measure the success of the schemes but for now we seem to be not only late but possibly have walked backwards a few steps in the last 68 years!

The aim of this article is to evaluate the current innovation ecosystem at grassroots and not a prescription on what the government should or shouldn’t do. Although sceptics may question the Rs 200-crore budgetary allocation (FY14-15) to the ASPIRE scheme, there is no denying that cumulatively there is enough ideation and direction.

But execution, not ideation, is our current challenge.

What are the key challenges to execution?

Broadly, there are three challenges in building an effective grassroot innovation ecosystem and the problems find a good simile in Indian agriculture:

- Size of the field

- Poor irrigation system

- Separating wheat from chaff

Size of the field refers to the challenge of the geographical spread which makes it daunting for the government to take these policies to the last mile, akin to taking agri policy benefits to remote marginal farmers with small land holdings

Poor irrigation system indicates the weak infrastructural support like tinker labs, incubation centres, seed funding et al, which are key enablers to innovation and risk-taking.

Separating wheat from chaff implies segregating the marketable, impactful jugaad from mundane kaam chalau (stop-gap) kinds.

Just like agri policies need to differentiate large farm holdings from the marginal farmers and choose between canal versus drip irrigation, the innovation enablement has to separate corporate or institutional R &D from grassroot-enablement.

In brief, the key challenge is the depth and targeted delivery. We need a better segmented and micro-managed approach in execution to help us achieve faster results.

Some starting points could be

- Refresh the way we look at grassroot innovation

- Right segmentation for targeted delivery

- Replicating the enablers that work for startups

Refreshing our view of grassroot innovation

Md Hussain from Bijapur, a Class-VII dropout, has taken a small initiative that makes him stand out in his peer group of informal tour guides in and around the Gol Gumbaz. With the help of his two moderately educated friends, he created a short audio file describing the history of Gol Gumbaz. He shares this audio clip with his customers over Bluetooth when they avail his guide services. He also ensures to note the mail ids of his customers and sends them regular updates on the events in and around Bijapur. With the help of some town artistes he is now adding more sound effects and voiceovers. Is he a grassroots innovator? Before your judge, I must remind that it’s a slightly different paradigm.

What seems like a significant innovation for the grassroot worker may look like a rudimentary, welded, lever-press (or just a sound recording!) to those up the value chain. While the impact of high-end innovations would create multi-billion dollar corporations, the grassroot level experimentation may just be solving or adding value to a day-to-day chore. Importantly though, the cumulative socio-economic impact of grassroot innovation is much higher. It empowers! It is important to set the expectations right from what to achieve with jugaad. It is a tool to improve skill and improve living.

Let me admit Md Hussain and the story above is fictional, but I hope it illustrates the paradigm where to place the grassroots innovation. R&D at institutional or corporate level and innovation at grassroots achieve somewhat different objectives in the short to medium term. Hence, the differentiated flagging such as jugaad revolution can help convey the right message. The stories of MittiCool or drawing the water using a bike, as mentioned by Prime Minister Narendra Modi at the startup summit, or the pressure cooker based coffee steamer and many more would just grow manifold if people are encouraged with deliberate and consistent policy efforts. In the long term, if a large number of people are thinking creatively, the probability of finding more patents and Unicorns increases multi-fold.

What segment? The Pareto Principle challenge

Imagine we are in utopia, where each can ideate and convert their ideas, without the limitation of capital or a penalty for risks. Would you assume it would bring faster solutions to the world’s problems? By democratising innovation, world can be made a better place, faster. The nearest example would be open source software.

But we don’t live in utopia. The resources are limited and therefore a system that rations with expectation of fast results. Any intervention or support system ends up targeting low hanging, quickly ripening fruits i.e lower risk, better educated, more secure segments of society, with a hope that it would go down the pyramid if resources permit. This leads the problem of largest getting the maximum and being the determinant of result; everything else is a long tail. The Pareto Principle.

For example if an incentive is given for research and success is measured by the quantum of commercial success, more often than not it would be skewed in favour of larger entities. For a real awakening and fairness at the bottom of the pyramid, the approach needs redefined success measures.

At the Bottom of the Entrepreneurship Pyramid (BOEP) are the Micro entities and smaller Rural Enterprises (MRE for simplicity). As per the fourth census on MSME 06-07, micro enterprises are 99 percent of the total unorganized MSME universe. Rural enterprises are 60 percent of the total universe. MSME as a segment is just too wide to expect due importance for the micro enterprises. ‘M’ gets lost in favour of SME and rural is just a tail. It may be worth looking if micro + rural, being the most vulnerable segments of the entrepreneurship pyramid, are focussed exclusively. It would help reduce the top-end bias implied by the Pareto Principle.

At the risk of broad generalisation, MREs are mostly sustenance and salary-substitution businesses than real entrepreneurial ventures, with low capital access. Hence the low-risk appetite and preference for low value-add businesses like retail and repair in this segment. This in no way implies any lesser potential to innovate, though. It does indicate the failure of system to provide the required support.

For MREs the challenge to break the glass ceiling is much more daunting compared to the larger entities or even the modern tech startups. The cost of failure for them is much higher. The targeting has to go beyond the loans under MUDRA or Startup India. It needs to accept and support incremental products with a reasonable margin for failure.

All startups are not startups

Compared to the technology startups, MREs operate in a very different world. Between the celebration of e-commerce, hyperlocal and unicorns, it is unlikely that we even think about a small repair shop, an agri implement trader, micro-steel cutting unit or lathe workshop. So while we talk about encouraging risk taking and entrepreneurship under Startup India initiative, all of these not-so-glamorous entities are somehow lost in translation.

Some conspicuous differences between modern startups and MREs:

- Access to capital- VCs, angels, seed, incubators versus money lenders, who are no angels

- Education – marquee pedigree versus uneducated and above

- Technology – knowledge of world trends versus On-the-job, hands-on work experience and no access to experts.

- Collaboration – from cloud to pay-per-seat workspaces to moonlighting Android developers to logistics tie-ups versus remotely located, unsupported ideation with challenge of even the raw materials.

The list is short and indicative, but some contrast is visible. While there is a well-evolved parallel support system for the new age startups, for BOEP there is only a patchwork of government policies, significant but insufficient. It would be worthwhile to nurture similar best practices to make the revolution self-sustaining at grassroots and as a result build up more impactful innovations over the long term.

Tying more loose ends

There is enough ideation by the government to tie the loose ends, and many of the improvement areas are already work in progress. The obvious ones being,

- Increased infrastructural support through incubators, tinkering labs

- Specific seed funds for grassroots innovation

- Support for commercialising the products

- Encouraging public-private partnership

- Improved intellectual property regime

I only add two thought experiments that may, hopefully, trigger some ideas to scale this up, faster.

- Innovation adoption/internship scheme – How do you exponentially build the infrastructural support as well as access to expertise for grassroot innovation? One solution may lie in linking our education system, especially at college/university level. Assume if each college in the country is made the focal point for supporting innovations in the nearby villages! And if the young and bright students from the nearby technical institutes do short rural projects to create a local level solution, say under the guidance and resource support from local DM/Collector and the college. Due credits in the curriculum can be a fair way to incentivise this process. Imagine if the likes of Md. Hussain get a partner in a final year IIT student. If these two disparate universes can be integrated successfully, needless to say local problems would find faster, effective solutions. The first impact would possibly be on agri productivity, traditional crafts and sanitation. We are integrating the grassroots to knowledge mainstream!

- Celebration of innovation at grassroots: NIF recently concluded the ' Festival of Innovation’ at Rashtrapati Bhavan where 60 innovations, selected amongst the thousands, were showcased. But we need to go beyond symbolism. Indulge me by assuming jugaad trade fairs or exhibitions at each block level. Assume further each village celebrating a jugaad dangal of rural creativity. And imagine further a school-level jugaad contest on creating new things with locally available raw materials. Or may be a jugaad museum could be the starting point. Multiplying the celebrations at the grassroots is the first step to making innovation truly accessible.

These engagements can help democratise innovation.

Innovate India- imagining jugaad revolution.

Have you seen the village children playing cricket with a ball made of a newspaper, covered with rubberbands, sliced from a cycle tube? Or a vendor sharpening the knife with a modified cycle? There are many such examples that reflect our inherent ability to adapt and solve larger problems, with whatever little is available. The IT revolution and now the startup evolution, though serendipitous, exemplify this ability as well. The jugaad revolution, however, requires a much more deliberate approach to be impactful. It can uplift and empower in a true sense. Once the frameworks of Startup India, Standup India, Skill India, Make in India move in tandem, as part of the larger ecosystem and executed to the last mile, we can truly unleash a creative, innovative India.

‘Innovate India’, now!

Sixty-eight years has been a long wait.

(Disclaimer: The views expressed in the article are personal and not of the organisation(s) the author had or is working for)

(Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of YourStory)