How a contemporary arts festival in a Himachal village is making its residents proud

A contemporary arts festival in a Himachal village that is making its residents proud and why it is important to take art out of cities into more inclusive settings

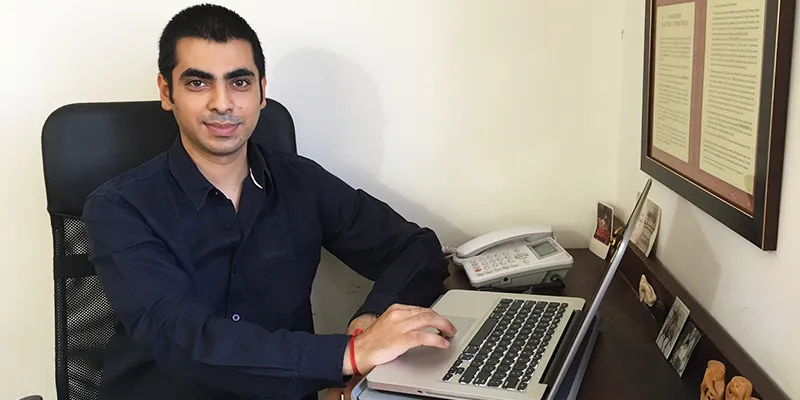

India has a unique way of making people its own, and it was no different for Frank Schlichtmann, who first came to the country as a three-year-old with his parents in 1969.

Today, the 50-year-old German is the reason behind putting Gunehar, a quaint hamlet in Himachal Pradesh, on to the world map. He is the Founder of ShopArt ArtShop, a first-of-its kind conceptual arts festival that invites contemporary artists to live and work along with villagers for a month, using local material and crafts to produce site specific art installations.

The festival will conclude with a week-long exhibition from June 7, which will not only demonstrate the end result of the artists’ work but also incorporate typical local mela elements, concerts, performances, screenings, and podium discussions to reach a broad cross-section of the society.

How it all began

“I wanted to find a meaningful way to ‘open up’ the village to a larger world since in today’s day and age, it’s not possible to remain secluded,” shares Schlichtmann.

The idea was that conceptual artists live in the village and work in/with the spaces the village offers, primarily empty, economically unviable shop-spaces, in front of curious and sometimes prying villagers and visitors. This experiment has made our village what it should be: an exclusive space not associated with mass-tourism.

This is the second edition of the festival, the first having been held in 2013. It was not easy, however, to associate a hitherto unknown venue with arts, aesthetics and responsible tourism. Then again, determination is the art impresario’s finest qualities.

When I thought of the idea first in 2012, I was determined to go ahead and host it despite having no help and no external finances. I ended up paying for the whole event myself, from my own savings. In the long run, I find that that was a good thing because I knew the vision clearly and could establish the event without compromises.

Why he chose Gunehar

“We first came to Himachal in 1973, I think. It was a different world altogether, much more simple. We lived in an old mud house near here and there was no electricity. Drinking water had to be brought from the chashma (fountain). We had a fabulous time, full of beauty, and awe,” he reminisces fondly.

Gunehar still retains some of that old-world charm. Even though the living standard is now much higher, there is electricity, water, and better transportation. But I was looking for some of the old magic which I found here in Gunehar.

Till he was a 15-year-old, Schlichtmann went to different schools in India, went back to Germany for college, studied documentary filmmaking, and worked for a while in Cambodia, but his fascination with India never ended.

In 2008, he moved to India for a year on his way back to Germany, but has been here ever since.

I have always been very interested in the arts and have tried out certain art forms myself – painting, writing, and filmmaking etc.

The importance of going rural

What adds to the importance of the festival, apart from the fact that it utilises the ‘old world charm’ of a village setting is the fact that it remains unaffected by the cosmopolitan gallery-art market scene. “The event takes everybody — whether villager or city dweller, illiterate or art educated – at equal face value. I believe arts, especially conceptual arts, can transcend boundaries and Shopart Artshop is my attempt to prove this.”

When Schlichtmann curated the first edition with 13 artists, who could relate to the village and yet remain contemporary in their work, he was told that the idea would “never work.” “People in the cities feel privileged compared to villagers and also believe they know more than villagers do, even about village matters.”

People said that villagers don’t understand contemporary arts and that art was ‘wasted’ if held in such a setting. To me, though, art has to find that ‘common ground’ between different worlds and perceptions to be relevant, and with the excellent response of the batch of artists we had for the first edition, it was practically proven that this is possible if the whole process of creating art is open to all.”

Transparency is the reason that for this edition, artists were told to integrate elements from the local culture – painting, music, fashion, food – into their artwork. “Any one from the village who wishes to be part of it just comes ahead and starts helping. This is because, even if they often don’t understand intellectually this or that concept, they still feel that the whole thing is for and from them. The main thing is that everybody is included.”

Artists, therefore, do not operate in isolation from the village and the villagers, but rather are encouraged to engage with ‘hosts’ as much as possible. New bonds and relationships are formed across many divides, giving everyone who touches the project and is touched by it new thoughts and emotions about art and about the village as a venue for it. The resulting art works reflect the ability of artists to transcend boundaries between rural-urban, traditional-modern, and national-global.

Take Rema Kumar’s Gaddi Fashion show, for instance. This is a fashion line based on local costumes and created along with local women. Or Gargi Chandola’s Market Square Graffiti, which is a modern interpretation of Kangra Miniature Painting, being done in collaboration with painters of the Kangra Arts Promotion Society. While Schlichtmann was working on his own in the first edition, internationally reputed artists like Ketna Patel and Puneet Kaushik have come on board as co-organisers, and he is confident that the festival is only going to grow bigger from here.

Impacting villagers

The festival is about bringing rural and urban people together. It’s about bringing in contemporary artistic sensibilities and methods of conceptual arts as a ‘viewing method’ both to investigate what is happening in India’s villages and cities, which are often worlds apart as far as perceptions go. “We are taking the village at face value and as a legitimate space in the world. I think this is the main impact on the village, that they feel included, proud of this happening here. Of course it also earns them revenues, but primarily, it’s about inclusiveness and pride.”

With the Virtual Gunehar Project, which at this stage is a virtual, interactive walk through the village and the Art Shops on internet, the festival will evolve into a more complex structure covering not only future events but also other relevant matters related to the development of the village in future.

Schlichtmann also runs a restaurant and a four-room mud hotel in Gunehar. All his ventures are complimentary of each other and follow the same principle: to grow slowly and sustainably, to be inclusive and to be non-destructive of local culture and environment. “I get involved in village affairs mainly on a psychological level, by just being one of them. When there is an opening, like recently someone offered me his house to restore it in traditional style, I jump at it.”

The real challenge

I realise that everything one does, to remain successful, must be self-sustainable. As an entrepreneur, I know we have not reached that stage yet: the stage when I can walk away and everything will work as it should.

While artists have been willing to move out of their comfort zone and engage fully with the concept, getting sponsorship fund is the real problem. The only money that could be raised was through crowd-funding and that too, a meager 25 percent of the total budget. “But, things are changing slowly and this time, I had much better conversations than last time with potential sponsors. Even this much is a great improvement from last time. Something like this is quite unique and it needs lots of time and patience.”

Apart from determination, optimism is indeed what will take this entrepreneur a long way.

(Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of YourStory.)