Neeraj Jhanji - the man who created a mobile social network in the '90s and sold his patents to Facebook

On a rocking boat on river Spree in Berlin during Tech Open Air, Neeraj Jhanji recalls the last 20 years of his life. Despite the loud electronic music pouring from large speakers, he keeps talking as if he tried to store in the digital strongbox of a phone recorder the struggles and the achievements of a lifetime that the world has not yet fully acknowledged.

Throughout his life, Neeraj has fought hard to obtain what he wanted. This is how he won a full scholarship for an MBA in the US; and how he managed, in the late nineties in Tokyo, to develop ImaHima, the world’s first social network for mobile phones based on status update and location. This remarkable case of technological innovation, however, probably took place too early and the social media wave in the early 2000s in the US flooded the world ignoring any existing player.

Match Point

Neeraj was born in New Delhi in 1971 and never left India for the first 23 years of his life. While growing up, he realised the perception of the rest of the world in his country was a little distorted. “People still thought French people didn’t brush their teeth and random things like that,” he recalls laughing. Neeraj loved to tinker with electronic circuits, read Fortune magazine and books about great entrepreneurs like Akio Morita, and after a while started itching to go see the world as it actually was.

However, when he tried to make it into a university in the US, his visa was rejected. His second chance came after his graduation, when his father brought home a copy of India Today. “It had a full page ad from the Japanese company Fujitsu announcing they were giving a $60,000 scholarship to one Indian for a Japan-focused MBA in Hawaii.” Initially, Neeraj was quite disappointed the scholarship did not offer a place in an Ivy League university. However, after losing his father suddenly a few months later, he decided to apply because that was his only chance to start an international career.

When he went to the Fujitsu office to get the form, an apparently inconsequential event changed his life forever. “The man at the counter refused to give me the application form because I hadn’t yet completed one full year of working experience as per the requirements. On my way out, I heard the phone ringing in another room and the steps of the man going to pick up the call. Another lady went to replace him at the counter desk, so I went back in and started it all over again.” Within the blink of an eye, Neeraj had his form and was running away with it.

A few weeks later he learnt he won the scholarship.

Japan

During his year in Hawaii, Neeraj finally had the chance to meet people from around the world, found out French people actually brushed their teeth, and was able to send half of his monthly stipend to his mother and two sisters. Once he finished his studies in 1994, he moved to Tokyo to work for Accenture as a technology consultant. Part of his job was reporting about the developments of the new internet industry, it was the time of AOL, Netscape and Yahoo and the future was promising. In his first year, he flew to the Silicon Valley 13 times to interview entrepreneurs and became witness of the emergence of a new digital industrial era.

After a while, the startup fever took over and Neeraj started to think of ideas to develop on his own. “The more I looked into it, however, the more I realised the key positions in the internet were already taken,” he says. However, he adds, “l was in Japan, where this mobile internet thing was getting a little interesting.”

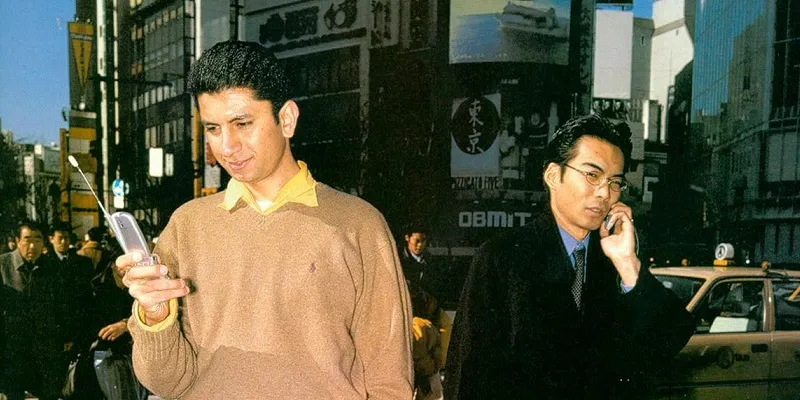

Shibuya

It happens that some places evoke inspiration for great ideas. In Neeraj's case, that was the Shibuya crossing in central Tokyo, one of the most crowded places on the planet. It may not be as romantic as a mountain valley, but it is the ideal place for observing social behaviours. In fact, the first episode that contributed to the development of ImaHima was when Neeraj saw a Japanese high school girl talking simultaneously on two personal handy-phones (PHS)—cheaper versions of cell-phones popular in Japan at the time. “Often young crowds’ behaviour represents the next trends, and that day I realised mobile phones were definitely the next big thing,” he says.

A few days later, Neeraj went out and wanted to meet someone for lunch but had not arranged with anyone beforehand. He recalls he had a cell-phone but it did not come in handy, “It was just a candy box with the antenna, a bunch of digits, two lines of texts, and no e- mail, camera or GPS. You couldn’t even text people who were with a different mobile carrier.” He was near Shibuya again and thought that with all those people around, it was highly probable that there was someone he knew nearby. That was the moment of realisation:

I know from my engineering background that cellular phones divide the city into cells and know how many cell-phones are in each area. So, I remember taking my phone out of my pocket, looking at it, and thinking that if it knows where I am, it knows where my friends are. Why doesn’t it tell me?

Neeraj had lunch alone that day, but when he went home he started sketching drawings of how the user interfaces of a location-based communication system for cell-phones could look like.

ImaHima 1

The main reason Neeraj decided to leave Accenture to dedicate all his time to his project was that his girlfriend broke up with him. “For the first time, I felt I had nothing left to lose by deciding to be an entrepreneur,” he says. He had very little savings but many good friends. One of them even offered $10,000 to back him up in the first phase of his venture and told him to make his crazy idea happen.

Now Neeraj was alone with his iMac in his room. “The first thing I realised was that I had no negotiating power with big mobile carriers and they would not share cellular location data with me,” he says. To better explain why, he adds that in the following years NTT DoCoMo even rejected Google to be part of their phones. “So, I was nobody. I was compelled to think of something different based on self-declaration, namely conveniently telling my friends where I am, rather than through an automatic system like GPS that tracks you. In fact, it was better because if you make it self-declared you can lie. You can say you’re here, but you’re there. Or you can even say where you’re going to be and what you are going to do, which a GPS doesn’t know,” he adds.

The second challenge was creation. Neeraj learnt programming computers before the internet era, but now the world had changed, “Now people are building web applications with PHP, MySQL, and tools I didn’t know,” he exclaims. He spent months looking for a CTO without much success, and one of the potential partners even opposed the name ImaHima (‘are you free now?’ in Japanese).

After months, nothing started so Neeraj set a deadline for the product to be live on December 15, the day of his 28 birthday. It was already end of November and he was alone.

Upon suggestion of his ex-girlfriend, he decided to develop ImaHima himself. After 14 days of non-stop work and sleepless nights, ImaHima came together. “In fact, it was just sticking together enough to make it to the deadline,” says Neeraj. On the 14, he filed the patent in the US and on the 15, he threw a big birthday where he showed all his friends his results. They loved it.

Users

The second tricky part was to market ImaHima. He tried to go back to Shibuya with some stickers and a phone to give people a demo but it did not work out. His alternative solution was at the edge of questionability and geniality. He says, “I had to come up with something and I am not sure what I did was right, but I needed a way to get the fire burning and this was the spark.” At that time mobile email addresses were created combining the user’s mobile phone number, the ‘at’ symbol, and the domain of the mobile carrier. Moreover, Neeraj explains,

Usually the phone numbers sold in a week change only in the last four digits. So, I created a computer program that would generate emails to hit those last four random numbers. Basically it was spamming but people liked it because nobody had thought about phones in terms of location before!

Users started increasing, but the real boom happened a short while later when ImaHima was featured on TV. “A presenter from a programme called Tonight 2 went to Shibuya, and before the ad break he announced he would try to meet two women through ImaHima.” The audience did not wait to see if it worked. “During the break everybody’s hitting my website,” exclaims Neeraj, excited as if the event was happening now. In the following weeks the traffic increased so much, he had to switch off features to prevent his servers from crashing.

ImaHima 2

Soon ImaHima attracted interest. Yoshiatsu Kitagawa, his former boss at Accenture, joined and soon the platform conquered half of the one-million user market in Japan. Within a year the company raised $3.7 million from AOL-Time Warner, a VC firm, and a bank. The fundraising happened quite fast because, Neeraj explains, he wanted to pay Yoshiatsu’s overdue salaries. The events that followed, however, proved the world was not yet ready for ImaHima.

First, Neeraj hired Infosys to build the next version of ImaHima.

I wanted to give a different example for Indian youth. I wanted to show – and still want to prove – that the right way is innovating with your own brand and product based on your own learning. And that’s why I think travelling and direct experiences are important. I don’t believe that one should go to the Infosys of the situation for directions too much. But I needed to quickly train an army of engineers in mobile technologies and I had some money, so I hired Infosys.

The second thing Neeraj did against his will was to create a paid model of his mobile website. “ImaHima was free and it could still be free. But when I tried to monetise with location-based ads nobody was willing to pay for that. I went to companies, brands, cinema chains and said I know the location of users and their friends in real time, and what they want to do. I thought it could be very interesting. I mean, how better can advertising get?” But he had no luck and with the pressure of monetising ImaHima, he was forced to introduce the paid version.

Finally, NTT DoCoMo started pressuring for more control over the features of ImaHima. “The worst happened when they told me that to allow someone to add a friend on his social network, he needs to put in the other person’s birthday date as verification that he knows them. Are you kidding me? I wanted to make this simple for people to meet each other and be new friends.” Later, NTT DoCoMo prevented ImaHima users from other mobile carriers from interacting with their users. Neeraj was at wit's end. “How can a social network work if you keep people separate,” he wonders.

Outside Japan

After a while, Neeraj felt too suffocated and decided to explore different markets. He tried with Europe and launched an SMS-based version of ImaHima (very similar to what early Twitter would look like) in Switzerland, but it had scarce success. “Using a social network over SMS is a little bit tricky. You need to know the commands and the short codes and it’s not really as usable as a mobile website, let alone an app,” he explains.

He looked at the US, but he did not even try to venture it. “In the US as well, the inter-carrier messaging was not allowed. Plus, at that time you’d pay to receive a phone call, so people would keep their mobile phones switched off and only use it for emergency calls,” says Neeraj, making clear it was a good idea to avoid that market.

It was the early 2000s, Neeraj had a revenue of half a million dollars, and came to the conclusion the mobile ecosystem was not there for him. He ventured into other related businesses, which he exited successfully, and let the first version of ImaHima run freely. “It had a dance form of its own,” says Neeraj staring into space, his glance shining with pride and love.

Epilogue

Neeraj’s last project with his former mobile carrier partner was in 2002. “NTT DoCoMo in partnership with AOL Japan offered a downloadable application feature on their handsets called iAppli,” he recalls. At the time, instant messaging for desktop was very popular, but Neeraj wanted to create one for mobile phones. “I added to my location-centred status update service an instant messaging feature using iAppli and I created the world’s first mobile chat app” he says. It was eight years before WhatsApp’s first release.

In 2006, ImaHima’s servers crashed badly and Neeraj took the painful decision to shut it down. A few months later, he received a call from a man in Israel who was interested in buying it.

Around that time, the great social media boom happened. Neeraj takes a big breath and gives his perspective on the link between it and the location-based services and status updates for mobile phones introduced by ImaHima.

One of the earliest social networks was Dodgeball, created by Dennis Crowley, who later will also start Foursquare. He was a student of NYU who did research on ImaHima. Shortly before that, ImaHima started attracting international attention and Megan Smith [US Chief Technology Officer, former Google] was interested. Later at Google, however, she bought Dodgeball, which then became Google Latitude.

He continues, “Based on the idea of Dodgeball came Twitter, which is the new ImaHima. Later in 2007, Apple launched iPhone, revolutionising the concept of mobile phone and mobile services; while Mark Zuckerberg realised status updates were really powerful. In fact, if you think about it without that there’s no Facebook newsfeed, without newsfeed there’s no stickiness, without stickiness you have no revenue and a $50-billion company.”

In this social media flood, Neeraj felt unfairly voiceless. However, the patents he had filed more than a decade before came to mind. “In the next few years I made sure the patents were around and eventually I found a respectable exit. In 2013, after two years of negotiation with pretty much all the big players in the industry, Facebook acquired the patents and that makes it a legit social network,” he says.

It is never over

But Neeraj is still running. Since 2013, he has been building Tinker and is launching AirMount.

The vision behind it is to create a direct network between nearby devices for all sorts of new applications. My dream is - maybe once again - to find something that creates a new industry. I’d be very lucky to get there twice, but I won’t stop trying.

To learn more about AirMount, check the website here.