Failure is the sibling of success: how you can tap failure as a strategic resource

As the year comes to a close, this outstanding book shows you seven approaches to frame and harness past failure as a source of resilience.

You have a lot to gain when you embrace failure as a means to generate learning, growth, and innovation, as explained in the insightful book, The Other “F” Word: How Smart Leaders, Teams and Entrepreneurs Put Failure to Work by John Danner and Mark Coopersmith.

John Danner is a management consultant with extensive experience in industry and government, and teaches at UC Berkeley and Princeton. Mark Coopersmith has worked in the startup and corporate sectors, and is a Senior Fellow at the Haas School of Business at UC Berkeley.

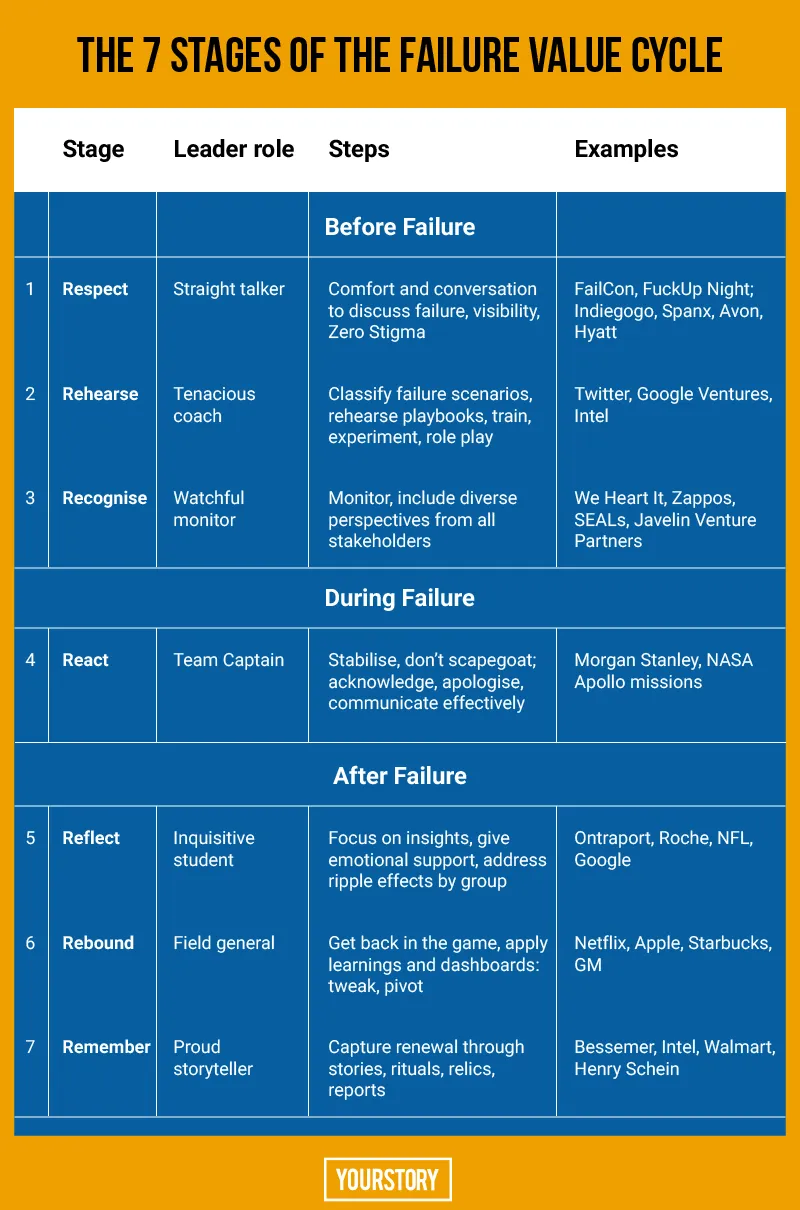

The core of the book is a seven-stage framework on how to harness failure, called the Failure Value Cycle: respect, rehearse, recognise, react, reflect, rebound, and remember. The 19 chapters are spread across 258 pages and are written in conversational style, with plenty of references, tools, examples and even humour. The online companion offers resources such as the Failure Value Report Card.

I have summarised some of my key takeaways below; see also my reviews of the six related books Adapt, The Up Side of Down, The Wisdom of Failure, Fail Better, Fail Fast, and Failing to Succeed.

I. Foundations: dealing with failure

The authors define failure as “mistakes and unwelcome outcomes that matter”. This includes intentional experiments as well as unpredictable external events. Some are caused by error and carelessness, others are the result of experiments and exploration, while still others are caused by accidents. They vary in terms of frequency, impact, and predictability.

Failure is personal and emotional, and can cause pain, fear, shame, guilt, depression, isolation, and embarrassment. In many organisations, the response to failure is denial, retaliation, scapegoating and a blame game; for some employees, it can even lead to job loss, denied promotion, damaged reputation, and stigmatisation. “Its memory lingers and deepens our fear of failure going forward,” the authors explain.

Many organisations penalise, ignore, rationalise or cover up failure. Failure is also referred to variously as defeat, collapse, mistake, loss, misstep, blind alley, bungle, flop, fiasco, mess, disaster, or screw-up.

But the authors argue that failure can actually be harnessed as a source of strategic advantage by startups, SMEs and corporates, provided leaders adopt the right perspective and create the right kind of culture. It is important to realistically confront failure and manager it rationally.

“Although no one likes to fail, truly successful leaders know how to turn a bad experience from a regret into a resource. They put failure to work, driving innovation, strengthening genuine collaboration, and accelerating growth in their organisations,” the authors begin.

“You can use the inherent power of failure to inform, teach, and inspire your organisation to lift its own level of performance,” they urge. Failure has subjective and objective connotations, depending on aims, standards, expectations, and frames of reference.

Some failures are losses while others are acceptable defeats. The definitions of failure can vary within the organisation, so it helps to begin by checking how you and your colleagues define failure, cite examples of past failure, and what lessons have been learned from them.

Though failure is everywhere, it is treated like a taboo. Failure is like gravity, the authors explain: it is ubiquitous, pervasive and even inevitable. It occurs across the board in products, ad campaigns, startups, investments, M&As, recruitment, sales, transactions, and projects.

“We not only live with failure, we live in it everyday,” the authors observe. Hence, dealing with failure begins with respecting it, just as we must respect gravity even as we learn to fly. Failure has also been likened to a vaccine that gives temporary discomfort before long-term success. Failure-savvy leaders condition themselves to be optimistic in the face of failure.

“Fear of failure is failure’s force multiplier,” the authors add. Fear of failure in the near term can lead to larger and even catastrophic failure in the long term. “Fear of failure greatly compromises an organisation’s ability to inspire, retain, reward, recognise, and replace great talent,” the authors caution.

Fear of failure in the face of the unknown stifles creativity, curiosity, initiative, aspirations, confidence, and the innovation spirit. Fear is failure’s strongest ally, the authors warn.

At the same time, the authors caution that one should not tolerate failure as an excuse for incompetence, negligence, carelessness, indifference or laziness. Fearlessness about failure should not be seen as a ticket for recklessness.

“How you deal with failures in your team is the acid test of whether you trust them, and vice versa,” the authors explain. Trust leads to better employee engagement, willingness to give critical feedback, ability to experiment, and capability to reflect on and rebound from failure along the way.

“In many ways, failure creates the ultimate proving ground for trust,” the authors add. This depends on how the organisation treats failure personally, professionally and collegially.

“Failure is today’s lesson for tomorrow,” the authors affirm repeatedly. Though understanding failure can be uncomfortable and unfamiliar terrain, it is a fascinating frontier. “Welcome to the family of the fallible,” they joke.

Failure isn’t the opposite of success, but its companion, sibling, and complement. Failure helps ground vision with reality, according to Google Ventures’ Joe Kraus. “Entrepreneurs who don’t have any fear of failure are dreamers,” he cautions; they usually do not succeed.

II. Failure in startups, SMEs, and corporates

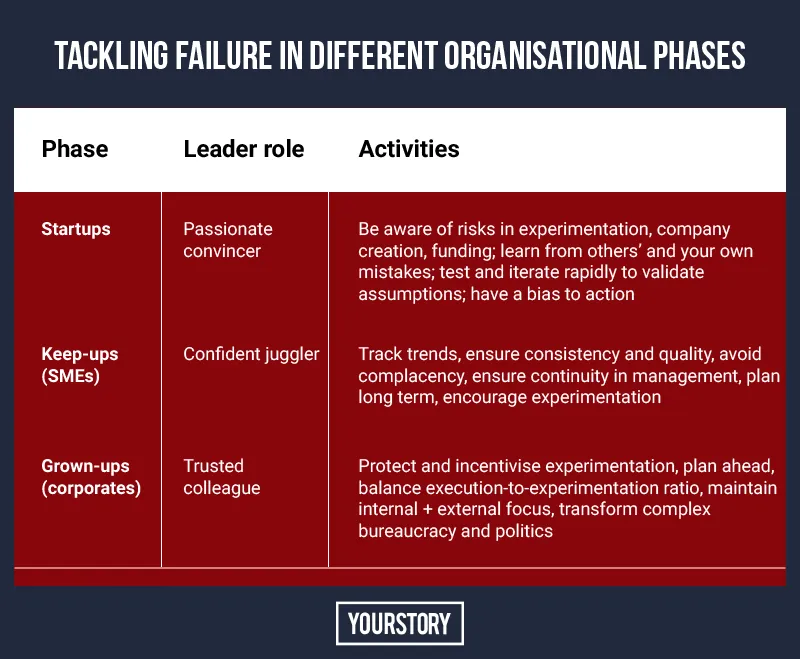

The authors explain how failure appears in different organisational phases and how they can be framed and managed (see my summary in Table 1 below). Each stage of growth has different connotations and consequences of failure, and leaders should prepare themselves appropriately in each context.

Startups by nature are fragile, and have a high rate of failure due to their experimental state. Startups spot opportunities in markets driven by tech trends or by spotting failures and gaps in the offerings of incumbent corporates.

There are many examples of failed forerunners and winning successors, such as Friendster and Facebook, and Altavista and Google. Yahoo outpaced AOL but was then passed by Google. Apple employees left to create Nest, which was then bought by Google.

The story of Instagram shows the power of a founding team to listen and learn from customer feedback; they focused only on the photo feature of the app Burbn, and the rest is history. Early e-tailers like Pets.com, eToys and WebVan closed down; timing, context and business models have changed, and Amazon is succeeding in many of their domains.

Unfortunately, many startups repeat the mistakes of premature scaling, dysfunctional chemistry, lack of capital, inadequate product-market fit, untested business models, and inability to cross the growth chasm.

In many countries, most businesses are SMEs, many run by families. Challenges arise in sibling rivalries and inter-generational tensions, but they also have the advantages of moderate risk-taking and long-term planning horizons. They can combine benefits of scale and agility, as compared to startups and corporates.

Many corporates began as confident innovators, but later become stumbling followers and even flameouts, as seen in the case of Sony, Atari and Wang Labs. The authors liken corporates to the “aircraft carriers of the business naval fleet.”

Though they can exploit global supply and distribution chains for economies of scale, corporates also have more to lose from disruption. They can thus become averse to risk and experimentation, unless they build the capacity for innovation and trust.

It takes commitment to create an ambidextrous culture of innovation as well as standardisation, instead of complacency, conformity, mediocrity and incrementalism, the authors explain. Large firms may be too big to pivot, but they can “arc” in a few years.

“Innovation is messy and unpredictable,” they add, showing how Hyatt Hotels had to push through change while introducing integrated rather than serial coordination for preparing guest rooms.

III. The Failure Value Cycle

The most useful part of the book is the authors’ framework called the Failure Value Cycle, consisting of seven stages for framing and managing failure (see my summary in Table 2 below). For each stage, the authors show examples of companies that succeeded in tapping the contribution of failure, and those that did not learn from failure.

(Stage 1) Respect failure: acknowledge its gravity

Many companies do not talk about failure internally, or in their annual reports. They prefer to “measure what they treasure,” rather than list failures and measure what they learnt from the failures. Ignoring, denying or defying failure is pointless.

Instead, leaders should set the tone by sharing their own stories of vulnerabilities, even with a touch of humour. Conversations should centre on What did you fail at today? to unearth insights to new approaches, as explained by Spanx founder Sara Blakeley. Language, comfort and candour in such conversations go a long way in boosting confidence in dealing with failure.

“Problems that need solving” (UAW) and “issues and challenges” (Avon) are better terms to describe failures. The field of science uses the frame of experiments and hypothesis testing to assess outcomes. Terms used in other industries are post-mortems (medicine), failure analysis (engineering), and rapid prototyping (design).

There should be a clear demarcation between no-failure zones and no-fault failure zones. Six Sigma works well in routinised domains, Zero Stigma works better in experimental domains. Failure should be de-personalised, the authors add.

Though Kodak had internal champions in digital photography and conductive films, it could not see past its original business model. On the other hand, Indiegogo openly shares what is not working, and asks employees for suggestions for solutions. Avon has a “Raise your hand” culture to encourage employees to flag issues.

(Stage 2) Rehearse: an ounce of anticipation is worth a pound of improvisation

The authors distinguish between two types of organisations: high-reliability (eg. airlines, hospitals) and high-resilience (eg. sports teams, startups, jazz bands). They call for rehearsals, checklists, redundancies on the one hand, and adaptability, flexibility, and simulations on the other.

Protection of “crown jewels” is a priority (eg. IP, algorithms, design, internal processes). Contingency plans need to be drawn up in case each of them is compromised. Scenarios of different kinds of challenges need to be enacted and even competed upon (“pre-hearsals”).

“Avoid the hearse, take rehearsals seriously,” the authors joke. In the words of Intel’s Andy Grove, “only the paranoid survive.” Organisations should chart out “failure horizons” that include black swan events.

For example, Twitter has extensive discussions on the successes and failures of its projects, and documents them for future reuse. UCSF Medical Centre conducts frequent rehearsals of emergencies.

(Stage 3) Recognise: pick up signals early

When failure is a constant companion, companies should devise early-warning alert systems about product defects, new trends, emerging startups, and changes in customer expectations, competitor offerings and regulations. Companies should “listen for the running water” like a beaver does, and repair existing dams or build new ones. Instead of focusing only on the status quo or static quo, leaders should address the future quo, the authors joke.

Unfortunately, many examples have shown otherwise: Target ignored early warnings about data security breaches, and GM ignored early signs of ignition problems. Many incumbents failed to see or change to new business models, as seen in the case of Kodak, Polaroid, Wang, Blackberry, and Borders.

(Stage 4) React: deal with failure

This stage unfolds quickly, and responses will depend on the scale, scope and type of failure. Companies should classify the types of scenarios, as seen in meteorology (hurricane categories), architects (buildings for different Richter scale earthquakes), and firefighters (number of alarms). Resist the knee-jerk reaction to scapegoat, be visible and available, acknowledge and apologise as relevant, and honour your honest failures, the authors advise.

Examples of good recovery include Johnson & Johnson (handling of the Tylenol tampering case in 1982) and Morgan Stanely (evacuation procedure during 9/11 attacks). Those who flunked at this stage include BP (Gulf of Mexico oil spill) and Lulemon Athletica (yoga gear complaints).

During the Apollo missions, NASA’s culture had a healthy respect for failure, and continuously rehearsed and reflected on its experiments. This culture unfortunately changed later, with people being ostracised for identifying risks, thus leading to the Columbia and Challenger shuttle disasters.

Interestingly, the authors point out that the phrase “Failure is not an option” was a Hollywood scriptwriter’s fiction from the movie Apollo 13, and was apparently not uttered by mission director Gene Kranz.

(Stage 5) Reflect: turn failure from a regret to a resource

It is tempting and sometimes easy to resort to finger-pointing, blaming and shaming in the aftermath of failure. While there should be high accountability, those who tried hard and failed despite their efforts should also be honoured, according to Severin Schwan, CEO, Roche.

Elizabeth Kubler-Ross describes five stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. This framework can be adapted to organisational failure as well. Mere acceptance of failure leads to incompetence and mediocrity; instead, there should be insightful reflection and corrective plans. Recovery and reflection go together.

The authors recommend different steps to handle ripple effects of failure in four groups: insiders (console and thank those directly involved), outsiders (admit and atone to customers and partners), audience (explain and reaffirm to media and investors), and colleagues (send the right signals, for example, don’t fire or abandon employees).

The authors cite Google and Ontraport as examples of companies that do not penalise failures or find fault with people, but instead focus on what went wrong rather than who did it. Open Innovation helps get outside inputs in ideation, as in the case of Boehringer Ingelheim (crowdsourcing algorithms in drug development via Kaggle). Asking others for help should not be seen as an admission of failure, but a quest for more creative solutions.

(Stage 6) Rebound: retake the initiative

The authors identify five responses to failed initiatives: tenacity (rivet rather than pivot), tweak (minor adjustment), turn (abrupt change), turnabout (fundamental reversal), or pull the plug. At this stage, failure lessons have been absorbed and incorporated in the next stage.

For example, Netflix initially bungled the launch and pricing of its parallel Qwikster service for DVD rentals. It apologised to customers, revised pricing, repositioned itself, and cancelled Qwikster to focus only on streaming. Such a comeback can take months or years, the authors explain.

(Stage 7) Remember: embed failure-savvy in your corporate culture

“The worst failure is repeating one you’ve already made,” the authors warn. Resilience, competence and confidence of a company in the face of failure need to be reflected in the way it embeds failure lessons in its DNA.

Failure and recovery stories are a rite of passage for startups. Such stories should be personal and authentic. Stories, and not just formal metrics, are a powerful force to shape a more failure-savvy culture, according to BCG’s CEO Rich Lesser and partner Roselinde Torres.

Failed products can even have talismanic value. The past should be honoured so as to create a lasting legacy across generations. The solvent WD-40 stands for “Water Displacement, 40th formula” – reflecting the past 39 failures. Ford’s Model T was named as the successor after earlier Models B, C and so on down the line. Rovio celebrates how it made 51 attempts before finding success with Angry Birds.

Bessemer Venture Partners publishes an “anti-portfolio” on its website, of companies that it passed up but went on to become successful: such as Intel, FedEx, Google, PayPal, and eBay. This admission was even done with a touch of humour, and takes guts and humility, according to the authors.

Walmart has a practice called “Correction of Errors,” which focuses on problems and solutions. Dental drug firm Henry Schein’s recovery from a painful computerisation rollout error in 1988 became a lasting story testifying its resilience, grit and organisation-wide commitment.

Intel made key rings of its flawed Pentium chip for its employees, with the inscription: “Bad companies are destroyed by crises, good companies survive them, great companies are improved by them.”

The Googleplex campus is built on the headquarters of former heavyweight Silicon Graphics, and has a replica of the T-Rex dinosaur as a reminder that once-mighty kings can become extinct as well.

IV. The Road Ahead

The book ends with description of a Failure Value Report Card that leaders can use to chart their journey to becoming more failure-savvy by tracking progress across the above seven stages. It has questions about conversations around failure, classification of failure types, environmental scans, core values, rehearsed protocols, internal communication, and failure lessons.

Graders should be drawn from the leadership team, as well as others inside and outside the organisation. There should be provision for anonymous feedback as well. General statements should be backed by specific examples where possible.

Corporate values of trust, teamwork, loyalty, creativity, and confidence are forged in the crucible of failure, the authors sum up. This is evinced at leader, manager and team levels. An innovative and ambitious company should be prepared to deal with the discomfort of failure, which is a natural step in venturing out of the comfort zone.

A fallible but failure-savvy organisation is marked by honesty (in discussing failure), curiosity (to forge ahead despite failure), pride (in overcoming failure), humility (in poking fun at one’s own failures), and engagement (no fear of ridicule in the face of failure).

“Failure is one strategic resource you and your team create every day. It has the power to teach you what to do and not to do next,” the authors sign off.