From passion to purpose: what we can learn about innovation from these 8 successful intrapreneurs

India needs intrapreneurship as much as it needs the startup movement to bring in fresh thinking at scale. Rashmi Bansal’s new book shares stories and lessons from leaders in a range of sectors.

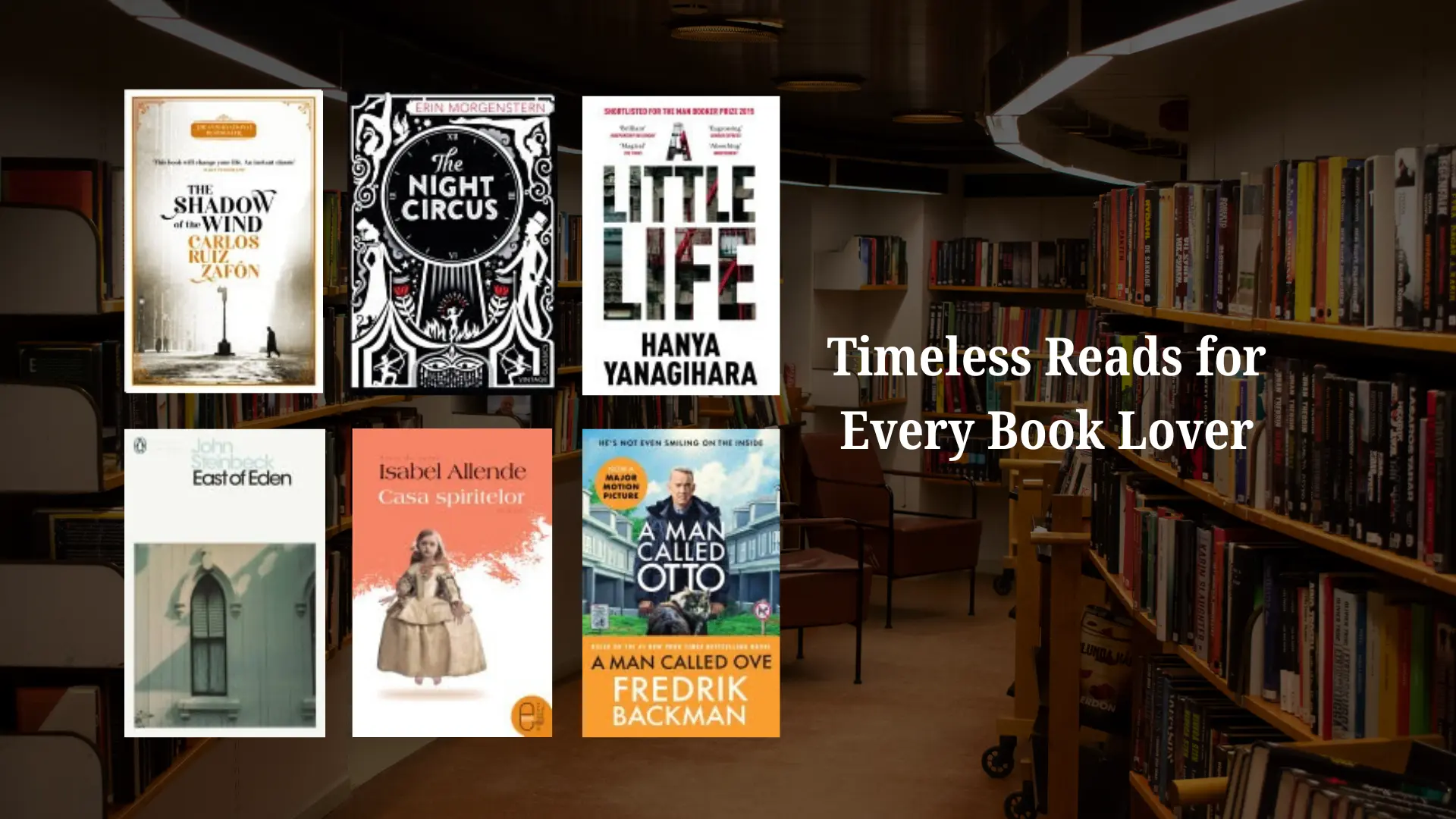

Innovative and perseverant leaders are found not just in startups, but large firms, government agencies, and the educational sector. Examples of eight such leaders are presented in Rashmi Bansal’s new book, Shine Bright: Inspiring Stories of CEOs who are Intrapreneurs.

Rashmi Bansal graduated from Sophia College in Mumbai and IIM-Ahmedabad, and is the author of a number of bestselling titles on startups. See my reviews of her earlier books on student entrepreneurs, social entrepreneurs, women entrepreneurs, small-town entrepreneurs, and slum entrepreneurs.

“When there is a sense of ownership – without being an actual owner – work becomes a calling,” Rashmi begins. The material is spread across 280 pages, and written in her trademark style with a liberal sprinkling of Hindi. The eight profiles are divided into three categories: srishti (creation), drishti (vision), and sewa (service).

Intrapreneur profiles

Amitabh Kant of NITI Aayog is an IAS officer who also loves art’s openness and power. He grew up in Varanasi and Delhi, and studied at St Stephen’s and JNU. He got selected for IAS and was allotted to the Kerala cadre.

Though initially “heartbroken” at having to work in a Marxist state, he came to accept that good work is possible and appreciated everywhere. Amitabh worked on initiatives such as financial provisions for fisher communities, and revitalisation of Calicut through removal of encroachments, launching the Malabar Mahotsav, and private sector involvement in financing the international airport (Kerala is the only Indian state with four international airports).

In the aftermath of the Babri Masjid demolition in 1992, Amitabh launched a community harmony art initiative in Calicut. Artists like MF Husain painted a 100-metre long canvas with images of peace and harmony.

The big game-changer was the branding of Kerala as tourism destination and promotion in international travel marts as “God’s Own Country” (coined by Mudra Communications’ Walter Mendis). Tourism was redefined through local roots, beyond the model of five-star hotels, eg. Alleppey houseboats for cruises, Wayand tree huts, Spice Garden in Thekkady, ayurvedic treatments beyond short massages. Data showed that tourism helped create 4.5 lakh jobs.

Amitabh was then transferred to Delhi, where he helped pull off the Ministry of Tourism’s integrated ‘Incredible India’ campaign. This replaced the earlier fragmented ‘Spiritual India’ and ‘Cultural India’ approaches.

“Kerala was a great learning experience. Because of that, I could hit the ground running,” according to Amitabh. The campaign included high-profile advertising overseas, partnerships with ASI for conservation of heritage sites, and involvement of international investors.

“Tourism must become a mass movement. It must be everyone’s business,” Amitabh emphasises.

He later moved on to lead other initiatives such as the Delhi-Mumbai Industrial Corridor Development Corporation, which includes creation of seven smart cities. As CEO of DIPP and later CEO of NITI Aayog, he was tasked with implementing the ‘Make in India’ and ‘Startup India’ programmes.

This included ranking states on ease of doing business, ‘name and shame’ rankings of the most backward districts in various states, using the ‘challenges’ approach to award tinkering labs to schools, and launching ‘grand innovation challenges’ to tackle tough problems.

Chitra Gupta, of Zeenat Mahal Sarvodaya Kanya Vidyalaya No. 2 (ZMSKV), transformed the low-performing government school for Muslim girls into an institution of excellence. She grew up in Cuttack, and pursued an MA. She moved to Delhi and taught in schools for well-off as well as poorer children, picking up administrative and finance skills along the way.

ZMSKV was seen as a “punishment posting” by some teachers, but Chitra took it up as a challenge. She used logical reasoning, empathy, and persuasion to transform the thinking of students and parents, and got the girls to participate in yoga and inter-school competitions for arts.

Jokes and stories were used as effective ways of communication with students, along with goal setting and systematic teacher approaches such as benchmarking with other schools’ practices. Open house sessions were held with parents to show the importance of education, such as enrollment in good colleges, better jobs, and financial stability.

Students were given open access to the principal, even to make complaints about non-performing teachers. Motivational sessions were held by inviting outside speakers.

Chitra’s efforts led to lower absenteeism, 100 percent pass rates in exams, and even merit scholarships for outstanding students. The school teachers themselves recommended Chitra for external awards. The story of ZMSKV has now become a success case study in the education community. Chitra unfortunately contracted TB and cancer, but has overcome the ailments.

Manu Jain, of Xiaomi, grew up in a joint family in Meerut, and studied mechanical engineering in IIT Delhi. He was active in dramatics and tech fests, and developed a strong belief in his capabilities. He joined TechSpan in Bengaluru, but didn’t enjoy working for a company where he could not meet its US clients.

Manu’s journey then led him to IIM-Calcutta, Tata Administrative Services, and McKinsey; memorable projects were improving productivity at landmines in Zambia. A college junior enticed him to come on-board Jabong as co-founder. Manu then moved on again, this time to Xiaomi, driven by his fascination with the smartphone.

New learnings and achievements were the power of crowdsourcing (eg. the idea for dual-SIM operation for WhatsApp; ‘copy OTP’ feature), social media influences on purchasing, cultivation of fan clubs, online-only launches, competitive benchmarking, channel differentiation, and broader outreach through offline stores. The company has expanded to wearables and smart TVs as well.

R Mukundan, of Tata Chemicals, helped transform the company from an industrial chemicals giant to an innovation-led consumer chemicals firm. Tata Chemicals was registered on BSE in 1939, and has its roots in Okhla Salt Works which was formed in 1926.

Mukundan grew up in Delhi and studied electrical engineering at IIT-Roorkee, where he was also active in SPICMACAY. He joined the Faculty of Management Studies (FMS), and later moved on to TAS. His initial work at a small bottling firm helped him master the full spectrum of operational activities.

Mukundan then became involved in the components segment of the Indica car project, and was exposed to a variety of MNCs and joint ventures. He then moved on to Tata Chemicals in Mithapur, where he helped restructure operations and reshape the culture towards accountability, ownership, international acquisitions, and infusion of fresh blood. He carried on the Tata legacy of community commitment beyond profitability.

Tata Chemicals diversified into agrochemicals and consumer products, such as Tata Salt, Swach water purifier, iShakti pulses, Sampann spices, and FOS sugar replacement (used for low-calorie sweets). There were also failures along the way, such as nano cement and nano fertiliser. The company exited the fertiliser business, which was driven by subsidy in the market.

Nitin Paranjpe became the youngest-ever CEO of Hindustan Unilever at age 46, and is now global COO at Unilever. With his DNA of a sportsman, he accepted that victories have to be won again and again. He grew up in Pune and Mumbai, studying at COEP and Jamnalal Bajaj Institute. He worked at L&T and then moved on to Hindustan Lever, working his way up from the role of sales manager to brand manager, regional manager, and director.

Nitin worked with products like Vim, appreciating the freedom and experimentation involved with the small brand. Other skills picked up were going beyond data to the power of observation and human connection. Setbacks along the way were a dealer strike, and the economic recession of 2008-09.

Inspiration came from interactions with late management guru CK Prahalad, who advocated the entrepreneurial mindset of having ambition and performance beyond available resources. This approach to visualisation of outcomes helped set audacious goals for distribution outreach, and partnerships with Tata Docomo.

Other approaches were willingness to be “reverse mentored” by younger employees to master social media. “We are a young country, so it’s important to understanding how young Indians think,” according to Nitin. This includes riding the wave of aspiration, and led to more high-end products at HUL. Nitin also believed in the power of Moral Quotient (MQ) in addition to IQ and EQ.

Pawan Goenka, of Mahindra Auto, grew up in Harpalpur and Kolkata, and studied mechanical engineering at IIT-Kanpur and Cornell University. He worked at General Motors, and then came across an ad calling on NRIs to find work back home. Upon invitation by Anand Mahindra, he returned to head their automotive R&D centre in Nasik in 1993.

Pawan rose through the ranks with successful products like Bolero, Scorpio, and XUV, learning how to negotiate with US and Korean players in the process and eventually becoming COO. The new mindset was product development with market research and the customer voice in the centre, and developing world-class products.

Pawan then drove the tractor business, and acquired a number of companies in Italy, Turkey, and Korea. A moment of pride was setting up a manufacturing facility back in Detroit. He became active in industry bodies like CII as well.

Harish Bhanwala, of NABARD (National Bank for Agricultural and Rural Development), grew up in a Haryana village, and studied at the National Dairy Research Institute. Inspired by the MNC lifestyle of his brother-in-law, he joined IIM-A; but his journey would take a different direction, to NABARD.

Harish learnt a lot even in positions where he was not a decision-maker. He learned to value the importance of people connections, to be sensitive to the plight of poor citizens, and to appreciate the power of self-help groups (‘social capital formation’). He encouraged employees to keep themselves updated on business trends, and take interest in their work beyond just showing up in the government office.

Harish took pro-active decisions such as offering banking services during the move to CNG in Delhi, issuing credit cards to employees, setting up a micro-irrigation fund for farmers to embrace precision farming (‘more crop per drop’), and implementing digital workflow for SHGs. He urged bankers to think more like social entrepreneurs than counters.

Vineet Gautam, of Bestseller India, is a Punjabi who grew up in Kolkata. He started off briefly with an engineering college in Maharashtra, but switched to hotel management. He worked at Nirula’s, Domino’s Pizza, CCD, Wills Lifestyle, Idea Cellular, and Benetton, making a mark as a committed manager willing to listen to employees, and picking up IT skills and data insights.

Vineet finally moved on to Danish firm Bestseller (with brands like Vero Moda), with an ambitious multi-channel launch campaign in Mumbai. Learnings and initiatives at this stage were the importance of storytelling to build brands, accessibility of managers to all employees and customers, enabling customers to get involved in modeling activities, innovating styles for Indian tastes, and implementing best practices beyond retail.

Advice to managers and entrepreneurs

Each chapter ends with advice for young entrepreneurs and managers. For example, visualising one’s future role and revisiting it every few years, helps develop a sense of perspective. Think big, but start small and move in steady steps.

It helps to follow one’s own pace, without worrying if peers have gone ahead; work should be for one’s conscience, even if there is no appreciation from others. Motivation can be intrinsic, and need not be driven from the outside.

Learning from peers and mentors helps achieve extraordinary heights of leadership, all the way to CEO. Leaders succeed through teams, whose dreams are shared and values are aligned. Leaders serve as the glue, cheerleader, and orchestrator of such expert teams, and should keep everyone informed of key decisions.

Smart work is as important as hard work. An active mind works best in a physically-fit body. Successful product development calls for deep involvement, which cannot be outsourced. There will be inevitable failures and setbacks, but it is important to learn the lessons, ignore naysayers, learn to work with a new mindset, pick future battles carefully, and move on quickly.

In sum, important values and qualities for the long haul are perseverance, overcoming initial inertia, humility, teamwork, commitment, consistency, excellence, integrity, passion, and positive energy. Ultimately, what leads to success and happiness is a sense of higher purpose, the joy of being a pioneer, openness to new ideas, enjoyment of work, and innovative and even disruptive thinking.

(Edited by Teja Lele Desai)