The Messy Middle: How endurance and optimisation are key for success in the long run

Every storm better prepares us for the next, explains founder-investor Scott Belsky in ‘The Messy Middle,’ a compelling book for entrepreneurs.

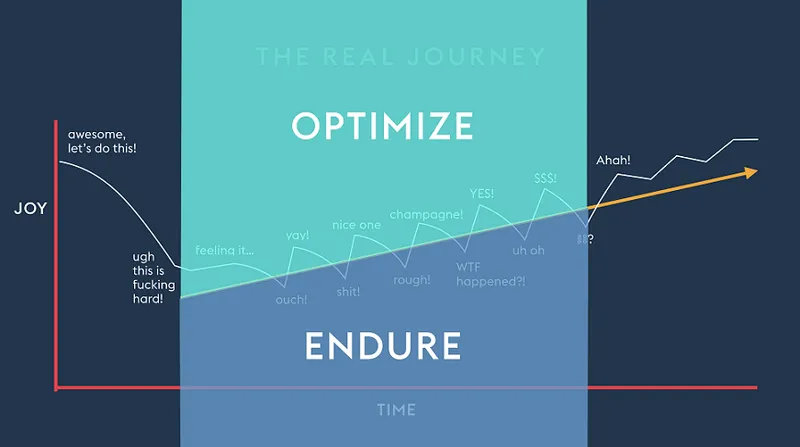

The startup journey is full of ups, downs and contradictions (though the ‘Black Swan’ coronavirus is in a league by itself). The joy of launch and the celebration of success are only end points in a long journey.

Though these events get written up the most in media, it is the long hard slog in the middle that is the hallmark of entrepreneurial success, according to the book The Messy Middle: Finding Your Way Through the Hardest and Most Crucial Part of Any Bold Venture, by Scott Belsky.

“You survive the middle by enduring the valleys, and you thrive by optimising the peaks,” Scott begins. “If you stay curious and self-aware, your intuition and conviction will be your compass,” he adds. Ups and downs constitute the rhythm of making, and indeed of life itself.

Scott Belsky is an entrepreneur, author, and investor. He is Chief Product Officer at Adobe, serves as a board member for startups, and is a Venture Partner at Benchmark. He was previously the founder and CEO of Behance, a platform to showcase and discover creative work (acquired by Adobe in 2012).

Scott is also the creator of 99U, Behance's thinktank and annual conference on the creative world. He is the author of Making Ideas Happen, and co-author of the 99U book series (see my book review of the title Make your Mark: The creative's guide to building a business with impact).

“The middle contains all the discoveries that build your capacity,” Scott writes, describing the endless surprises and disappointments in the middle phases. Sometimes the meandering journey seems like two steps forward and one step back – or even a completely wrong path. There is disappointment when there is lack of traction, recognition or significance.

Unfortunately, not all founders do a good job of documenting and reflecting on the insecurities, despair and self-doubts in this volatile middle. The stories and lessons in Scott’s book are therefore useful for anyone in the creative field – whether a startup, corporate innovator, designer, author or artist.

The material spans almost 400 pages, but could have done much better in terms of structure and design. Here are my key takeaways from the book; see also my reviews of the related titles The Creative Curve, Trillion Dollar Coach, Disciplined Dreaming, BlitzScaling, and No Shortcuts.

The Messy Middle (source: Scott Belsky)

I. Endurance

The author shares a number of anecdotes and tips on enduring the hard knocks of a creative journey. Navigating these ups and downs is what makes for not just drama and good stories, but a successful mission.

One must accept and learn to deal with uncertainty, resistance, friction and confusion. Self-awareness, commitment, originality, positivity, patience, and parallel processing are key for success.

1. Conviction

Strong conviction helps stay the course when the end is not clearly in sight, as shown by Steve Jobs’ legendary “reality-distortion field”. Originality should be nurtured and defended, even if it means being misunderstood, criticised, and called ‘weird.’

Clarity of perspective helps rally people around the mission, and make them believe that they are on the right side of history. The Eiffel Tower and Louvre Pyramid were initially mired in controversy and criticism, before becoming iconic landmarks of Paris.

2. Adaptability

At the same time, pivots and resets are hard but necessary, as shown in the eventual success of YouTube (originally a dating site), Twitter (initially a podcast network Odeo), and Instagram (which began as the game Burbn).

This calls for accepting the suffering or disappointment of starting all over again. “Strong opinions, weakly held” imply willingness to change in the face of better evidence and solutions.

3. Optimism

“Manufactured optimism” and “hacking your reality” help cope with long frustrating phases of no traction; after all, it is hard to run a marathon when you are hungry. “You must create your own rewards out of necessity,” Scott urges.

Even tiny wins should be celebrated, and milestones created. Short-term rewards can be satisfying and even addicting thanks to the dopamine rush, as described in the book The Entrepreneurial Instinct by Monica Mehta (see my book review here).

At the same time, one should not “sugarcoat a bitter pill” or blunt a blow. Employee morale must be gauged through regular meetings and even anonymous surveys. Hard truths must be shared when there are layoffs. Fundraising is a tactic, not a goal, Scott adds.

4. Resilience

When faced with challenges, it helps to compartmentalise them and deal with them separately, rather than feeling overwhelmed with day-to-day issues. Keeping focus and perspective is key, Scott urges.

“Friction not only reveals character, it creates it,” he explains. Learning how to cooperate in the face of adversity and disagreement is necessary for group survival.

Leaders should be able to turn around negative conversations into positive ones, and their enthusiasm should give energy to stakeholders. Scott cites David Wadhwani, CEO of AppDynamics, and Jon Steinberg, former president of BuzzFeed, as exemplars in this regard.

5. Self-awareness

“The only sustainable competitive advantage in business is self-awareness,” Scott emphasises. This involves jettisoning ego, understanding your own triggers and frustrations, seeking feedback proactively, and chronicling your journey. Cultivating curiosity, humility, and even spirituality are key, Scott advises.

Floodlights and spotlights each have their unique strengths. Asking the right kind of probing questions helps bring out new perspectives and refine product focus, as seen in the rise of Periscope and its eventual acquisition by Twitter. Past assumptions and sunken costs should be cast aside to get at the root of a problem.

6. Patience

Companies must build cultural and structural systems for patience, based on clear principles and infrastructure. “Amazon is perhaps the greatest corporate example of patiently executing a strategy over time,” Scott explains. This builds desire for long-term progress, and not just immediate returns.

Netflix is another example of a company that played out its strategy of online content delivery for over two decades, even in the face of ridicule. It eventually outlived early competitors like Blockbuster, but had to deal with slower consumer internet speeds in the early years.

“Progress takes time, even when you have the very best strategy, people and resources at your disposal,” Scott cautions. “The long game is the most difficult to play and the most beautiful one to win,” he emphasises.

Outsider perspectives coupled with determination are other ways to success, as shown in the rise of Airbnb and Uber. Their founders were not jaded by or accustomed to industry dogma, but had a strong opinion of what should change, Scott observes.

At the same time, not having insider skills means resilience is a critical trait. Startups are really “stay-ups,” according to Basecamp co-founder Jason Fried.

As companies scale, founders should guard against “corporate obesity” and lack of energy and imagination. Mobilisation can be achieved by working with the right types of people and depoliticising processes.

II. Optimisation

The author identifies three focus areas of optimisation: team (recruitment, culture, communication), product (vision, customer focus), and oneself (decisions, instincts, originality).

“You should be proud of what you’ve accomplished, but never satisfied,” Scott urges. Optimisation is about continuous improvement, and willingness to be surprised about what works and what doesn’t. Continuous testing applies not just to products but organisational processes and culture as well.

Become more efficient before you become bigger, Scott advises. This involves working with constraints and without expectations of large budgets, as exemplified by SkyBox. It made cheap satellites using off-the-shelf components, and was eventually acquired by Google.

1. People, culture, communication

People should be hired for their initiative, and not just education. “Initiative is contagious, expertise is not,” Scott succinctly explains. Passion, obsession, and proactive “can do” or “yes, and” mindsets are more valuable. Other traits to look for are courage, particularly in those who have weathered adversity.

Diversity in the workforce is an added asset, even if it involves bringing on board people who are talented but may come across as irritating or polarising. Having different points of view leads to creative sparks flying.

There should be a mix of dreamers and doers, artisans and business people. Disagreements and strife between opposing camps are inevitable, but should be channeled for better decisions and products.

“Creativity comes from unlikely juxtapositions,” says MIT’s Nicholas Negroponte. Scott cites his own early team at Behance as such an example. “Innovation happens at the edge of reason, and you can’t reach the edge with a team of similar people,” he adds.

A good leader is also a thought partner, mentor, coach, and advocate for employees. Empathy, integration, psychological safety, and real-time feedback are vital in this regard. Giving ‘stretch assignments’ helps push comfort zones, shake things up, and expand perspectives.

“One of the hardest parts of leadership is not getting attached to people,” cautions Anne Wojcicki from 23andMe. This is particularly so when it comes to firing people.

“A healthy culture built on stories provides the context and comfort everyone needs,” Scott explains. Even informal stories of initial meetings and food habits can become a part of “cultural knitting.”

Such “story-making moments” should be harnessed. “Each team has a few ‘culture carriers’ who are especially good at capturing stories and retelling them,” Scott observes. “Don’t underestimate the value of a story,” he urges.

Internal marketing and even merchandising is an effective tool. This applies to communications campaigns, nomenclature and infographics. Examples include Behance’s ‘Done Walls’ to celebrate completed projects as a way of marking progress. Displaying mockups also promotes alignment.

Founders need to master different types of inter-personal communication, depending on context. This varies from email to face-to-face conversations, formal sessions to informal outings, scheduled discussions to spontaneous chat.

Having a creative space at work is a key asset, as seen in companies like Apple which ensure that employees have a “daily encounter with beauty.” Pixar’s “town square” space encourages serendipitous idea exchange.

There should be a mix of process and flexibility in work. Processes should be more about alignment than imposition, and should be audited and revised as necessary.

“Knowing how to respect process while not letting it inhibit progress is one of the holy grails of management,” Scott emphasies. “Embrace best practices until you need to change. Then break them,” he advises.

“Delegate, entrust, debrief, and repeat” is a good approach to use for ensuring empowerment, responsibility, and accountability. Autonomy should be accompanied with quality control. Founders also need to harness the energy of “free radicals” or mavericks. They are great assets even though they may seem unwieldy at times.

Employees with conviction and strong gut instincts should be encouraged to ask persistent and even annoying questions that “bash inefficiencies and dumb practices” in the organisation, even if it risks upsetting someone. Time and effort should be spent on incremental improvements as well as big bets, moving pebbles as well as boulders.

Routine activities should be executed effectively, but should not lull one into complacency or a false sense of achievement. There are times to move fast, but there also times to slow down and work on perfection of product features and customer experiences.

Strategies and tactics of competitors should be welcomed and carefully understood, and not ignored, diminished, or copied. Competition validates market needs – it can also turbo-charge your initiatives and provide a sense of urgency, Scott explains.

“Time adds a value to creative work that cannot be replicated any other way,” Scott emphasises. Some of the best works begin as musings, side-projects, or something that was kept on the backburner, and then perfected over time.

When the decision is made to choose one set of actions and not another, false hopes should not be offered about the change in direction. “Declare the implications and chop off the rearview mirror,” Scott urges.

Ultimately, the core values, beliefs and practices should be internalised and become the “secret sauce” of a company, according to Ben Thompson, author of Stratechery.

2. Product

Companies often begin their journey with a simple, compelling product. As they grow, the product becomes complicated, and customers then flock to another company with a simpler product. These product waves are characteristic of many industries, Scott explains.

He classifieds products into two types: those that save time (eg. Google Maps, Uber, Slack) and those that spend time (Facebook, Snapchat). Many successful startups hunt and reduce friction; the challenge is to keep products simple as new customer bases are added. It helps to stay grounded in customers’ struggles and psychology in this regard.

“Take great pride in your product, but not at the expense of failing to see its problems,” Scott advises. “As soon as you are satisfied, you become complacent. Never be truly satisfied,” he urges.

“The creative process is a little dreaming, followed by endless editing,” Scott describes. Focus involves making tradeoffs. For every feature added, subtract another, he offers as a thumb rule. Ultimately, the best designs are almost invisible.

“Creative writing is a war between simplicity and possibility,” Scott says, drawing on examples from literature. “Focused creativity is more important than more creativity,” he adds.

It is important to understand power users (‘vocal minority’), new users, and potential users. Along the journey, it may also be necessary to kill earlier products and features. User community suggestions can help in this regard.

Disney has implemented this idea refinement process through three phases: generation, aggregation, and elimination. No-holds barred creativity is followed by an “idea bloodshed.” Walt Disney himself was described as having three personas: dreamer, realist and spoiler.

Where possible, new products should build on earlier familiar experiences and metaphors. Retraining consumers should be resorted to only if a new experience is the core differentiator, eg. SnapChat.

In the customer’s product experience, the “first mile” must be well crafted, and clearly address purpose, outcome, and next steps. This changes with new customer bases, eg. Twitter’s second cohort after early adopters wanted immediate access to news, just as if they were switching on a TV set.

In the early moments itself, the product must connect to deeper user needs of vanity, laziness and selfishness. For example, for online platforms, this can mean getting likes and friends as soon as possible, with short learning curves, and quick returns.

Effective hooks and taglines can pull customers in through the door. Demos and templates help users get started quickly and easily. Novelty and fun factors can also be attractors in some cases.

There are times for incremental improvements, but they can trapped in a “local maximum.” After some time, it may be necessary to reinvent and even disrupt oneself. For example, the digital experience has moved from the desktop to the mobile, and is now being augmented with voice and AR/VR as well.

Customer expectations and cultural norms are also changing fast. Tapping fresh talent and new consumer insights helps create regenerative forces and overturn prior assumptions, Scott advises.

He also observes that many entrepreneurs fail because they are too focused on a topic rather than a problem. Developing deep empathy and insights of consumers helps nail a problem, eg. SnapChat understanding teenagers’ needs for ephemeral content for social reasons.

For business success, it is important to classify customers into willing, forgiving, viral, valuable, and profitable. Product rollout should be fast, but not at the cost of losing empathy and insights of customers.

The story of the founder, company, and product drive the marketing narrative. Even introverted founders need to hit the street and start selling (see my book review of The Introvert Entrepreneur by Beth Buelow).

“Brand-product fit” is an important consideration in this regard, and includes the offerings, features, outcome and even name and logo. In cases where the product is a platform, a stewardship role should be adopted based on transparency, fairness, and meritocracy.

“Best to market” may lead to more success than “first to market,” Scott advises. Soft launches are better for early-stage startups, while a press-worthy launch is better suited for high-profile firms like Apple. Apple is also known for cultivating a sense of mystery and magic in its engagements.

In terms of prioritisation, it helps to rank features in terms of impact and effort, and focus on those which have highest impact with least design or development effort. Engagement drivers should be distinguished from interest drivers.

3. Self

Founders must learn how to plan, but be prepared to deviate from it based on circumstances and gut instinct. Projects should be chosen based on the new skills and relationships they bring to the table for entrepreneurs and artists. It is better to be a ‘satisfier’ than a ‘maximiser,’ and learn how to say no rather than suffer from FOMO or confusion.

A sense of timing strengthens with experience, and helps decide when to go from small steps to a big leap or pivot. Good leaders can do this even if the decision is unpopular, can cause discomfort, and involves sunken costs (of money, energy, time, reputation).

Founders must listen to advice but make the final decision based on their own analysis, even if it means not following advice or external reviews. Scott points to iPod’s early market criticism as an example. Many successful inventions were unpopular, misunderstood or underestimated in their earlier days, so it should not deter you if people dismiss you as crazy.

Instead of having dashboards of dozens of metrics, Scott advises focusing on only one or two core ones, eg. number of client-professional working pairs in the early days of referral network Prefer.

Metrics will change over time and must be audited and updated. Care must be taken while interpreting the context, integrity and relevance of data points. For example, Square decided to stick to its ‘finger flick’ signatures as part of the brand experience, even though competitors removed the need of signatures for smaller transactions.

“Great inflections are the result of instincts for what will serve your long-term goals; they’re about feeling, not thinking,” Scott emphasises.

It helps to listen to alternative viewpoints, vocal critics, and even the ‘ignorance’ and naivety of new people. Openness leads to new insights, Scott urges. In creative teams, it sometimes helps to hand off ideas and let others shape it.

Art, science, and business play different roles in the creative journey. “The beginning stages of a business are more art than science,” Scott explains. New ideas may feel strange and uneconomical, and not scale well.

“The greatest innovations in an industry are strange and artlike before they become the new standard,” he observes. “The best brands are profitable from their science yet known for their art,” he adds.

Many successful leaders are known for their quirkiness and obsessive attention to detail. “By preserving the art in your business, you give it a soul that people connect with,” Scott advises.

Effective leaders have a sixth-sense-like intuition based on their networks and ability to filter signal from noise. They have optimised routines, but also break them on occasion; they learn from random encounters as well.

Scott advises disconnecting and taking off-days or off-hours to get away from ‘reactionary workflow.’ It restores energy, refreshes the imagination, and strengthens deep thinking. It helps wondering and wandering, and allows for new questions and curiosities to hold.

Humility rather than a sense of superiority keeps you grounded; over-confidence can lead to destructive behaviour. Too much publicity can lead to numbness. Scott observes that despite his enormous business success, Jeff Bezos is known for his insatiable curiosity and prefers asking questions rather than being the centre of attention.

III. The Finish Line

The book ends with some intriguing insights on what happens at the end of the creative journey, after the messy middle. If a startup exit is involved, it calls for a different mindset and skillset.

“A great founder isn’t necessarily a great finisher. The last mile is a different sport,” Scott cautions. It may involve acquisition by a large corporation, which calls for understanding dealmaking via advisors and coaches.

Drawing on his experience of selling Behance to Adobe, Scott recalls how he sought advice from other entrepreneurs and investors. “The last mile is not to be travelled alone,” he explains; it involves assessing impacts on co-founders, employees, partners, and customers.

The creative challenge in the later stages of the journey is to still retain the “openness, humility and brashness” of earlier stages, which can even involve cannibalising earlier products. “To be done is to die,” Scott says, emphasising the importance of regeneration and reinvention.

Scott cites Warren Buffet as a great example of someone who is self-reflective and even self-deprecating. He has insatiable curiosity, willingness to learn, and ability to change long-standing beliefs. Books give him knowledge, which he says builds up like ‘compound interest.’

Unfortunately, a startup may need to shut shop if things don’t work out. “If you can’t end wonderfully, end gracefully,” Scott advises, drawing on examples of founders’ closing notes to investors. “If you handle it well, failure is merely a step in the right direction,” he says.

“The most humbling part of creation is that you’re never truly done,” Scott explains. Many creative people move on to other ventures. For example, in later stages, one may become an advisor to non-profits or educational institutes, with a very different culture from a startup.

There the role is to be more of a contributor than a maker. However, one must also realise that there is more to life than one’s company or work, and find joy in hobbies, family and spirituality as well.

In sum, the book offers a wealth of stories and insights for founders, despite its rambling and sometimes repetitive style. The book is packed with insightful quotes, and it would be fitting to end this review with the sample below.

Invention requires a long-term willingness to be misunderstood. – Jeff Bezos, Amazon

Startups win by being impatient over a long period of time. – Aaron Levie, Box

A good team does a lot of friendly front-stabbing instead of back-stabbing. – John Maeda, RISD

The best way to complain is to make things. – James Murphy, LCD Soundsystem

What distinguishes great founders is not their adherence to some vision, but their humility in the face of the truth. – Paul Graham, Y Combinator

Product-market fit is a journey, not a destination. – Taylor Barada, Adobe

Telling the truth is hard work and requires skill. – Ben Horowitz, Andreessen Horowitz

What stands in the way becomes the way. – Marcus Aurelius

The idea of being born ‘weird’ means you have a gift. – James Victore

A committee is a group that keeps minutes and loses hours. – Milton Berle

If you’re immersed in a context, you can’t even see it. – Alan Kay

Knowing when to ignore your experience is a true sign of experience. - John Maeda, RISD

Outlasting is one of the best competitive moves you can ever make. – James Fried, BaseCamp

Grit is living life like it’s a marathon, not a sprint. – Angela Duckworth, ‘Grit’

(Edited by Teja Lele Desai)

![[YS Exclusive] Inside the home and heart of Ratan Tata, the man behind one of India’s oldest business empires](https://images.yourstory.com/cs/2/2d86ed30b28211e8b2e7114aea10c711/RatanTata021575874425629png?fm=png&auto=format&h=100&w=100&crop=entropy&fit=crop)

![[Matrix Moments] To sell or not is the big question for startup founders, says Avnish Bajaj, Matrix India](https://images.yourstory.com/cs/wordpress/2013/11/exit.jpg?fm=png&auto=format&h=100&w=100&crop=entropy&fit=crop)