Beyond trends and talent: how to master the four laws of creativity for business success

Consumption, imitation, creative communities, and iteration are the four laws of creative success, as explained in this insightful new book.

In a globalised, digitally connected world, the power of creativity is more important than ever before. In domains ranging from startups to movies, there are myths and misconceptions about what constitutes the right formula for success.

Frameworks and tips for creativity are well-described in the new book, The Creative Curve: How to Develop the Right Idea, at the Right Time, by Allen Gannett. It provides a wealth of examples of these principles in action, ranging from Netflix and JK Rowlings to the Beatles and even Ben & Jerry’s ice cream.

Allen Gannett is the founder and CEO of TrackMaven, a software analytics firm whose clients have included Microsoft, Marriott, Saks Fifth Avenue, Home Depot, Aetna, Honda, and GE. In addition to patterns in marketing, his “lifelong geekery” has led to years of research into creativity, culminating in this book.

The 10 chapters are spread across 270 pages, along with 27 pages of references and footnotes. In addition to citing academic and business books, the inclusion of excerpts from actual expert interviews makes the material informative and entertaining at the same time.

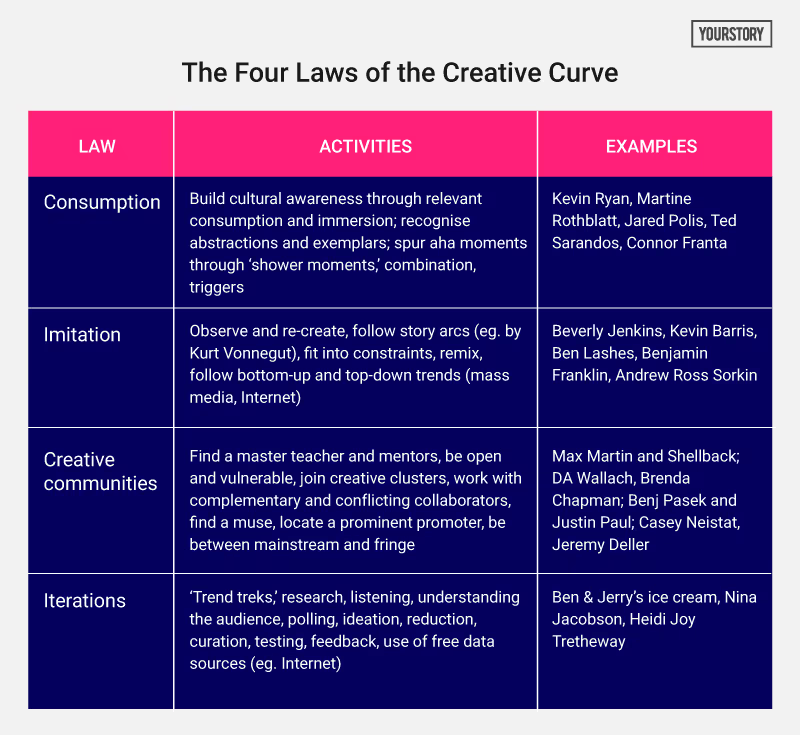

Here are my key takeaways from the book, summarised in the following sections and in Table 1 (see below). Also check out my reviews of the related books How to Get to Great Ideas, The Other Ideas, Ideas are Your Only Currency, Show Your Work and The Innovative Mindset.

Creativity myths debunked

Over the centuries, creativity has been confused with divine intervention, spiritual possession, solo acts, mad/neurotic/manic genius, lightbulb moments of sudden brilliance (‘aha’ moments), and serendipitous occasions. It is also a myth that success follows easily from inspiration, Allen counters. On the other hand, artists were also confused as mere craftsmen during medieval times.

Paul McCartney’s hit songs like Yesterday were actually the result of hard, grueling work, on top of influence, ingestion and reinvention of other music. Mozart was a practitioner of intense and diligent effort.

Hard work, cool offices, plentiful whiteboards, open brainstorming, and inspirational influences are also not sufficient for creativity. True understanding of creativity comes from neuroscience and long-term research on creative careers, market data, and creative communities, Allen explains.

For example, the “aha moment” actually involves connections that are being forged in the subconscious brain; they seem like a magical flash when they are passed on to the conscious brain, but we are just unaware of the prior processing. Such connections create powerful emotional reactions, and happen during different activities (eg. showers), through combination, or triggers (eg. seeing a crossword clue on a signboard).

Talent and genius

The divergent thinking of creative thinkers is measured by the number, quality and originality of their ideas. It is not just the number of hours of practice (eg. 10,000 hours) that matters, but the intensity of engagement and the mental models created. Structured, purposeful practice should also be accompanied by clear feedback. In the long run, continuous learning improves brain plasticity

For example, accomplished painter Jonathan Hardesty studied for years under a master teacher in his studio (the atelier model), and regularly posted his work online (ConceptArt.org).

“A person’s work has to be accepted by other people to garner the creative label, and by even larger numbers of people for a person to be labeled a creative genius,” Allen explains. He draws on the work of professor Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (author of the influential book Flow) to show that creativity is shaped by domain expertise, market timing, industry gatekeepers, and persuasive power.

The creative curve

Creativity is defined as something novel and of value to a group of people who find usefulness or importance in that product. Market appeal involves a judicious mix of the novel and the familiar.

The creative curve (shaped like a bell curve) of preference plotted against familiarity defines how products go through trend phases of novelty, popularity peak, overexposure, and decline. More specifically, Allen names the phases as fringe interest, sweet spot, point of cliché (peak segment), follow-on failure, and out of date.

This curve applies to individual as well as group preferences. The sweet spot involves the optimum mix of preference and familiarity, safety and surprise, similarity and difference.

Early adopters of products also tire of them earlier than others. Timing is critical – adding too many new features to a new product may confuse or overwhelm users, or fail to resonate with them.

For example, social media platform CampusNetwork was launched just weeks before Facebook, but had too many features, some of which were ahead of the time; this made users uncomfortable with having to make “too many leaps at once.” Facebook, on the other hand, added more functionality as users learned successive features and became familiar with them.

“What is called creative genius is really the ability to understand the mechanisms of the creative curve and use it to engineer mainstream success,” Allen explains. The Beatles started off with pop, then experimented gradually with psychedelic effects, and returned to pop basics after the experimental sounds became cliched; the rise and fall of their experimental effects reflects the bell curve.

In an important clarification, Allen distinguishes the creative curve from the technology adoption curve, in which technology adoption goes from zero to 100 percent. In the creative curve (based on exposure and not time), ideas start off as popular, reach a peak, and then drop off and become unpopular again.

The second half of the book focuses on Allen’s 'four laws of the creative curve,' which include consumption (familiarising oneself with a chosen field), imitation (learning from successful predecessors), creative communities (finding collaborators and a support group), and iterations (data-driven refinement of ideas). See my summary in Table 1 below.

1. Consumption

Voracious, intentional consumption of relevant content, along with expression of opinions about it, leads to becoming an influencer or tastemaker. Immersion in and exposure to these raw ingredients helps identify where products lie on the slopes of the creative curve, and makes it easier to develop prototypes and exemplars for new categories.

This pattern-recognition skill helps creative people become successful serial entrepreneurs across industries, such as Kevin Ryan (Business Insider, Gilt, MongoDB, DoubleClick), Martine Rothblatt (Sirius Radio, United Therapeutics), and Jared Polis (ISP, BlueMountain Greetings, ProFlowers.com, TechStars).

Ted Sarandos consumed countless hours of video content in his teens at Arizona Video Cassettes West in the 1980s, and developed an understanding of audience tastes and preferences. Regarded as a “human recommendation engine,” he is now chief content officer at Netflix.

So also, painters frequent art exhibitions, chefs travel to food shows, and songwriters listen to music. Allen recommends spending 20 percent of one’s time consuming relevant material in the chosen domain to develop an intuitive understanding of trends and success factors.

The “ever-churning blender that is the internet” is spawning new opportunities for becoming an expert, such as YouTube celebrity Connor Franta. He was an early consumer and creator of online videos at a time when no rules or standards for success were set.

2. Imitation

The second law of creativity is imitation of top-down or bottom-up creative successes. This helps create the baseline of familiarity with domains and audiences, and internalise the creative patterns of masters.

This step can involve following story curves that map fortune with time, as defined by Kurt Vonnegut: such as man-in-hole (good fortune, trouble, getting out), or Cinderella (rise from ill fortune, fall, rise to supreme happiness).

Benjamin Franklin refined his writing skills by observing and re-creating articles from The Spectator. Beverly Jenkins found a niche by creating historical Black romance, filling the gap in a field largely dominated by white characters.

“The Internet has been instrumental in transforming the power structures of creativity,” Allen explains. “What we’re seeing on the Internet is real-time culture creation,” he adds. It democratises content access and creation, and opens up new opportunities for influencers and entrepreneurs.

For example, Reddit is regarded as the global water cooler, the front-page of the Internet. Its “remix culture” has spawned a number of meme managers as success stories, such as Ben Lashes. The meme Grumpy Cat became the official “SpokesCat” for pet food company Friskies.

3. Creative communities

This law may be the most crucial part of the creative process, according to Allen: finding and building the right type of creative communities and partnerships. The social aspect of creativity is defined by the number, quality and duration of relationships, and appears in the choice of teachers, collaborators, muses and promoters.

Max Martin is a “hit doctor” in the pop music world, and has spawned a range of successful proteges as well. Techniques used include reusing earlier parts of the song in the chorus so that it becomes familiar, recognisable and memorable; there are also other mathematical components of composition.

D.A. Wallach is a hybrid artist-musician-investor (Spotify, SpaceX, Inevitable Ventures); he actively sought out teachers and mentors in different fields. “You can learn from anyone,” says serial entrepreneur Kevin Ryan. Such learning happens in formal and informal settings, and requires a spirit of learning, openness and even vulnerability.

Being in creative clusters based on geography is also important, such as Silicon Valley for startups. Creative density has knowledge spillovers, via availability of teachers, mentors and collaborators. Deliberate practice needs to be coupled with community feedback. Face-to-face bumping into one another can also lead to impromptu meetings.

Benj Pasek and Justin Paul (La La Land lyrics) forged their partnership from college years, and complemented their differing styles: wanderer (Pasek) and planner (Paul). Such creative friction is resolved not by meeting in the middle, but moving into a new dimension, they poetically explain.

“The Internet has made collaboration and finding your tribe a lot more convenient,” Allen explains. A “conflicting collaborator” helps discover and overcome flaws, and provides different perspectives. A “modern muse” provides support, energy, inspiration and motivation, and can even be friendly competition.

Andy Warhol’s New York studio, called the Factory, was a work-play environment for social networking among the creative community. Many artists today have lofts for such purposes.

Political stand-up comedian Hari Kondabolu draws energy from the community of comedians, and also gets material from conversations with friends. Viral video star Casey Neistat, founder of video-sharing startup Beme (acquired by CNN), surrounds himself with “countless creatively ambitious people,” who show validation, reassurance and new frontiers of what is possible.

Prominent promoters in fields like scientific research have given a valuable advocacy leg up to junior researchers by sharing credit for publications. Music stars have also done this for emerging artists, eg. Taylor Swift.

“Being in the middle, between the establishment and the fringe, helps a person create content that is familiar and credible, but also novel,” Allen explains. Legitimacy is at the centre, but novelty and freshness comes from the periphery.

4. Iterations

The fourth law is systematic experimentation and iteration. For example, Ben & Jerry’s ice cream has a repeatable system for finding the right blend of familiarity and novelty, and knowing when to retire a new product (“Flavour Graveyard”).

The process involves the funnel of conceptualisation (research and “trend treks”), reduction (surveys on uniqueness and purchase intent), curation (actual production and customer testing of samples), and feedback (public opinion, sales data). Ethical principles of social justice are also followed, such as non-GMO ingredients and fair trade.

Hollywood producer Nina Jacobson started off with “focused consumption” as a script reader, thus absorbing popular taste and the ability to “listen.” Later, as a producer, she learnt to iterate with feedback from directors and the cast, and via confidential test screenings.

A creative moderator was used to find out what select moviegoers felt about the movie. This process led, for example, to the final version of the ending for psycho-thriller Fatal Attraction. The effectiveness of movie trailers is tested by a combination of open-ended and guided questions (“aided awareness”). Interestingly, politicians also use polling extensively to test and iteratively refine campaign messages.

JK Rowlings was a rabid reader from childhood days, and her own rags-to-riches story is reflected in the narrative of Harry Potter. She spent five years in iteratively building plots of seven books, and writing the first book. She was a visionary as well as voracious planner, and persevered beyond 12 rejections before her agent found success with Bloomsbury.

The Internet has made iterative testing easier, faster and cheaper, thanks to the availability of many sources of free real-time data. “Instead of seeing creativity as a series of eureka moments and sudden epiphanies, successful creatives who use data-driven iterations are far more likely to master the creative curve,” Allen explains.

“Achieving your creative potential isn’t for the faint of heart. It requires countless hours, days and even years of work. But it’s no longer a mystery,” Allen signs off.