Expansionist, convener, or broker: How networks impact your personal and professional success

This must-read book provides valuable insights into the structure and benefits of networks, and how you can improve your network skills.

Launched in 2012, YourStory's Book Review section features over 295 titles on creativity, innovation, entrepreneurship, and digital transformation. See also our related columns The Turning Point, Techie Tuesdays, and Storybites.

A comprehensive guide to human networks and effective relationships is offered in the book Social Chemistry: Decoding the Patterns of Human Connection by sociologist Marissa King.

“How your network is shaped (consciously or unconsciously) has enormous implications for a wide variety of personal and professional outcomes,” the author begins.

Marissa King is a professor of Organisational Behaviour at the Yale School of Management. Her book is thoroughly researched, with over 58 pages of references. However, the material is presented in a highly engaging manner beyond academic audiences.

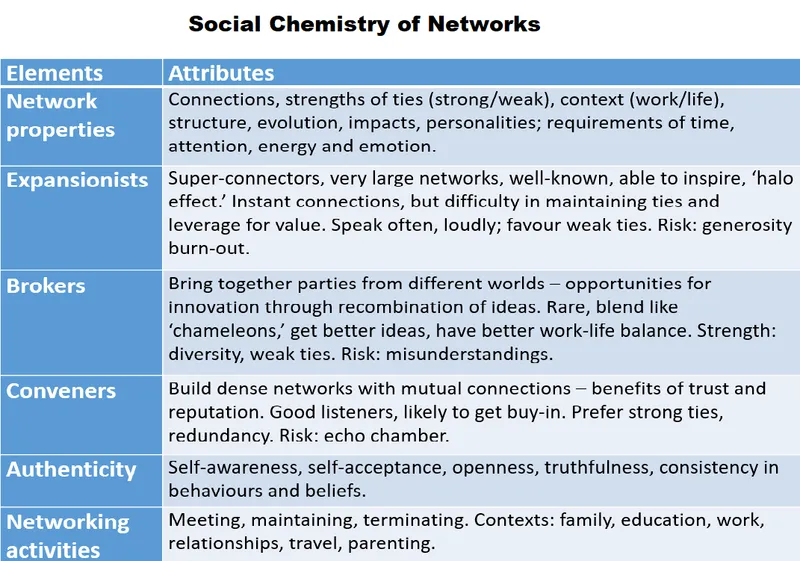

Here are my key takeaways from this valuable 358-page book, summarised as well in the table below. See also my reviews of the related books Rebel Talent, Multipliers, The Creative Curve, The Serendipity Mindset, Cross-Industry Innovation, and Innovator’s DNA.

Image credit: YourStory

The role of networks

Networks are the invisible threads of social capital that govern success in the workplace and happiness in social settings. It’s not just the size of the network, but its structure and quality that define benefits for members and network creators.

“Our networks are social signatures,” Marissa describes. She defines three kinds of networkers in this regard — expansionists, conveners, and brokers. Each has its own set of advantages and challenges in different contexts.

“The fundamental building block of relationships is reciprocity. It is the currency of social exchange,” Marissa affirms. Networks have elements of give and take. “Giving creates a warm glow or a helper’s high,” she explains.

The book also has a companion website where readers answer questions that reveal their networking style. Examples include the size of your acquaintance network, the number of members who already know each other, and whether you connect members.

Marissa draws on extensive research in this field, such as the work of Jacob Moreno (sociometry) and Robin Dunbar (Dunbar’s number). For example, 150 is the number of stable contacts we can maintain.

“Your social network can be conceptualised as a series of concentric circles that decrease in emotional intensity as you move outward,” Marissa describes. Rings include innermost circle, sympathy group, close friends, and casual friends, or stable contacts.

The size of the network is limited by the time, emotion, and cognitive capacity we can invest, thus leading to size-diversity-bandwidth trade-offs. Social networks grow through dyads, triads, cliques, and tribes. Relationships get reinforced through shared activities and common spaces.

Throughout our lives, networks can change in size and churn as well. For example, the immersive years of school and college life create a particularly strong sense of belonging. Work and parenting introduce new dynamics.

Emotional involvement

Strong ties provide mutual support. Weak ties have value in their randomness, but can be hard to mobilise, Marissa observes. Conveners prefer strong ties, but expansionists prefer a large volume of weak ties.

Some people may be natural networkers, others need to invest extra emotional energy and training. They have different expectations of immediate and long-term payoffs, the author explains.

Some networking activities are spontaneous, others are more instrumental and planned or designed. It’s one thing to be socially aware of what networking calls for, but another to be prepared and act on opportunities — this requires a flexible mindset rather than a fixed mindset.

“Self-awareness, self-acceptance, consistency in behaviours and beliefs, and being open and truthful in your relationships with others are at the heart of authenticity,” Marissa explains.

Closeness also comes with risks of high expectations, obligations, and even suffocation and betrayal, she cautions. Besides, not everyone is comfortable with showing the vulnerability that authenticity and trust demand.

Conversations

Network relationships are formed and strengthened through conversations. This calls for asking the right kinds of questions, active listening, eye contact, and physical contact in some cases.

“Open-mindedness is an asset when one is listening,” Marissa explains. Effective, deep, or compassionate listeners show that they remember key points, demonstrate behaviours like nodding, and value the meaning and emotion of the conversation without judgment.

Empathy is a key component of relationships. In cases where it may not be possible to get into the other’s shoes, it helps to be able to “walk alongside them.”

Innovation

Broker networkers play an important role in creative communities by bringing together concepts and people from worlds apart.

“Brokerage and recombination are at the core of innovation,” Marissa observes. Examples include Ferran Adria, Yo-Yo Ma, and IDEO, who draw on a diverse network of specialists.

“Brokers are the bridges between islands,” she adds. Cited research shows that academic papers written by diverse teams were more likely to produce novel insights.

“Brokers are adaptable translators,” Marissa explains. But some things may be difficult to translate and can get lost in translation.

Brokers can fit in and adapt anywhere and have a high sense of their image. They are less judgmental and more humble and are willing to be challenged and to learn.

“A good venture capitalist acts as a broker,” she adds. They connect founders with industry experts and customers. For example, Silicon Valley’s Heidi Roizen transitioned from an expansionist to a broker to a convener. In other contexts, an oscillation between brokerage and convening can be advantageous.

Networks at work

In offices, psychological safety determines the willingness of teammates to speak up about mistakes, challenges, and insecurities. Candour is more important than niceness, according to Amy Edmondson of HBS.

“Psychological safety makes companies and teams more successful because it facilitates innovation and learning,” Marissa affirms. She distinguishes between blameworthy and praiseworthy failures. Failures that yield useful lessons should be celebrated.

Conveners help set up networks with psychological safety. “There is a moment of opportunity when teams are first formed to make them psychologically safe,” Marissa advises. Small acts of civility also reinforce positivity through gratitude and acknowledgement.

She also cautions that it is important to handle toxic co-workers, rude colleagues, slackers, boors, and the “jerk at work.” Negativity is also a contagion, she warns. Power can lead to self-centeredness, insensitivity, and arrogance, as well.

“Brilliant jerks” should not be tolerated either. Some of these rules are described in Stanford University professor Robert Sutton’s book, The No Asshole Rule.

At the same time, leaders should show compassion and try to understand the causes of such toxic behaviour, such as stress or exhaustion. “Hurt people hurt people,” Marissa evocatively explains.

Office spaces can be designed to improve exposure and planned or accidental networking behaviours, as seen in the layout of desks, teams, facilities, and venues. Diversity and inclusion can improve creativity, Marissa explains.

Work-life balance

One chapter deals with the fascinating question of work-life balance. Blake Ashforth distinguishes between integrators and segmenters in this regard.

Integrators value work-life connections and even the notion of work-family, while some segmenters avoid work friendships. This has serious implications for companies where corporate social events and outings are obligatory and can impact projects and promotions.

Not everyone wants to open up about personal life at work. Work friends are a mixed blessing, Marissa cautions. They can be emotionally exhausting but also lead to more job satisfaction and cohesion. Brokers are adept in such contexts.

There are also many cases of friendships that blossomed into successful companies, as seen in Gates-Allen, Ben-Jerry, and Harley-Davidson.

Other key roles in companies are mentors and sponsors. Mentorship is enabling and empowering, while sponsors are advocates and investors.

Network evolution

Social media increases the reach and size of networks but do not have many of the advantages of physical proximity, touch, and intimacy of face-to-face settings. In fact, they invite comparison and can increase feelings of insecurity and anxiety, Marissa cautions.

Recent advances in network analytics, sociology, and computer science have improved the understanding of interaction patterns, she observes. Social media plays a role in the far edges of our networks.

Networking styles evolve over one’s lifetime, the author explains. Expansion is good in the early phases of one’s career and fields like marketing.

Broker benefits are greatest in creative industries or areas where unique work is required. Conveners are advantageous in areas where there is a lot of interpersonal uncertainty, and psychological support is needed.

Network oscillation provides fluidity and flexibility. Over time, some dormant ties may need to be reactivated or retired. “The fluidity of networks allows them to transform as our lives, emotional needs, and work demands change,” Marissa affirms.

Together, the three types of networks make the world feel small and strike a balance between order and randomness.

“Despite the differences in personality and preferences of brokers, expansionists, and conveners, they all contribute to creating a brilliant, vibrant human order,” Marissa signs off.

YourStory has also published the pocketbook ‘Proverbs and Quotes for Entrepreneurs: A World of Inspiration for Startups’ as a creative and motivational guide for innovators (downloadable as apps here: Apple, Android).

Edited by Megha Reddy