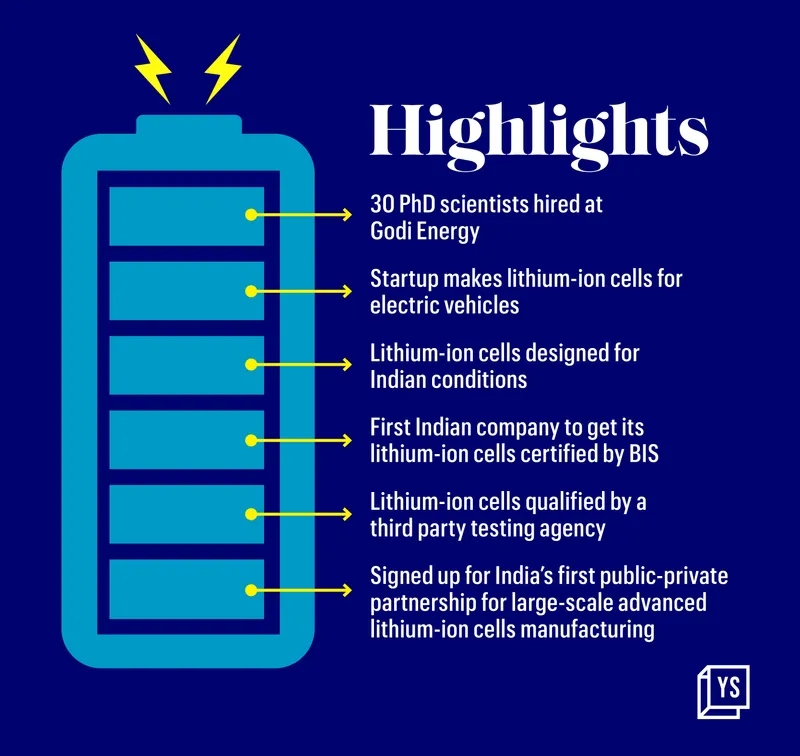

Why this startup hired 30 PhD holders to make lithium-ion cells designed for Indian conditions

Hyderabad-based Godi India, an advanced cell and supercapacitor manufacturer, has India’s largest R&D house and has brought on board 30 PhD holders to design solutions for the e-mobility and stationary storage systems sectors.

Praneetha Selvarasu took up a job as a scientist at India in May 2022 as soon as she received her PhD in nanoscience and technology from Pondicherry University. Her mother was not too convinced as she had assumed Praneetha would take up a teaching role after her research degree.

“My mom always thought I would become a professor. She had doubts about how I would survive as a woman in ‘an industrial job’. People believe that women cannot shine in industrial sectors, which isn’t true. More women should come forward to work in industrial sectors,” Praneetha says.

Praneetha is one of the 30 PhD holders who are part of Godi India’s research and development (R&D) team.

Hyderabad-based Godi India is India’s largest advanced cell and supercapacitor manufacturer that caters to the e-mobility and stationary storage systems sectors.

With a boom in EV market, this is how Neuron is eyeing a Rs 100cr turnover within 4 years

Godi India’s doctorate team

Mahesh Godi, Founder and CEO of Godi India, took a unique approach in setting up his startup to make cells and supercapacitors. He hired 30 PhD scientists to develop indigenous cells (for electric vehicles) that are suitable for Indian conditions.

Typically, a young startup does not go about hiring as many PhD folks in the very early stages—at least in India.

“Companies generally look to the rest of the world for technology, either by way of buying, investing, or joint ventures. I wanted to change the traditional way of thinking and find the right people to build technology in India,” Mahesh says.

The founder of the nearly three-year-old startup says some of the PhD holders he hired were working in Israel, Japan, Australia, South Korea, and the European and North American regions. Others went abroad for research as part of their doctoral or postdoctoral studies.

Godi India's PhD team with the startup's founder and CEO

The problem statement

The idea of doing something in the energy sector came to Mahesh when he returned to India after 17 years of working in the US. While travelling in India in 2018, he says he took stock of the road conditions and the high pollution levels and tried to understand the root causes of such challenges.

“I started studying the energy and renewables sectors and the EV industry in India. And, I began exploring opportunities in these areas,” he says.

Mahesh realised that there were enough investments and initiatives taken in the renewable energy sector as well as EV manufacturing in India, but nobody was into cell manufacturing in the country.

“Batteries account for up to 50% of the cost of an EV. I thought most related problems could be solved if somebody addressed this gap,” says Mahesh, who zeroed in on cell manufacturing in early 2019.

Finding the best talent

The next step was to find the right talent to build the technology from scratch. The lack of experienced talent in the country to set up a cell manufacturing startup was due to the lack of a native industry in India.

Mahesh reached out to his contacts in the US and Japan and educational institutes such as IITs and IIMs to get in touch with people working with cell manufacturing technology abroad.

He began by putting together a core team of PhD holders who would help with the R&D for cell manufacturing in India. The core team of 15 scientists was formed in January 2020; the others joined over a period of 18-24 months or so.

Mahesh tried to figure out each potential hire’s experience and expertise, whether they owned any patents, what kind of research papers they had published, and if they were the first author or not.

He published job advertisements on LinkedIn and claims to have received 4,000-5,000 applications.

Mahesh says it was tough to sift through the large pile of applications without an HR team in place. “Since I’m not an expert in these subjects, I took the help of some of my friends working in similar fields across the world to conduct the interviews,” he says.

On average, each candidate went through five to six rounds of (technical and HR) interviews.

Pushpendra Singh, one of the candidates selected to be a part of Godi India’s team of 30 scientists, says the ad described the job in a very detailed manner, including future possibilities.

“It has been a great learning experience for me as we keep facing various challenges from material to device to everything,” says Pushpendra, who did his PhD at IIT-Roorkee. He bagged the Fulbright-Nehru Doctoral Research Fellowship and went to Drexel University in the US to continue his PhD research.

Mahesh also tapped his network of professors at the IITs. Once he had hired a few PhD holders, they started referring friends or colleagues for relevant roles.

“I cherry-picked each and every one of the PhD holders in the team. I’ve interacted with them for hours, trying to understand what their aspirations are, why they want to come back (to India), and why they would want to join a company like this,” he says.

Mahesh was particular about getting proper representation from different parts of the country. “We have people from Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Maharashtra, Assam, Bihar, Delhi, and Rajasthan,” he says, in a bid “to capture different flavours of India”.

The hiring of PhD holders at Godi India seems to have worked well for the company and the scientists. The startup seems to be making significant progress in indigenous lithium-ion cell manufacturing even as the scientists are able to see the impact they are creating through their R&D initiatives.

“In academia, I used to wonder where all the published papers end up. They are on Google Scholar, yes. But my main question was: where were the techniques we were working on in the lab being applied?” says Praneetha, who is excited about working on “real problems” in society at Godi India.

Sasidharachari Kammari, another PhD scientist at the startup, concurs. Despite opportunities to continue in South Korea where he did his post-doctoral programme, he was clear that he wanted to come back to India.

“I wanted to work in the industrial sector and contribute to the country. I joined Godi India as it seemed like an interesting opportunity and because you end up facing more challenges to learn and grow in a startup, than in a bigger company,” he says.

Godi India's 21700 cylindrical NMC811 lithium-ion cells certified by BIS

The technology

In January this year, Godi India rolled out its first batch of commercial grade 21700 cylindrical NMC811 lithium-ion cells at its facility in Hyderabad.

Mahesh says it is the first company in India to design, develop and manufacture lithium-ion cells using indigenous technology.

The founder adds that Godi India is the first company in the country to receive the Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS) certification for its 21700 cylindrical NMC811 lithium-ion cells. To get the BIS certification, the startup’s cells were tested and qualified by TUV, a leading inspection, certification, and testing company in the country.

“There are different types of technologies within cell manufacturing, including those related to cathode, anode, binder and separator. These scientists have done very thorough academic and industrial work in these fields,” he says.

The lithium-ion cells Godi India manufactures are specifically designed for Indian conditions. Mahesh says the team took more than six months to optimise and tune the cells for Indian conditions.

For context, India does not have enough lithium reserves to make lithium-ion cells. All Indian EV makers rely mainly on Chinese cells to power their vehicles.

The core team listed a few factors to consider before designing cells for EVs in India. These include: road conditions, how vehicles are operated in India (for instance, instead of two people, three sit on a two-wheeler), and uses of the vehicles (used to transport food and other goods). The varying temperatures across the Indian terrain were also taken into consideration.

“These vehicles have a lot of vibrations when they carry goods, especially on bumpy roads and many speed breakers. We had to manufacture cells that withstand those vibrations,” Mahesh explains.

The team also wanted to make sure the cells they manufactured were eco-friendly.

“In one way, we were doing good. We didn’t want to contaminate the environment in the long term. We eliminated toxic chemicals with water and kept improving the process. We wanted to manufacture the most sustainable and recyclable cells,” the founder says.

Mahesh believes that the technology Godi India has developed can work anywhere in the world as it works in India, given its poor road conditions.

The cells manufactured by Godi India are “100% sustainable and recyclable”. The startup signed up for the Climate Pledge, co-founded by Amazon and Global Optimism in 2019, last year. Signatories (companies and organisations) of The Climate Pledge aim to reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2040.

Godi India says it has 25 patents across three main categories: materials (10), processes (10) and design (five). A few are pending approval or under review. The patented technologies cover different layers of the cells such as cathode, anode, additives, electrolyte, solvents, and separators.

The startup is working on reinventing the technology to make lithium-ion cells.

Mahesh says the team is trying to do away with industrial ovens altogether, which would help reduce the size of the factory or increase production capacity keeping the area of the facility constant.

In addition, Godi India is also working with a few equipment manufacturers to design its own apparatus to make cells.

Godi India's Hyderabad facility

Challenges along the way

Mahesh says it was an uphill climb since the company was set up in January 2020. Godi India faced supply chain challenges, especially in the beginning. For instance, it couldn’t source some of the materials required for research in India.

The startup had to establish its credibility, and the expertise and experience of the scientists helped convince sceptical companies to partner with Godi India and supply materials.

Godi India currently works with over 60 suppliers from across the world, including Germany, Japan, Korea and China, to import materials.

Just three months into existence, Godi India had to apply brakes twice due to the two major lockdowns in India. As the team had to be physically present at the facility to work on R&D, technology, and product, it was difficult to operate.

The founder says the startup had to get special permission from the authorities to work in batches at the Hyderabad facility.

Of funding and business opportunities

Mahesh claims the startup has received orders worth $200 million from EV manufacturers in India, Europe, and the US, and $50 million worth of orders for stationary storage systems.

Godi India says it has recently started shipping its cells to major Indian original equipment manufacturers.

“They will now use and validate our cells in their vehicles and also compare them with those imported from markets including China, South Korea and Japan.”

Refusing to divulge any names due to non-disclosure agreements, Mahesh says all major EV manufacturers and some of the biggest corporations in India have expressed interest in or placed orders for the startup’s cells.

Godi India’s scientists are working on reducing the price of the cells “as much as possible” as these account for up to half of the EV cost and can be another differentiating factor.

Local lithium-ion cell manufacturing is key to the EV industry’s growth in India. Recently, Ola Electric, Reliance New Energy and Rajesh Exports have signed agreements under the Central Government’s Production-Linked Incentive scheme worth Rs 18,100 crore to develop locally manufactured advanced cells.

The startup competes with Ola Electric, which is planning to begin mass production of cells from its Chennai-based gigafactory in 2023; Bengaluru-based Log9, which aims to ramp up production and set up a gigafactory by 2025; and Chennai-based Munoth Industries, which will soon begin commercial production of lithium-ion cells for the consumer electronics segment.

What does the future hold?

Godi India, which was bootstrapped in its early stages, raised an undisclosed seed fund about a year ago. It announced another undisclosed amount of funding from Blue Ashva Capital through its Blue Ashva Sampada Fund in July this year.

The Hyderabad-based startup entered into an agreement with CSIR-CECRI (Central Electrical Research Institute) in July this year to form India’s first public-private partnership for large-scale advanced lithium-ion cell manufacturing. Under the partnership, the two parties would operate and maintain advanced lithium-ion cell manufacturing in Chennai.

India's first public-private partnership For large-scale advanced lithium-ion cells manufacturing

The startup has announced an investment of $3 billion to set up multiple gigafactories in the country over the next five years. It is likely to set up its first gigafactory to manufacture lithium-ion cells by next year and will raise money in tranches to support its expansion plans.

Praneetha, Pushpendra, Sasidharachari, and their colleagues are excited about the innovations that Godi India is working on.

“I think the future is exciting. The Indian government seems to be providing a push for the EV and energy storage sectors. I think this field is going to grow big,” Pushpendra says.

Edited by Teja Lele