Waste management startups want to turn trash into cash, but garbage mafia stymie growth

In India, waste is more than a problem—it’s a billion-dollar opportunity. But behind the scenes, startups face a different challenge.

A month after the first COVID-19 lockdown, a truckful of “unruly and angry” men with wooden lathis in their hands, disembarked outside a house in Okhla, New Delhi.

Agitated, they “came barging into” the two-storey house, which was the office-cum-residence space of a startup. The angry men, led by a person who identified himself as Balu, wanted to know why the company was sending trucks to nearby nursing homes and hospitals such as Fortis and Metro Star to collect their waste.

“It’s our area. Who allowed you to collect waste from there?” the men shouted at the startup’s co-founders, who requested anonymity out of fear of reprisal.

Just two months ago, the waste recycling and management startup had received expressions of interest from hospitals and nursing homes in the area to recycle salvageable hospital waste such as gowns, syringes, and disposable clothes. Hospital waste is usually sanitised and shredded to recycle, and does not involve any human contact when done using machines.

Balu revealed that his gang had been collecting scrap from hospitals in Okhla for the past 10 years, and in conjunction with some 20 scrap dealers, made a livelihood out of hospital waste. They believed that the startup was cannibalising their business.

“They started smashing our desktop screens with their lathis and threw all of our things on the floor. We called the police, but they left before they (police) could get here,” one of the co-founders tells YourStory.

“Hospitals were against having untrained folks handling their potentially contaminated waste, but they didn’t have an option. Our pitch was clear: no human contact at all... But the gang wasn’t having it. All they cared about was getting us out of their way,” the co-founders say.

When the co-founders approached the local civic bodies, they were told no one wanted to deal with the “garbage gangs”. Even the police refused to register an FIR, saying, off the record, that Balu was the henchman of a local politician.

This incident, however, wasn’t an anomaly; eight of the 13 companies YourStory spoke to recounted running into similar problems. The other five reported hearing similar stories from their peers in the space.

Waste management in India is a huge business. Mordor Intelligence pegs its market size at $12.90 billion in 2023, and says that, by 2029, it could be worth $17.30 billion.

India currently generates around 62 million tonnes of waste overall, out of which only 20% is recycled—the rest ends up in landfills and oceans, affecting human and marine life, as well as destroying the environment, according to the Ministry of Environment, Forest, and Climate Change.

Only 30% of the recyclable waste is currently recycled, according to the Mordor Intelligence report, and a majority of it is done by unorganised factions that almost operate as monopolies with little tolerance for intrusion from others.

In fact, in a lot of neighbourhoods that spring up around landfills, across the country, one can find a plethora of small-scale businesses, each striving to eke out a living by selling stacks of recyclable waste to wholesale dealers.

A thriving business

According to Salim Mohammed Khan, a scrap dealer who had been illegally running his business until 2022, there are at least a dozen such illegal scrap trading businesses that operate near Deonar, a landfill on the outskirts of Mumbai.

“Deonar does business of Rs 300-500 crore every year at least. People have become crorepatis from this kachra (garbage),” quips Khan, who legitimised the business after his brother was arrested a couple of times for operating illegally.

Last year, Khan’s business made Rs 1.6 crore in revenue, out of which it earned a profit of Rs 97 lakh—much more than some of the country’s valuable startups.

These small, mostly illegal enterprises, operate the old-fashioned way—they enlist waste pickers from economically disadvantaged or backward communities, and employ them as manual scavengers.

The waste pickers usually enter landfills without permits from the local municipal bodies. They also work under inhumane conditions, without any manner of protection, even when dealing with hazardous materials.

But for many, this is their bread and butter--they’re paid for the garbage they collect by scrap dealers, who then go on to sell all of this recyclable waste to bigger recycling businesses.

For startups, this system doesn’t work.

Firstly, it relies heavily on outdated practices such as employing manual scavengers in hazardous conditions without proper protection or legal permits, which not only raises ethical concerns but also poses potential legal and reputational risks.

Secondly, buying scrap to recycle limits scalability, which makes it a capex-heavy endeavour, especially since the margins in the business are quite thin.

And finally, paying a premium to purchase scrap from dealers makes no financial sense, especially when startups can directly source it from waste-generating entities such as hospitals, apartment complexes, tech parks, etc., for a fraction of the cost.

Despite being a major contributor to India’s pollution woes, the waste management sector raised merely $12 million last year across four deals, as per YourStory data. The climate-tech sector, overall, raised $1.2 billion.

The challenges

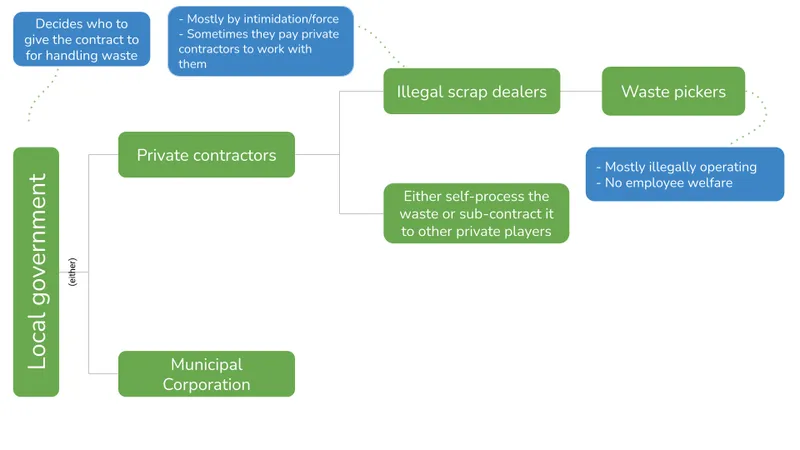

There’s a permutation-combination of agencies involved in recycling India’s waste.

At the very top, there is the local government, which decides how garbage in their jurisdiction will be dealt with. The government either entrusts municipalities with the task, or contracts it out to private players.

The private players are usually either big, legitimate companies such as Let’s Recycle and Vermigold Ecotech, or unregistered, illegally operating individuals who have the muscle power to intimidate and bully the private competition and are “willing to share the wealth” with administrators.

The private contractors are tasked with sorting out the waste, end-to-end. They’re supposed to collect the waste, segregate it, and then sell it to other recycling companies.

The reality of what goes down after waste is collected is a lot different though.

In a lot of cases, the private contractors are either “coerced or financially incentivised” (in the form of monetary kickbacks) by government authorities or the local mafia to work with the unorganised sector—mostly the scrap dealer and his gang of waste pickers—in exchange for a set fee, says the founder of a Maharashtra-based e-waste recycling startup, who also requested anonymity due to fear of backlash.

At the bottom of the hierarchy are scrap dealers who employ waste pickers. There’s usually an understanding between the scrap dealers and the private contractors to protect each other’s interests so they can monopolise business in the area.

Amidst all this, startups say they face resistance at two levels—first, from municipalities that have a vested interest in protecting local businesses.

Municipal corporations usually don’t bother companies like us if we take the onus of collecting waste directly from the source, i.e., residential complexes and company offices, for example.

The issue starts when you try getting access to waste collected by them, says Abhishek Agarwal, Founder and CEO of Goodeebag, a Hyderabad-based waste management company that enables people to schedule pickups for their segregated waste in exchange for points that can be redeemed at their online gift shop.

The second resistance is from the scrap dealer mafias who often use intimidation tactics to drive out any potential competition, especially if it’s an organised entity.

“The legitimacy (of lawfully registered and operating startups) scares them. They worry about losing business, but their bigger concern is losing workers because some companies poach them by offering better wages, sanitary conditions, access to protective gear, etc.,” says the founder of an early-stage Mumbai-based waste management startup who spoke on the condition of anonymity.

The way around

Despite the challenges, some startups have managed to figure out ways around these issues.

“We work closely with waste pickers in landfills. We provide them with training, safety kits, salaries, etc., and whatever they segregate, they sell it to us at the end of the day and we pay them as per the market rate,” says Anurag Asati, Founder of , a Bhopal-based waste management startup.

The idea is that rather than facing opposition from two adversarial parties—the scrap traders and the waste pickers—startups can have one ally among them.

Employing these waste pickers is not an easy endeavor though.

Startups such as The Kabadiwala, which work in conjunction with waste pickers, have had to deal with bullying, intimidation, and threats from scrap traders, and sometimes the only recourse is a collective protest by the waste picker community.

“We’ve had this community fight goons for us just because we give them better working conditions…really goes to show the apathy these workers have to face day in and day out from mafias that don’t want to do more than the bare minimum for these communities but also want to maintain a stranglehold on them,” one of the founders quoted above says.

Another workaround is collecting garbage from the source itself—hospitals, residential complexes, office buildings, manufacturing facilities, etc. Some consumer-facing platforms even go so far as to leaving the choice with the users; if you have scrap or potentially recyclable materials, you can book a pickup.

For instance, Goodeebag enables users to schedule pickups at their convenience, regardless of whether the company has a direct partnership with the apartment complex’s welfare association.

“But it becomes hard to predict when you’ll have the opportunity for a next pick up for sure,” the founder of Goodeebag says.

A handful of startups YourStory spoke to did report receiving support from local civic bodies and administrative officers, especially if they could demonstrate strong tech-led solutions.

They also said there was little to no resistance for electronic and battery waste since most scrap dealers did not want to bother with investing in technologies to recycle them, and also because its collection and processing are heavily regulated, controlled and supervised.

In the case of EV batteries, for example, automakers in India are obligated to ensure that the batteries they introduce in the market are effectively recycled, refurbished, or repurposed at the end of their lifecycle. Called extended producer responsibility (EPR), the regulation aims to prevent hazardous waste from accumulating and causing adverse environmental impacts.

Show me the money

The ultimate question is whether the obstacles posed by these entrenched interests pose sufficient risk to deter investors from supporting waste management startups, particularly those aiming to address municipal and household waste challenges.

The answer is yes and no.

While scaling and uncertainty remain an issue under the current mode of operation, VCs assert that viable solutions exist, and that startups capable of resolving execution challenges will ultimately spearhead changes in the sector.

“Every organised sector in India was once unorganised, and whenever there is a new player in town, there will be resistance. It’s a natural part of the process,” says Anjali Bansal, founding partner of , recalling a time—about 15 years ago—when the logistics sector, facing comparable challenges, became consolidated and organised.

“Ultimately, it is a question of being able to figure out your execution. Are waste management startups investable–YES! The founders and their teams will have to build strong operating capability, and that is something investors will look for in this space…the ability to build strong operating processes, and then use technology to digitise and create efficiencies,” she adds.

Omnivore Capital’s Investment Director Abhilash Sethi, drawing parallels between the agricultural and food waste sphere with the municipal waste sector, points out that certain facets of the latter, notably plastics, are progressively becoming organised.

Similar to agricultural waste, the final product resulting from recycling other types of waste should also command a significant premium. This, he explains, would provide companies in the sector more firepower to offer higher rates for raw materials, ultimately leading to a decrease in competition as suppliers gravitate towards those offering better compensation.

“The moment you have a healthy gross margin to play with, all these inefficiencies of aggregating fragmented supply and paying something extra to the suppliers or lower-level aggregators such as waste pickers can be taken care of. You can actually offer a better buying price and you will attract people to sell to you.”

Finally, though, Sethi says it’s all about intent—even though the unorganised sector often faces flak, it historically has and continues to play an instrumental role in cleaning up India’s cities, he quips.

“It’s easy to paint the unorganised sector as a negative entity, but the reality is that they have been helping us. Instead of feeling threatened by them and vice versa, the way forward is to pull these unorganised businesses into organised channels and creating a win-win situation.”

Finally, despite all the operational challenges in a sector that’s riddled with bad players that make it tough for startups to make a meaningful impact, things are changing quite slowly, but they’re also slowly changing.

(Cover image by Nihar Apte)

(Story has been republished to update infographic)

Edited by Megha Reddy