Women’s jobs 1.8 times more vulnerable than men’s during the pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has taken a toll on women all over the world. While women have always been juggling responsibilities with multi-tasking being a norm, the pandemic has only added to their woes.

Working women are bearing the brunt in different ways. Working from home often means extended working hours, added caregiving responsibilities, and also micromanaging online schooling if there are children involved.

All these factors have caused a shift in the way women look at their careers in the “new normal”- which seems to be here to stay.

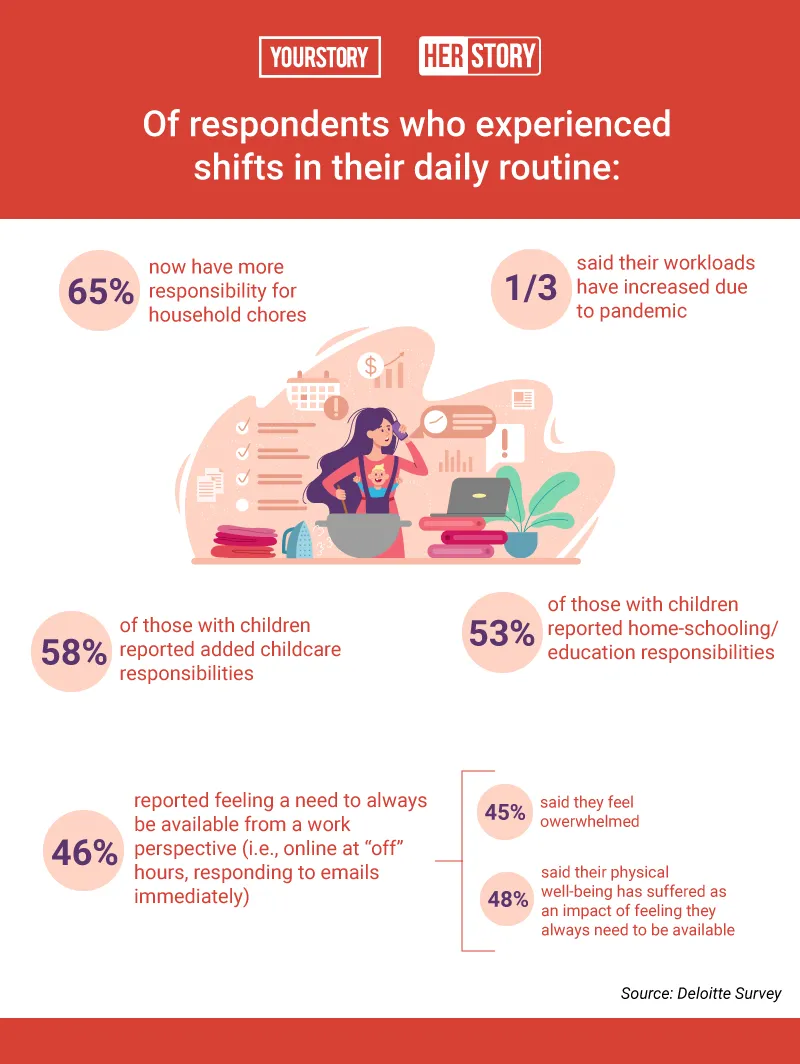

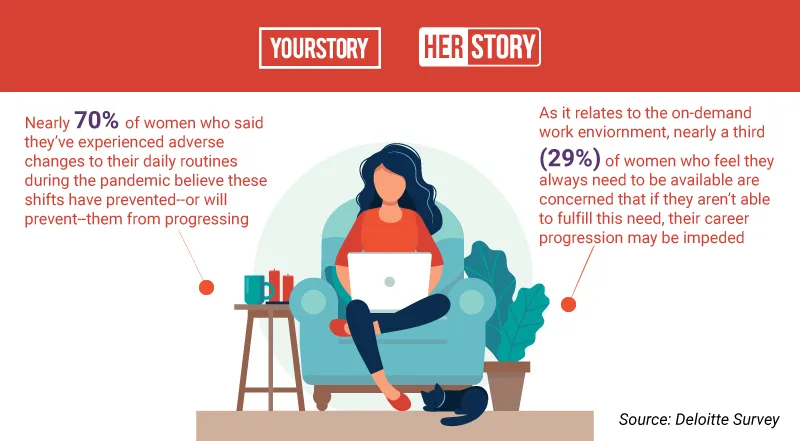

A global survey by Deloitte finds that nearly seven out of 10 women who experienced negative shifts in their routine as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic believe their career progression will slow down.

Nearly 82 percent of women surveyed said their lives have been negatively disrupted by the pandemic, and nearly 70 percent of women who have experienced these disruptions are concerned their career growth may be limited as a result. Add to this, the rise of an on-demand work culture is also making women feel that if they are not online all the time, they may lose out on career growth.

Sadly, this has only led to more women leaving the workforce, pushing back the diversity agenda in organisations. How have companies dealt with the numerous concerns working women have? What can organisations do to make it easier for women to be part of the new working normal? What are the right HR policies and frameworks that put women first during this pandemic?

HerStory, in a series of interactions with HR heads, Founders and CEOs of organisations, and with the help of data from various reports and our own dipstick survey, examines the impact and also attempts to provide solutions so that there is no further drop in gender parity.

Data: Deloitte Survey

Introduction

The world was taking baby steps towards gender diverse workplaces and cultures when the COVID-19 pandemic struck, and pushed us back a few years. There are many reports that prove that women have been affected more during this pandemic when compared to their male counterparts.

A McKinsey Report pointed out that women’s jobs have been 1.8 times more vulnerable during the pandemic than men’s jobs. Women make up 39 percent of global employment, and yet, in May 2020, they accounted for a whopping 54 percent of overall job losses.

This not only is a massive blow to the progress of women but also the economy at large. An HBR Report says, if there is no action taken to counter this effect, the global GDP growth will be $1 trillion lower in 2030. On the other hand, if action is taken, then it can add $13 trillion to the global economy in the same year.

“A middle path - taking action only after the crisis has subsided - would boost the economy but reduce the potential opportunity by more than $5 trillion,” according to the report.

Rashmi Urdhwarshe, Indian Automotive Engineer and Director of Automotive Research Association of India believes the impact of the pandemic has been different for women in different sectors.

While the manufacturing sector saw a slump during the early days, women began returning to the shop floor once the lockdowns lifted, but the numbers aren’t enough.

“Their numbers are significantly dropping as there isn't much work, also there are fewer jobs, so women, by default, are dropping off,” adds Rashmi.

Multi-tasking of a different kind

In the Deloitte report that surveyed 400 working women across nine countries including India, 89 percent said demands on their personal time and daily routine have changed due to the pandemic, with 92 percent of that group indicating that these shifts have had a negative impact.

Additionally, the number of women who say they are responsible for 75 percent or more of caregiving responsibilities (e.g. childcare or care of other family members) has nearly tripled to 48 percent during the pandemic, compared to their caring responsibilities prior to COVID-19.

Ajay Kumar, Head - Human Relations, Continental India, says, “According to a report by the World Economic Forum, it will take another 99.5 years to achieve global gender equality. Pay scale findings state that the women’s labour force participation is at a 33-year low as more women are taking on caretaker roles owing to the pandemic and everything going virtual. Additionally, emerging economies still have a long way to go in bridging the gender equality gap.”

There are multiple reasons for this drop - managing work from home versus work at home, lack of a strong support system, managers that lack empathy, and all of the above.

HerStory conducted a dipstick survey on Twitter to understand the main causes for women leaving their jobs during the pandemic.

54.5 percent voted for ‘all of the above’, while 20.1 percent attributed this to ‘managers that lack empathy’, 14.2 percent said there was little or no support, and 11.2 percent said it was juggling work at home and working from home.

Ankiti Bose, Co-founder and CEO, Zilingo says, “We are currently witnessing women around the world being deeply affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, as it continues to heighten the large and small inequalities, both at work and at home, that women face regularly. The prolonged uncertainty of the pandemic has increased the burden of unpaid care - cooking, cleaning, shopping, taking care of children and parents in the household - responsibilities that are disproportionately carried by women.”

She explains that caregiving at home coupled with additional stress at work has had women reporting pressure to always ‘be on’.

Rashmi Urdhawarshe, explains that companies are also taking longer to adjust and adapt to new working norms and requirements. This in turn is making it harder for women to find the much-needed balance.

Data: Deloitte Survey

The role of the primary caregiver

“Women are still primary caregivers in any household. And hence, are forced to juggle multiple roles. With fulltime responsibilities of schooling and engaging children, it has definitely put additional pressure on us,” adds Minu Margaret, Founder and CEO, BlissClub.

Ankiti adds that with only 22 percent of women globally believing their employers have enabled them to establish clear boundaries between work and personal hours, women have been forced to rethink their priorities and career trajectories.

“Juggling roles, with both familial and professional pressure to perform to the best of their capabilities, is what is making women reassess career paths. If these trends are left unaddressed, they will aggravate existing inequalities and reverse decades of progress towards an inclusive economy for women,” she says.

Backing this up, the McKinsey study reveals that women’s employment is dropping faster than average, even accounting for the fact that women and men work in different sectors. The nature of work remains significantly gender specific, with women and men tending to cluster in different occupations.

This shapes the gender implications of the pandemic: The analysis shows that globally, female jobs are 19 percent more at risk than male ones simply because women are disproportionately represented in sectors negatively affected by the COVID-19 crisis, such as accommodation and food service.

“Now, with Covid-19, women have borne the brunt of the economic impact. Women’s employment is dropping faster than average, even accounting for the fact that women and men work in different sectors. The nature of work remains significantly gender specific, with women and men tending to cluster

in different occupations. This shapes the gender implications of the pandemic: Our analysis shows that globally, female jobs are 19 percent more at risk than male ones simply because women are disproportionately represented in sectors negatively affected by the Covid-19 crisis, such as accommodation and food service,” says the report.

The numbers are not looking good

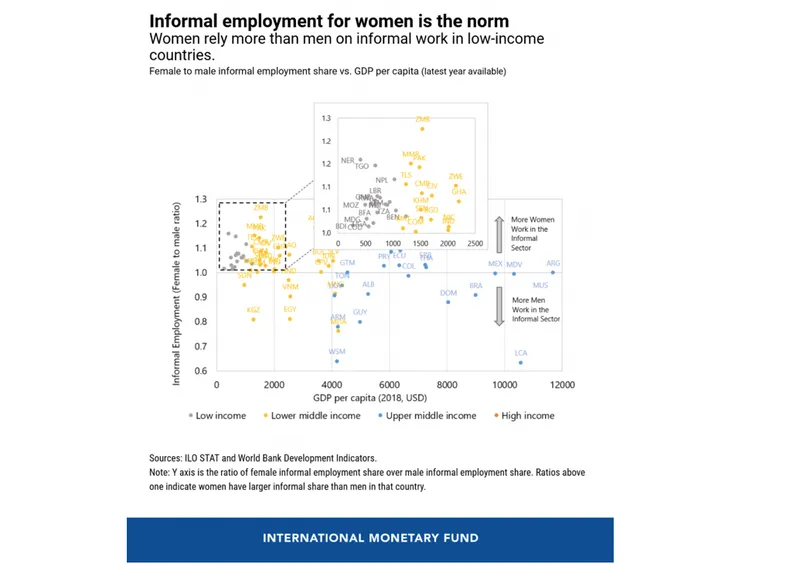

It has been noted in the IMF report that gendered nature of work across different industries still accounts for only one-fourth of the difference between job-loss rates for men and women.

For example, in the US, before COVID-19, women made up close to 46 percent of the workforce. Now factoring the industry-mix, women are estimated to make up 43 percent of the job losses. But the unemployment data shows a higher number, suggesting that women make up over 54 percent of the overall job losses.

On the other hand, in India, women made up 20 percent of the workforce prior to the pandemic. The report said their share of job losses resulting from the industry mix alone is estimated at 17 percent - they actually account for 23 percent of overall job losses.

Source - IMF

An International Monetary Fund (IMF) report adds that women tend to do more unpaid work than men, approximately 2.7 hours more per day.

It added that women bear the brunt of family care responsibilities that have resulted from the pandemic-induced shutdowns - school closures and precautions for elderly parents.

After shutdown measures are lifted, women are slower to return to full employment. In Canada, the May job report shows that women’s employment increased by 1.1 percent compared with 2.4 percent for men, as childcare issues still persist. Furthermore, among parents with at least one child under the age of six, men were roughly three times more likely to have returned to work than women.

“An important one is the burden of unpaid care, the demands of which have grown substantially during the pandemic. Women do an average of 75 percent of the world’s total unpaid-care work, including child care, caring for the elderly, cooking, and cleaning. As COVID-19 has disproportionately increased the time women spend on family responsibilities, women have dropped out of the workforce at a higher rate than explained by labour-market dynamics alone,” said the report.

Data: Deloitte

The economic conundrum

According to a report by the IMF, the pandemic threatens to roll back gains in women’s economic opportunities, widening gender gaps that persist despite 30 years of progress.

The same report also stated women have also had to bear the fallout of some key industries. As sectors such as tourism, social, hospitality and retail, where women are generally employed in higher numbers, require face-to-face interactions, and which in turn have been hit by the pandemic due to social distancing measures, women employees have indirectly been on the receiving end.

“Because of the nature of their jobs, teleworking is not an option for many women. In the United States, about 54 percent of women working in social sectors cannot telework. In Brazil, it is 67 percent. In low-income countries, only about 12 percent of the population is able to work remotely,” stated the report.

Another important factor is that women are more likely than men to be employed in the informal sector, especially in low-income countries. This means they are often compensated with cash and no structured processes. Thus, labour laws can offer only limited protection and other benefits like health insurance or pension are simply ruled out.

“The UN has pointed out that the pandemic will increase the number of people living in poverty in Latin America and the Caribbean by 15.9 million, bringing the total number of people living in poverty to 214 million, many of them women and girls.”

The report also stated that the number of women at risk of losing human capital is higher. It said that in several countries, the number of young girls who are forced to drop out of school and work to supplement household income is rapidly increasing.

A Malala Fund report said the share of girls not attending school nearly tripled in Liberia after the Ebola crisis. In schools in Guinea, 25 percent less girls re-enroll than boys.

For India, the report added that - since the COVID-19 lockdown went into effect, leading matrimony websites have reported 30 percent surges in new registrations as families arranged marriages to secure their daughters’ futures. Without education, these girls suffer a permanent loss of human capital, sacrificing productivity, growth, and perpetuating the cycle of poverty among women.

The impact on women entrepreneurship

Apart from women in the workforce, the impact of the pandemic is also seen on female entrepreneurs - this includes women-owned SMEs and MSMEs in emerging economies, according to a HBR report.

The report stated these enterprises account for a high share of female labour-force participation. The crisis may have made some family resources scarce, including investment capital or digital devices that families must now share as children’s schooling has gone online.

“Attitudes also shape how women experience the economic consequences of a crisis relative to men: Traditional mindsets may be reflected in current decisions, at the organisational level or even within the family, about who gets to keep their jobs. For example, according to the global World Values Survey, more than half the respondents in many countries in South Asia and MENA agreed that men have more right to a job than women when jobs are scarce. About one in six respondents in developed countries said the same,” said the report.

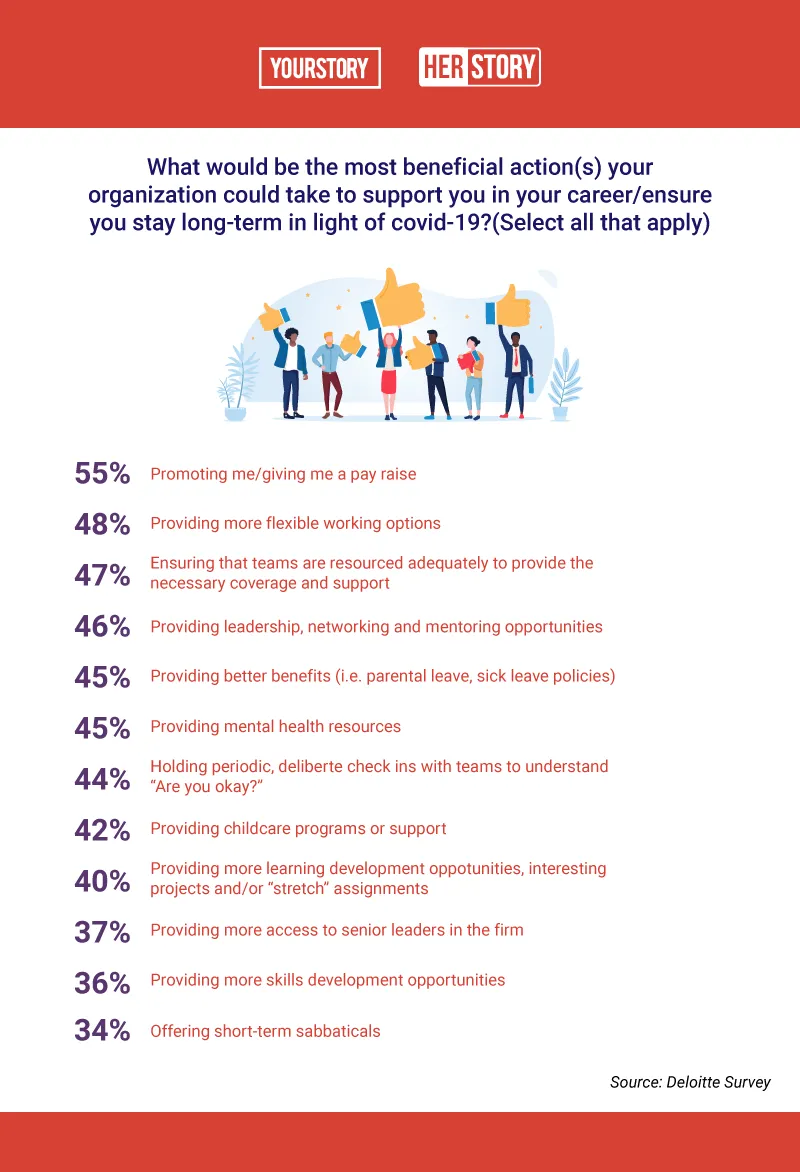

The Deloitte survey found that nearly half of respondents cited the availability of leadership, mentoring, networking, and sponsorship opportunities as beneficial to their careers. These resources can be meaningful platforms for career growth. However, it is important to ensure that such opportunities are offered in a variety of ways and times to ensure more women in your workforce can leverage them.

For example, hosting early morning networking breakfasts that clash with responsibilities at home will likely result in some women feeling excluded.

“Women have a larger domestic commitment in some societies. While most of our development initiatives are gender agnostic, Continental thus has some very specific initiatives for mid to senior women colleagues such as WE-LEAD (Women Leadership Engagement and Development Program) through which our women colleagues go through rigorous learning and mentoring interventions,” adds Ajay.

This helps in meeting their professional aspirations and opens a multitude of opportunities to support long and successful career trajectories. Role modeling by the managers to maintain a good work-life balance has also been a big win. Inclusivity sensitisation also helps in ensuring robust practices around diversity and related concerns.

One step forward, two steps back

The IMF report added that there will be a need for policies that foster recovery. Policies that can possibly mitigate any negative effects of the crisis on women and further setbacks in gender equality.

Ankiti opines that the slow return of women to the workforce may further widen the underrepresentation of women in managerial and leadership positions.

As most developed and developing countries work towards bringing back flourishing economies, women’s needs must be addressed and taken care of for a greater global GDP, and to tackle the underrepresentation of women in positions of leadership and power.

“In India, we lack a good infrastructure to support women in their careers. This factor has been evident in the pandemic, where children are attending classes virtually and require a parent to be at home,” explains Sudhakar Balakrishnan, Group CEO, FirstMeridian Business Services.

The negative impact comes at a time when gender parity was making a slow forward progress. A McKinsey Global Institute (MGI) Power of Parity work from 2015 onwards had analysed 15 indicators of gender equality across four categories. These are:

- Equality in work

- Essential services and enablers of economic opportunity

- Legal Protection and political voice

- Physical security and autonomy

Quoting these parameters, an HBR report said - using these indicators, MGI established a strong link between gender equality in society and gender equality in work — and has shown that the latter is not achievable without the former.

The report added that despite a growing awareness of and support for greater gender equality, tangible progress toward equality in work and society stagnated in the five years between 2014 and 2019.

It stated that the level of women participating in the labour force hasn't moved much from 2014 to 2019. It has been at two-thirds that of men in the workforce.

Change must be quick

As stated earlier, this can have a significant negative impact on the global economy. Ankiti explains, on a global level, the loss of women from the workforce has major negative implications including severely impacting the growth of the economy. Global GDP growth could be $1 trillion lower by 2030 than it would be if women’s unemployment simply tracked that of men.

“The idea is to create more inclusivity, especially during unprecedented situations such as these. We cannot determine the ways of working to be the same for all employees, especially women. The approach forward must be to better understand, equip and support all segments of working women effectively to ensure their contribution to the workforce remains constant, if not more.”

An HBR report explains that reversing the regressive trend will need - investment in education, maternal mortality prevention, unpaid care work, family planning, and digital inclusion.

The report adds that incremental public, private, or household annual spending in the above areas needs to rise to 20 percent to 30 percent in 2025, much above the business as usual levels or a total of $1.5 trillion to $2. trillion.

The report further said - by comparison, the economic benefits of narrowing gender gaps are six to eight times higher than the social spending required. The investment is just a start.

Policy efforts

It is a given that policymakers need to adopt measures that reduce the effect of the pandemic on women. The report advises a focus on extending income support to the vulnerable, providing incentives to balance work and family care responsibilities, access to family planning and better healthcare.

There also is a need to expand this support to the self-employed and small business owners as well. IMF stated there are legal barriers that can be removed against women’s economic empowerment. Citing examples of countries that have already adopted some of the policies, the report stated:

- Latin American women leaders have established ‘Coalition of Action for the Economic Empowerment of Women’ as part of a wider whole-of-government effort to increase the participation of women in post-pandemic economic recovery.

- Italy, Portugal, Austria, and Slovenia have introduced statutory right to partial paid leave for parents with children of a certain age bracket.

- France has expanded sick leave to parents impacted by the closure of schools. Especially for those who have no work arrangements for childcare or alternative care options

- West African country Togo has a new mobile cash transfer programme with a 65 percent participation of women. The programme helps informal workers to receive grants of 30 percent of the minimum wage.

The report has stated that policies can be designed to tackle gender inequality by creating incentives and conditions. There needs to be fiscal policies of investing in subsidising childcare, parental leave, education and infrastructure.

Inclusive all the way

“Organisations need to be women-friendly, more importantly during times of crises. The flexibility of working hours is one of the essential requirements of any employee, regardless of gender. It allows both men and women to share responsibilities of a household, making inroads against stereotyped roles,” says Sudhakar.

Gender equality is an important subject that needs addressing. Organisations must guarantee that this is not harmed, especially in times of crisis.

“The pandemic has resulted in a hybrid work model, which has benefitted many working women, particularly in the IT and related sectors. Many women can enter the workforce again or continue their employment, primarily due to the hybrid work model,” he added.

Paid time off and healthcare benefits are also other necessary measures that an organisation should provide. Many companies had started sensitisation programmes much before the pandemic hit. These initiatives aim to remove unconscious biases, help in reskilling and training, and provide equal opportunities to women.

“Having women in the workforce isn’t a choice or some sort of affirmative action for organisations. Women form a significant part of the talent pool and it is to the company’s advantage to ensure good representation of all demographics. At Continental, we realise this aspect, and also consider it our responsibility to ensure gender parity at the workplace. Hence, we do not see it as an option per se,” says Ajay.

Conclusion

Thus, to ensure that this drop of women from the workforce does not further impact the global economy adversely, there is a need for changes at the organisational level, in policy, and individual shifts.

Minu says:

“I honestly believe our society (globally) is in a stage of evolution, which I believe is for the better. We have a long long road ahead of us, but we are inching towards it. Not having half the population, able to contribute toward progress and scientific evolution, because we are entrusted with the singular responsibility of childcare and household responsibilities is just inefficient for humanity. We need to have more women solving problems, which probably only we know exists.”

Edited by Rekha Balakrishnan and Anju Narayanan

![[100 Emerging Women Leaders] Meet Rianjali, who braved vocal cord polyps to work with musical maestro AR Rahman](https://images.yourstory.com/cs/4/a9efa9c02dd911e9adc52d913c55075e/RIANJALI-2-1626433165970.jpg?fm=png&auto=format&h=100&w=100&crop=entropy&fit=crop)

![[100 Emerging Women Leaders] Why this 18-year old built Varnan, a virtual storytelling platform comprising grandma's tales](https://images.yourstory.com/cs/4/a9efa9c02dd911e9adc52d913c55075e/Imagel7l0-1625142943411.jpg?fm=png&auto=format&h=100&w=100&crop=entropy&fit=crop)