A Padma Shri awardee, this nurse is working towards tribal healthcare in the Andamans

Shanti Teresa Lakra is a social/community nurse serving the Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups (PVTGs) in the Andaman Nicobar Islands. From 2001-2006, especially during the tsunami, she helped the Onge, an endangered tribal group in the region, with timely medical help and attention.

Key Takeaways

- Shanti Teresa Lakra is a social/community nurse serving the PVTGs in the Andaman Nicobar Islands.

- She started working with the Onges in 2001

- Lakra is a Padma Shri awardee

- She has been selected as one of the top finalists for Aster Guardians Global Nursing Award 2023

In 2004, when the tsunami hit the Andaman coast, Shanti Teresa Lakra had already spent three years as a nurse at the sub-centre in Dugong Creek, a remote area of Little Andaman. The area is home to the Onge, one of the oldest tribes in India, said to be part of Negrito racial stock.

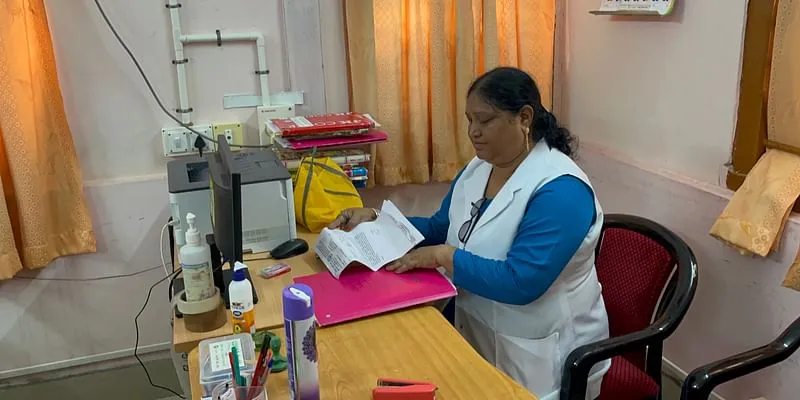

Shanti Teresa Lakra

Less than 100 in number at the time, Lakra dedicated herself to the healthcare of the Onge, who were initially wary of any form of outside support. With no access to medical histories and barriers of language, the auxiliary nurse, with constant visits, befriended them and convinced them to avail of the medical facilities at the centre.

Almost two decades later, the Florence Nightingale Award and Padma Shri winner recounts the terrible destruction and challenges she faced in the aftermath of the tsunami.

“The tsunami washed out the entire settlement at Dugong Creek and we had to retreat further into the forest and live in a makeshift tent. There was no communication with the outside world, or medical supplies for a long time,” she recalls.

With the tsunami bringing with a range of diseases and trauma, Lakra had to scour for medicines, sending messengers to walk 12-15 km to get emergency medicines for the Onge.

During all the destruction, a pregnant Ongee woman delivered a baby just weighing 900 grams.

“I had to save both, keep them warm, and practice kangaroo mother care. We managed with very little firewood and once communication lines were in place, I requested a chartered flight from the nearest referral hospital, GB Pant Hospital, in Port Blair. I had very little hope for their survival, but after six months, the mother and baby came back healthy,” she says. She helped 3-4 deliveries in one night, all on her own.

Her personal life too was not without incident. She was staying with her one-year-old son and her husband, who was running his own business on another island. Severely malnourished because of lack of proper nutrition, her in-laws stepped in and took her baby to live with them.

“Doing my duty”

Lakra becomes emotional as she talks about her experiences during the tsunami, but nothing, she says, would have stopped her from doing her duty.

She stayed on for two more years with the Onges, not being able to visit her family during the period.

“As the Onges shifted further to the forests, I had to often walk for hours, wading through a sea on high tide, and trekking through dense vegetation to provide them with healthcare and rehabilitation. There was no way I would have left them on their own, without support,” she adds.

At the end of 2006, Lakra was transferred to GB Pant Hospital in Port Blair. She serves in the Special Ward, especially meant for Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups (PVTGs) referred from different primary health centres (PHCs) of tribal and remote areas.

“Along with other staff of Andaman Adim Janjati Vikas Samiti (AAJVS), we work in the tribal word for watch and ward duty, 24X7. I attend to patients, their personal hygiene, arrange food and clothing, make beds, and also accompany patients to the referred doctors, and for various investigations like X-ray, ECG, USG, CT scan, and MRI,” she says.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, Lakra and the team travelled to various tribal settlements, often for 5-6 hours in a dinghy, traversing high waves, not knowing whether they’d return to their camp.

“With our efforts, they had managed to isolate themselves well, and were taking good care. However, our goal was to get them vaccinated quickly so that the disease would not spread further,” Lakra says.

A far cry from the initial days when she had to navigate cultural, social, and language barriers to reach out to them.

“Respect is important. We understood that it was important to respect their culture, their beliefs, and lifestyle. I am happy to say that most tribes now are not averse to seeking medical help and attention. Women regularly attend ante-natal checkups. There’s also a difference in the weight of babies born–from less than 2 kg to around 2.5 to 2.75 kg, all very good signs,” she adds.

Lakra continues to win accolades for her work. Recently, she’s been recognised as one of the top 10 finalists for Aster Guardians Global Nursing Award 2023, where one nurse will win the grand title award of $250,000 at an event in London on May 12, celebrated as International Nurses Day.

The 52-year-old is thankful for the recognition, but believes the sense of satisfaction she gets from her work, and helping people in need drive her. Inspired by her older sister, who is also a nurse, and her parents’ love for seva, she thinks of it as a divine calling. She’s also all praise for her husband and in-laws who continue to support her in every endeavour.

“Just recently, a young girl came to me and touched my feet. She told me that she was one of the babies I had delivered during the tsunami. I was touched,” she says.

Her eyes well. “I want to continue doing this work as long as I live.”

Edited by Megha Reddy