Meet the IAS officer at the forefront of climate action, sustainability in Tamil Nadu

In our Women in Governance series, we feature Supriya Sahu, Additional Chief Secretary, Department of Environment, Climate Change and Forests, Government of Tamil Nadu. She traces her 32-year career and speaks about the man-animal conflict, wildlife conservation, and the Meendum Manjapai campaign.

More than 20 years ago, when IAS officer Supriya Sahu was posted as district collector in the Nilgiris, she launched the People’s Campaign Against Throwaway Plastic, an initiative much ahead of its time.

“Twenty-three years ago, no one was even talking, let alone banning single-use plastic. I started this campaign with a group of volunteers and officers to raise awareness and put this into effect. I am glad that many years later, the Nilgiris still practises this,” she tells HerStory.

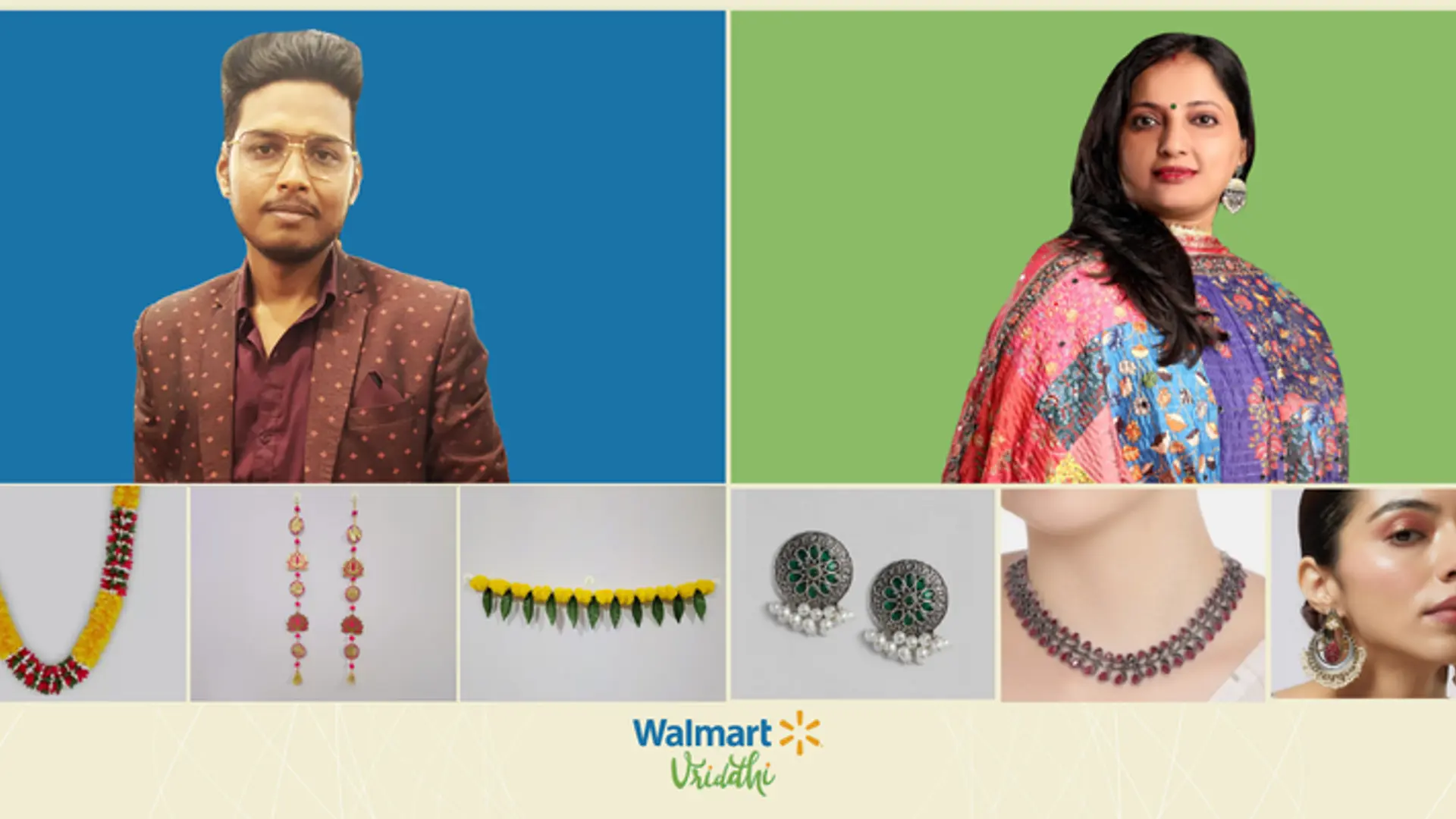

Supriya Sahu, IAS

The 1999-2002 stint in the Nilgiris, was memorable in more ways than one. Sahu recounts the period with a lot of pride.

“The district gave me the opportunity to see nature in its most pristine form. It is a biodiversity spot, and a place with indigenous people and several tribal groups. The people are simple and humble and despite the differences in culture and language, it was an immersive experience,” she says.

During this time, with the collective effort of the district administration and the people of Nilgiris, a Guinness record was achieved for planting 42,182 trees in Kurthukuli village. These experiences, Sahu believes attracted her to nature, wildlife, and to communities, and above all, the power of teamwork.

Sahu also led the initiative for the first door-to-door survey of people living with disabilities in the district, a first in India.

“We made a list, organised a door-to-door survey and gave people with disabilities certificates at their doorstep, so that they could avail of benefits. Both the anti-plastic campaign and this project were documented by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP),” she explains.

Sahu joined the Indian Administrative Service in 1991, as part of the Tamil Nadu cadre. Since then, she has been posted in Tirunelveli, Vellore, the Tamil Nadu Aids Control Society, and was also appointed as Joint Secretary at the Information and Broadcasting Ministry, among others.

New pathways for wildlife conservation

In 2021, life came full circle for Sahu. She was appointed as Additional Chief Secretary, Department of Environment, Climate Change & Forests, Government of Tamil Nadu, sectors she has always been passionate about.

When she took charge, Sahu’s focus was to chart new pathways for conservation—and look at areas that did not get much attention.

After several brainstorming sessions, field visits and working with frontline workers and experts, she wanted to create a new era of conservation, one that has yielded incredible results in just two years. This, she says, was possible only because of strong political will and pro-active official machinery.

“We were able to notify a new elephant reserve, the Agasthyamalai Elephant Reserve, 20 years after the last one. From just one, our Ramsar (a wetland of international importance under the Ramsar Convention) sites have increased to 13, the highest in India today. We also did something that had never been done before—identifying the areas where animals require immediate attention,” she says.

Under her tenure, India’s first Dugong Conservation Reserve in the Palk Bay area of the Gulf of Mannar, and the Slender Loris Sanctuary in Karur and Dindigul districts, both endangered species, were notified. She also initiated the first-ever project in India for the conservation of the Nilgiri Tahr, besides creating a Wildlife Crime Control Bureau for Tamil Nadu to crack down on illegal animal trade, and poaching and to create widespread awareness about protected animals.

While efforts are being made to reduce the man-animal conflict, Sahu believes it’s a challenging task.

“The conflicts are only going to increase because of habitats getting impacted, water scarcity, increased biotic pressure, development of roads and climate change,” she points out.

While accepting this, Sahu says the first step is to reverse the damage that has already been done.

“We are working with National Agricultural Bank for Rural Development (NABARD) on a Rs 490 crore project for restoration of water bodies, creating water bodies, planting trees and grasses, securing habitats and fighting poaching,” she elaborates.

The second step is to use technology effectively to alert the community in advance and prevent human deaths.

“We have set up WhatsApp groups within local communities where our anti-poaching watchers and forest officials post messages. In Valparai, in association with some NGOs, we have installed sensor-activated warning lights,” she adds.

Sahu says it’s also imperative to talk about animals, in the man-animal conflict, and the loss of their lives.

“We are using AI and ML-based technology in places like Madukkarai in Coimbatore where elephants stray onto railway tracks and are hit. In collaboration with the Railways, we are creating underground passes for elephants so they don’t come onto the track. We are also setting up a surveillance mechanism that will alert the train driver well in advance,” she says. In addition, drones and chain link fences are also used in the process.

She also shares that Rs 11.5 crore was disbursed as compensation last year for crop losses and deaths due to animals.

Yellow bags against single-use plastic

A woman in Rajapalayam with the manjapai (yellow bag). Image courtesty: Supriya Sahu's Twitter feed, @supriyasahuias

On the sustainable front, Sahu speaks of the revival of the humble manjapai (yellow bag) as the traditional alternative to single-use plastic. She initiated the Meendum Manjapai campaign last year when the department installed manjapai vending machines from Koyambedu wholesale market in Chennai. It has now gained popularity across many states in the country as the Thaila ATM or cloth bag ATM.

“I think manjapai is an idea whose time has come. It’s a strong symbol against the culture of single-use plastic and promotes the ‘reduce, recycle, reuse’ concept. For centuries people in Tamil Nadu have been using the manjapai, and it’s a simple but impactful solution,” she says.

On the climate action front, Sahu says, the setting up of the Tamil Nadu Green Climate Company (TNGCC), will drive action as a focal body with three missions – TN Climate Change Mission, TN Green Mission and TN Wetlands Mission.

“Under the Climate Change Mission, the state has selected Coimbatore, Nilgiris, Rameshwaram and Rajapalayam to become carbon-neutral towns. This will include effective management of emissions with industries, waste-to-energy interventions, enhancing the green cover, and more,” she says.

Sahu believes women play a huge role in fighting climate change and promoting sustainability.

“Whether it’s the 80-year-old Veerammal paati, the panchayat president of Tamil Nadu’s first biodiversity site at Arittapatti, or women proudly holding manjapais, women lead the way. Every time, I see such incredible women or hear of them, I post them on social media, so that others can be inspired,” Sahu says.

Edited by Affirunisa Kankudti