These two brothers from a village in Haryana are converting cow dung into biogas to power their factory

The Amrit Fertiliser Plant not only provides enough electricity to power the brothers’ ancestral steel plant, but its organic fertilisers have also benefitted a lot of local farmers, increasing their income by 50 percent.

In Kunjpura village, located in Karnal district, Haryana, Aditya Aggarwal (31) and his older brother Amit Aggarwal (34) run Tee Cee Industries, a steel plant set up by their ancestors in 1984. Along with this, they also run a gaushala that houses 1,200 cows that can no longer produce milk.

The cow shelter was manageable but running the steel plant was turning out to be expensive because they spent a whopping Rs 5 lakh every month on electricity.

The brothers struck upon an idea. Why not run the factory with the biogas produced from cow dung from the shelter and other gaushalas, along with bio and agri-waste like sewage, farm waste, etc?

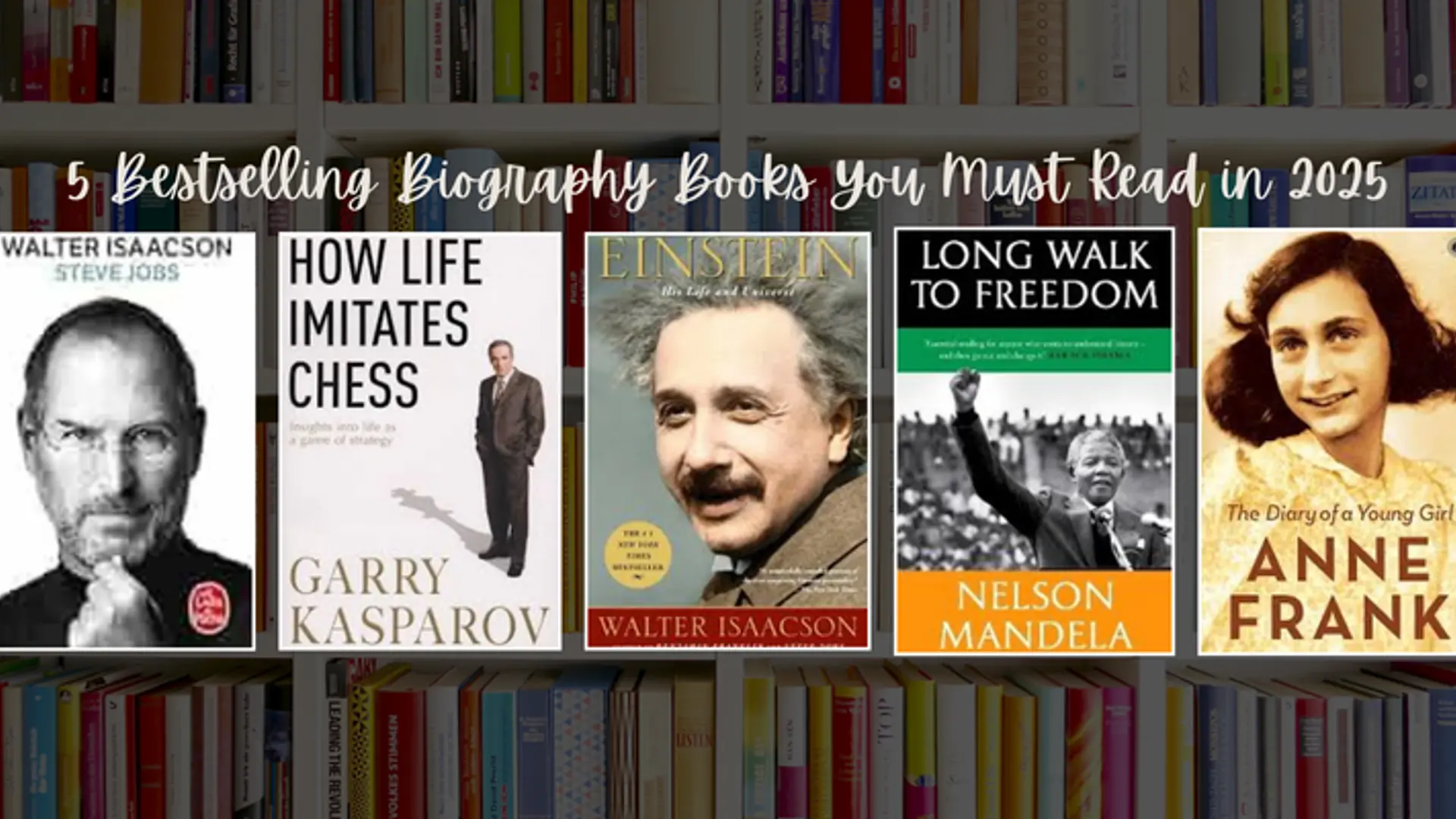

Aditya Aggarwal (centre) along with his elder brother Amit Aggarwal (right) and younger brother Anuj Aggarwal (left) at Amrit Fertilizer biogas plant

This led Aditya and Amit to start Amrit Fertilisers, a biogas project, in 2014, without any government support.

The brothers started off with the production of organic fertilisers by taking organic waste from farmers including sewage and cow dung from their cow shed. This process turned out to be a success, as the farmers who were into sugarcane farming saw a spike in the production - from 300 quintals to 450 quintals in a year.

While producing organic fertilisers in the slurry tank, Aditya also realised that the methane gas released can be used for various purposes like cooking and other activities.

Speaking to SocialStory, Aditya says,

“I searched on Google, watched few videos, and read about a lot of fundamental concepts and principles to construct a biogas plant with the help of my brother.”

At present, the biogas plant produces enough electricity to run and operate their ancestral steel plant.

The eco-friendly solution

The self-funded biogas plant, spread over 5,500 square feet, has produced 18,25,000 units of electricity, and has delivered around 73,000 tonnes of fertilisers to more than 1,000 local farmers by using 36,500 tonnes of cow dung.

A view of the biogas plant

Speaking on the organic fertiliser production, Yashika Singla (37), a graduate in Urban Design from New York, who is a consultant with Amrit Fertilisers, says,

“The fertilisers made from the process are organic and therefore require less water for farming. Also, Aditya and Amit have tested and have had successful results for soil-less farming that further reduces the need for water as compared to conventional farming.”

This has also helped farmers practice organic farming at just 10 percent of the conventional organic farming cost. Also, it has increased their overall income by 50 percent.

Smart processes

Unlike other biogas plants, where the tanks are kept in a linear order, here the tanks are kept on a declining slope. This means each tank, which are half submerged in the ground, were kept in a single declining line.

This method ensures the slurry passes from one tank to another with the help of gravitational force.

Also, when compared to a conventional setup, the plant uses only 50 units of electricity a day against a conventional biogas plant that uses a minimum of 200 units per day. It also has multiple digesters that aid the process.

Amit Aggarwal with delegates from Uganda at their plant

Also, the plant is designed in a way that it is sustainable as it has a minimum operational life of 15 years as compared to 10 years for a conventional biogas plant.

Yashika explains the process in detail.

“It takes 80 days for complete anaerobic digestion, in which microorganisms transform organic matter in wastewater into biogas in the absence of oxygen. This process also includes aerobic digestion, in which oxygen is used to break down organic matter and remove pollutants like nitrogen and phosphorus.”

This total digestion process begins when cow dung, sewerage waste, and vegetable waste are dumped into the tank. The slurry from these produces usable gas, which is then stored in closed tanks.

Later, the residue from the slurry is extracted in dry form, which is transported in carriage tanks, after which it is compressed into usable fertiliser cakes and then supplied to the farmers. Any waste produced from the plant at the end is again fed into the tanks in the initial process.

The plant is so efficient and productive that it produces 2,000 units of electricity per day. This is enough for the steel plant to run for the next 80 days when the next batch of biogas is under production.

The plant uses only 50 units of electricity a day against a conventional biogas plant that uses a minimum of 200 units per day

There are over 1,000 farmers in the Kunjpura village who have benefitted from the biogas plant. The family is well-known and respected in the village for its charitable initiatives, and so there was no obstacle in getting them on board with the idea.

Yashika says, “To get farmers onboard, we don’t charge them anything. Right from collecting fodder, getting vegetable waste, to supplying the farmers with organic fertilisers, we bear the cost of logistics.”

This dual benefit – producing high quality fertilisers and also biogas – by the brothers has received widespread appreciation in the state.

On April 30, 2018, the then Union Minister for Drinking Water and Sanitation, Uma Bharti, launched the GobarDhan scheme on the same lines to manage bio-waste for generating energy.

The way forward

Aditya says they now incur only Rs 35,000 on electricity that is used by the labourers’ accommodation.

Their future plans include expanding the plant’s base area, for which they have already acquired land. Besides, Indraprastha Gas Limited has also come onboard as a customer and will buy the biogas produced by the plant under the SATAT scheme of the Central Government.

(Edited by Rekha Balakrishnan)