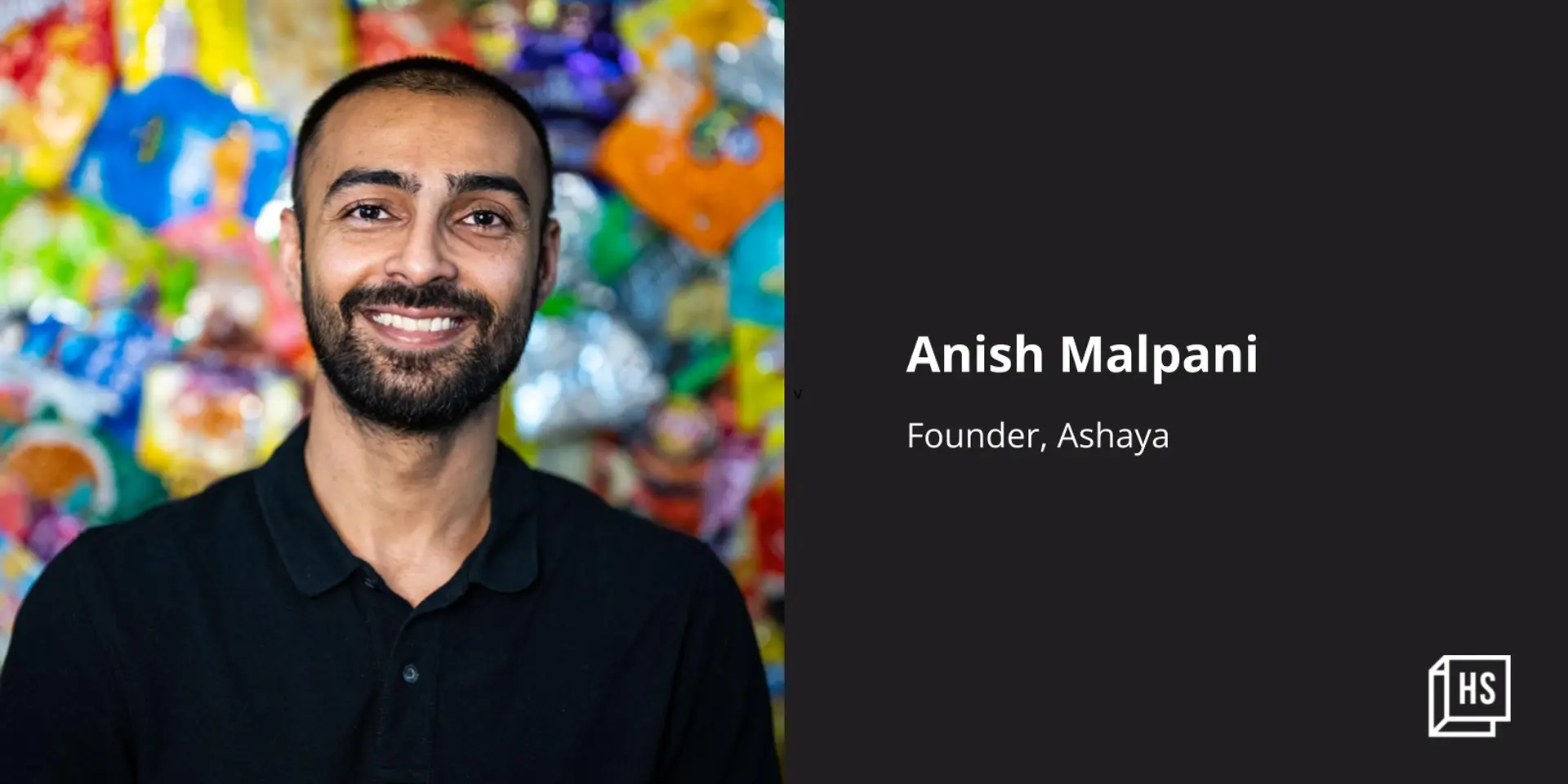

This entrepreneur’s startup makes sunglasses from packets of chips

Anish Malpani’s social startup, Ashaya, has launched Without, a brand of sunglasses that use frames made from multi-layered packaging (MLP) waste such as packets of chips, chocolate wrappers, and others. His value-from-waste policy also aims to empower waste pickers.

A couple of years ago, Anish Malpani was passing through the Chembur landfill in Mumbai that receives tonnes of waste daily. He wondered if any of the waste could be turned into anything of value.

“This is complex problem both environmentally, and socially. But I felt that there could be an economic upside here, because there’s economic value in waste, a value that could be used to empower waste pickers,” the social entrepreneur tells SocialStory.

Anish Malpani and Dr Jitendra Samdani

Malpani was not making a stray observation. He had recently returned to India from the US to focus on poverty alleviation through social enterprise, and this seemed to be a good enough beginning.

Raised in Dubai, Malpani moved to the US to pursue an undergraduate degree in finance and sports management from UT Austin. A conventional career in finance followed, climbing the corporate ladder, applying for a green card, and looking forward to having a family life in the suburbs.

The Great American Dream would have taken off, if not for one niggling thought.

“I was really down and depressed and, on reflection, I believed I needed to do something more meaningful,” he says.

Malpani says it may sound like a cliché, but he wanted to return to India and work on a social enterprise - to build a financially sustainable solution that could create impact at scale.

This laid the foundation for , a Pune-based company that that makes sunglasses from chips packets, and is looking to introduce more products made from MLP (multi-layered packaging) waste that includes chocolate wrappers, chips packets, and more.

Understanding social enterprise

But Malpani didn’t want to be known as “that guy from New York who knows everything and needs nothing”, and so set about understanding the space as much as possible.

“I was lucky to be in Guatemala for a year to work with local entrepreneurs that ranged from those running grocery shops and ice cream stores to complex ones like building fintech solutions. Later, I moved to Nairobi for six months to work with local entrepreneurs again,” he says.

His motive was to understand impact outside India, “get it out of his system”, and then return to his home country. He hadn’t lived in India for almost two decades, only visiting for vacations.

Malpani began by researching poverty in India and says the waste management space interested him for many reasons.

“There were around four million waste pickers who led poor lives, not just from an income perspective, but from a multi-dimensional perspective—right from access to healthcare and education. They work in unhygienic environments and have very little dignity in what they do,” he explains.

Also, 50-80% of waste is not recycled, which leads to a complex problem, on all fronts.

With a small team and an expert, Dr Jitendra Samdani (PhD in electrochemistry), Malpani decided to look for ways to increase the value of waste while understanding the science behind processes. Already, PET bottles or HDP bottles were already being recycled. His aim was to work on problems no one else was working on.

“We chose MLP and started researching from a small lab we set up in Pune. For the first year-and-a-half, we worked on the technology of extracting materials from MPL and converting them into high-quality material.

We closed the first year with close to a 1,000 experiments and found that we could extract a higher quality material from the worst kind of plastic waste,” Malpani says.

It chemo-mechanically extracts materials using a patent-pending technology to convert them into high quality products.

Best out of waste

The team wearing Without sunglasses

The first thought was to sell the material but the problem was no one would want to buy 10 kilos of material; they would look at tonnes. The lab did not have capacity to produce at scale, yet. Even if they sold the material, they would hardly break even, given the quantity.

The next thought was how to fashion products that would actually sell. Working with focus groups, and after many hours of brainstorming, the Ashaya team made a list of 400 products that it ultimately shortlisted to around 70.

“Sunglass frames seemed to be the right idea, at the product level. Sustainable, scalable. and would offer better margins from an economics perspective. It would also have intricacy and finesse, was less complex, and would also be a cool product to launch,” Malpani elaborates.

Chips packets, he says, are not easy to break down—there are many layers including metal and cellulose. While a lot of sunglass frames are made from recycled material, Malpani claims they are the first to produce them from MLP waste. The lenses are bought from a local supplier, but the plan is also to source sustainable lenses in the long run.

Ashaya announced its pilot project this month – the Without sunglasses on Twitter and LinkedIn. In just four days, he received more than 500 orders, and the count is still on.

The sunglasses are UV polarised, durable, and bendy. They cost around Rs 1,000 for a pair. They weigh just 26 grammes, bend and adapt easily. They come in unisex designs, are medium-sized in charcoal black colour for now. One sunglass is made from five recycled chips packets.

Value from a multi-dimensional perspective

According to Malpani, the team can produce 30-50 sunglasses in their lab in Pune in a day. The social enterprise part of it is interesting in many ways.

“We are focused on the metric called multi-dimensional poverty index, looking at waste from a multi-dimensional perspective by offering waste pickers an income, access to healthcare, education and a decent living. That’s our long-term goal,” he says.

In the short run, 10% of all sales will go towards scholarships of children of waste pickers. It also pays a premium for the waste, at Rs 6 per kilo, higher than what they are usually paid. Ashaya is currently working with five waste pickers and hopes to include more as the business scales. It has also opened bank accounts for informal workers.

So far, Malpani has used his own savings and grants from various organisations like Startup India Seed Fund through AIC ISB, Social Alpha Nation & H&M Foundation, and the Incubation Network to work on Ashaya.

“Our next step is to take this technology from the lab to market, try and scale. We want to recycle at least 500 kg of MLP in a day. Our goal is build decentralised processing units to incorporate waste, and along the way build financially, environmentally and economical solutions,” he says.

Ashaya has also received B2B requests but has had to decline because “it needs to scale”.

Malpani is talking to potential impact investors and says it’s tough. “Our venture requires patient capital from investors and finding them is difficult. Everyone seems to be interested but when it comes to actually writing the cheque, it’s a lot more complex,” he says.

Edited by Teja Lele