Sexual trauma and the journey towards healing

This article explores the complexities of sexual trauma, the challenges along the path to recovery, and how trauma-informed mental health professionals are helping people identify and heal their wounds and lead fuller lives as adults.

Trigger warning: The story contains references to sexual trauma, caste and gender-based trauma, and child sexual abuse.

In her teens, Seema* had a compulsive feeling that she was being watched by everyone as she walked out on the road. As an adult, she realised that this feeling was exacerbated on the days she experienced a conflict situation at work or with her partner, making her feel small, shameful and defenceless.

The feeling was typically followed by a sense of dread and a stinging pain in her pelvic region and chest.

While Seema, who is now a college professor in Chennai, knew these were the symptoms of an impending panic attack, it wasn’t until a year ago that she understood the underlying cause behind this recurrent trauma response.

After several sessions with her therapist, Seema’s experiences as an adult were eventually traced back to an adverse event in her childhood—when she was hooted at and groped by some passersby on the road.

“My therapist and I discovered that the frightening lack of self-worth and confidence I experienced while navigating difficult relationship dynamics as an adult were the exact same feelings I had experienced as a 14-year-old walking out of home that day,” she shares.

In her journey towards healing and reconciliation, Seema has been practising yoga and mind-body exercises to face her trauma and overcome it.

Although it is a work in progress, these exercises have helped her reconcile with what had happened and not mechanically block out the memories.

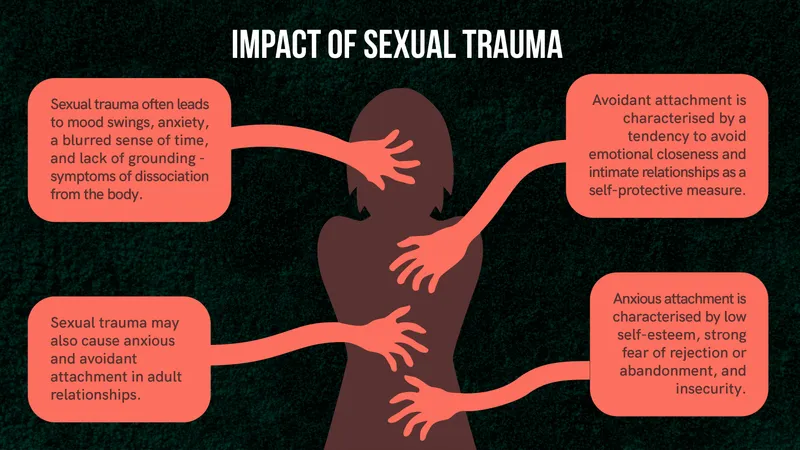

A majority of survivors cope with traumatic events by mentally shutting down memories of them. This, according to studies, puts the load on the body to process these events, leading to a whole range of effects including muscle tension, fatigue, and chronic physical and mental health conditions.

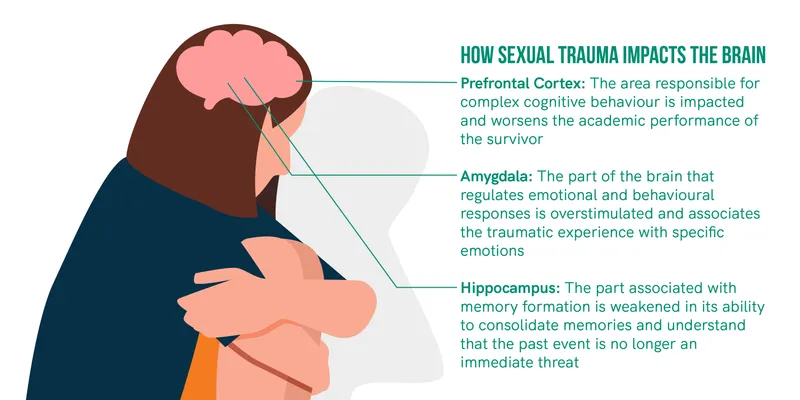

While it can be frustrating to connect crippling behavioural patterns in adulthood to different degrees of sexual trauma experienced in childhood, several studies and research point out that sexual trauma affects the brain in definitive ways.

A 2021 study by the University of Pittsburgh’s Graduate School of Public Health found that people with a history of sexual assault face the risk of brain damage and cognitive decline.

For professionals working to heal the wounds of sexual trauma, these aren’t just academic records but powerful medical, psychological and psychosocial knowledge that must reach people for them to become aware of their experiences and begin healing.

A growing tribe of trauma-informed psychotherapists is spreading awareness about sexual trauma, helping people decode what research has been saying for years, and supporting them in reclaiming their lives.

Social spectrum

Sexual trauma, in all its complexity, has become a vital aspect of mental health research and service today, perhaps more so with respect to women and gender minorities.

According to sex and wellness therapists, the stigma, shame and resistance surrounding sex and sexuality in the country have led to several mental health conditions—including clinical depression, PTSD, panic disorder and substance abuse—being undiagnosed, thus impeding survivors from leading full, productive lives.

Among the many things that the ‘Me Too’ movement has brought to the surface is the realisation that many people in the country have experienced sexual violation in some form or the other in their lives. Subsequently, this understanding has become central to the discourse surrounding workplace ethics, social justice, and feminist and LGBTQIA+ movements.

But, it's as important to understand the social and cultural aspects at play and how they can impact one’s view of sex and sexuality, say experts.

Sexual oppression and regression have been hardwired into our cultural consciousness for years—and this is something that mental and sexual health professional Neha Bhat is addressing in detail.

In her free online masterclass in association with sexual wellness company That Sassy Thing, Bhat calls out the misconceptions and fallacies that have endured over generations of patriarchal order controlling the sexuality of women and gender minorities.

“You could have watched something and had a shaky sexual experience— that’s sexual trauma. You could have been disrespected on the street—that’s sexual trauma. You could have been whistled at in a movie theatre—that’s also sexual trauma. It doesn’t always have to be as intense and legally validated as rape,” explains Bhat, who is spreading awareness on the subject and the ways to recover using arts-based therapy.

Adding to what is an already difficult journey is that shaming is a big part of Indian culture and stays with you for a long time, says Delhi-based clinical psychologist Ashmeet Kaur.

In her practice, Kaur meets newly married Indian women who feel ashamed to face their parents after their first sexual intercourse with their husbands. She attributes this to the early conditioning in girls to associate shame with everything related to their bodies and sexuality.

“Girls are made to feel ashamed about everything from drying their undergarments in the open to buying sanitary napkins, from having a boyfriend to feeling sexual desire,” says Kaur.

As they pick up these social cues of what’s ‘right’ and ‘wrong’, they grow up feeling shameful within and about their bodies.

“As adults, they cannot enjoy intercourse. Some struggle with conditions like vaginismus—a type of sexual dysfunction caused by the body’s automatic reaction to the fear of vaginal penetration,” she adds.

It is critical to understand that in the sexual culture of India—the world’s most populous nation—the impact of sexual violence plays out in varying degrees and across time spans, compounded by gender, caste and class hierarchies.

For instance, rape and sexual violence against Dalit women are often followed by other forms of violence such as gang rape, murder, assault, kidnapping, social boycott, arson, witch hunting, and abetment to suicide. Caste dominance, land disputes, and factional rivalry often lead up to sexual crimes.

The long and often futile road to justice can leave a lasting impact on the nervous system, resulting in intergenerational trauma in Dalit victims of sexual violence.

When a regulated nervous system experiences stress, it returns to a normal state when the threat has passed. But when a traumatic event pushes the nervous system beyond its ability to regulate itself, it remains overstimulated for years or even decades after the event.

In her book The Trauma of Caste, Indian-American Dalit rights activist Thenmozhi Soundararajan shares how both the oppressor and the oppressed can heal the wounds of caste and transform collective suffering.

Her suggestions include embodiment exercises, reflections, and meditations to help readers explore their own relationship to caste and marginalisation.

Even the compulsion among women to be hyper-vigilant all the time results in the kind of cognitive load that’s detrimental to their body and their mind’s ability to relax or even understand leisure, says Hyderabad-based consultant psychologist and mental health educator Soumya Madabhushi.

“When we ask women if they would take a dark alley which is a shorter route, or a longer, better-lit and populated route back home, they always choose the latter. They have to always have their SOS contacts handy. These things may have been normalised but they lead to disruptions in mental and emotional health with time,” she says.

Several people from the LGBTQIA+ community too become victims of sexual violence due to social stigma.

Many community members—especially those from small towns and rural areas—are forced to meet people they find on dating apps discreetly. A lot of them fall prey to catfishing and become victims of extortion, sexual violence, and, as a result, sexual trauma.

The path to healing

The path to change and recovery is fraught with several challenges—mental, physical, and emotional—and understandably so. It involves identifying stereotypes, understanding boundaries, and being aware of the dynamics of trauma and oppression.

Bhat takes the example of her client, Indira*, who was sexually abused as a child and grew up thinking that the event had no impact on her until she turned 21, when she realised that she had violated her girlfriend’s boundaries during sex.

“While crossing her girlfriend’s boundaries today, Indira did not realise that someone very far back in her trauma history had violated her sexually and did not give her body a chance to figure out what her own boundaries were,” Bhat explains.

When we think of child sexual abuse, we often think of a ghastly scenario wherein a stereotypical rapist hurts a child. Then an NGO comes into the picture, informs the family, and saves the child from the perpetrator.

“It’s not that these things don’t happen, but a lot of perpetrators are people we know in our families and work settings who have some familiarity with the survivor or victim and manipulate that relationship,” says Bhat.

“So, it’s not surprising that Indira blocked out this memory from her childhood, as it did not match the stereotype of rapists that we carry in our minds. This is also why a lot of us don’t take sexual violence seriously,” she adds.

Before Bhat helped Indira heal, she had to unlearn some ideas herself. Like many professionals in the field, she had been trained to have a binary view of how survivors look and who the perpetrators are—from schools, textbooks and the general narrative.

“When this person came to me, they presented a very deep and painful reality—that many of us have survived and also perpetrated sexual violence and trauma,” says Bhat.

“I’m not saying they have perpetrated malicious harm but we are all part of a society that’s both oppressed and oppressive. We live in these intersections.”

And these intersections transcend to the realm of dating as well, where people do not understand the concept of consent, how to ask for it, and what feels good to them and the other, she adds.

In her work, Bhat explores sexual trauma and its connection to adult sexual, relational, romantic and aromantic relationship dynamics of survivors.

Trauma isn’t solely about the events themselves but about how an individual’s nervous system processes those events, say mental health professionals.

“Healing trauma at its core involves resourcing and rewiring the nervous system, guiding it from a survival state toward a restored baseline of regulation,” says Kaur.

American psychiatrists and researchers Bessel Van Der Kolk and Judith Lewis Herman have put forth trauma-informed approaches to healing in their seminal works The Body Keeps the Score and Trauma and Recovery, respectively.

Their work has also inspired the emergence of a whole lot of neurobiological research to understand how trauma impacts the mind and the nervous system and therefore the body.

Focused trauma work guides mental health professionals to help people process distressing events and the lasting experience of trauma following those events, subsequently enabling them to build secure attachment in adult relationships.

This translates to the ability to appreciate one’s own self-worth, be oneself in relationships and be comfortable in the skin.

Alternative techniques

Trauma-informed psychotherapists and mental health professionals today also advocate somatic exercises, breathwork, trauma-centred movement, arts-based therapy, depth-oriented psychotherapy, psychodrama, and other methods to help survivors identify, heal and recover from sexual trauma and lead fuller lives as adults.

Somatic therapy uses mind-body techniques to release pent-up tension and helps repair a survivor’s internal processing of trauma by rebuilding the lost mind-body connection. The repair occurs in non-threatening social interactions, providing space for the individual to rewire their defensive responses.

Arts therapy involves creating objects using materials such paint, fabric and beads in the presence of a therapist, to process the pain experienced from sexual harm, while depth-oriented psychotherapy is a long–term practice that brings to light parts of the self that are hidden in the unconscious mind.

These methods help build better coping mechanisms and regulate one’s nervous system, say experts.

“When you take steps towards your individual process of healing, recovery, resilience and empowerment, please know that it is going to be uncomfortable. So, take it in digestible bite-sized pieces that make sense to you,” advises Bhat.

“I don’t necessarily associate healing with calmness or the idea of a perfect survivor. For me, healing is a way to come back to sensitisation—to a place in my body that feels alive and true to me.”

(*Names have been changed to protect identities.)

Edited by Swetha Kannan