Indian seniors break barriers to find love in their silver years

A growing number of seniors are batting social stigma and prejudice to assert their right to companionship, find love, and overcome loneliness and isolation in old age.

Sadhana Savagave’s husband from her first marriage was diagnosed with and succumbed to cancer—all in a matter of four months.

The emotional turmoil and loneliness that followed the abrupt vacuum in her life three years ago convinced Sadhana that she would not go through the rest of her life alone.

“Loneliness can hit anyone at any time. It’s a lot more pervasive than people think,” says the 57-year-old former businesswoman from Pune.

“I wanted someone in the house I could hear, talk my heart out to, and travel with,” she adds.

Many elderly in the country resonate with the need for a companion as they go through life’s twilight years.

A Lancet study from 2020 says life expectancy in India has risen by a whole decade–from 59.6 years in 1990 to 70.8 years in 2019.

As of July 2022, the country was home to 149 million people aged 60 years and above, comprising close to 10.5% of the total population, says a study by the United Nations Populations Fund. The study preempts India’s elderly population to double by 2050, overtaking even the number of children in the country.

Alongside the growing elderly population in the country, there is also an increasing incidence of loneliness and isolation in old age, which can lead to depression, cognitive decline, dementia and high blood pressure.

In July last year, hygiene products manufacturer PAN Healthcare studied 10,000 people across 10 Indian cities and revealed that more than 65% of them were lonely.

Seventy-year-old Manimekalai (name changed on request) of Chennai, who has been a homemaker all her life, lost her husband to a heart attack four years ago. Manimekalai, who continues to live with her ailing mother-in-law, says life has only been getting harder without her husband.

Hailing from an orthodox family, it took her years to even recognise that the emptiness and disillusion she was feeling was actually loneliness.

Madhav Damle, a 68-year-old resident of Pune, identified this over a decade ago at the senior home he was then running. He saw that, as children in the education hub studied well and secured white collar jobs abroad, senior parents were left behind—many of them widowed and ailing.

“We saw that if a senior citizen lost their spouse before or at the age of 60, they had a whole decade or more to go on. And they have to do so without a companion,” he points out.

This realisation led Damle to start Happy Seniors—a matchmaking platform for silver citizens in 2012—which till date has united 75 senior couples.

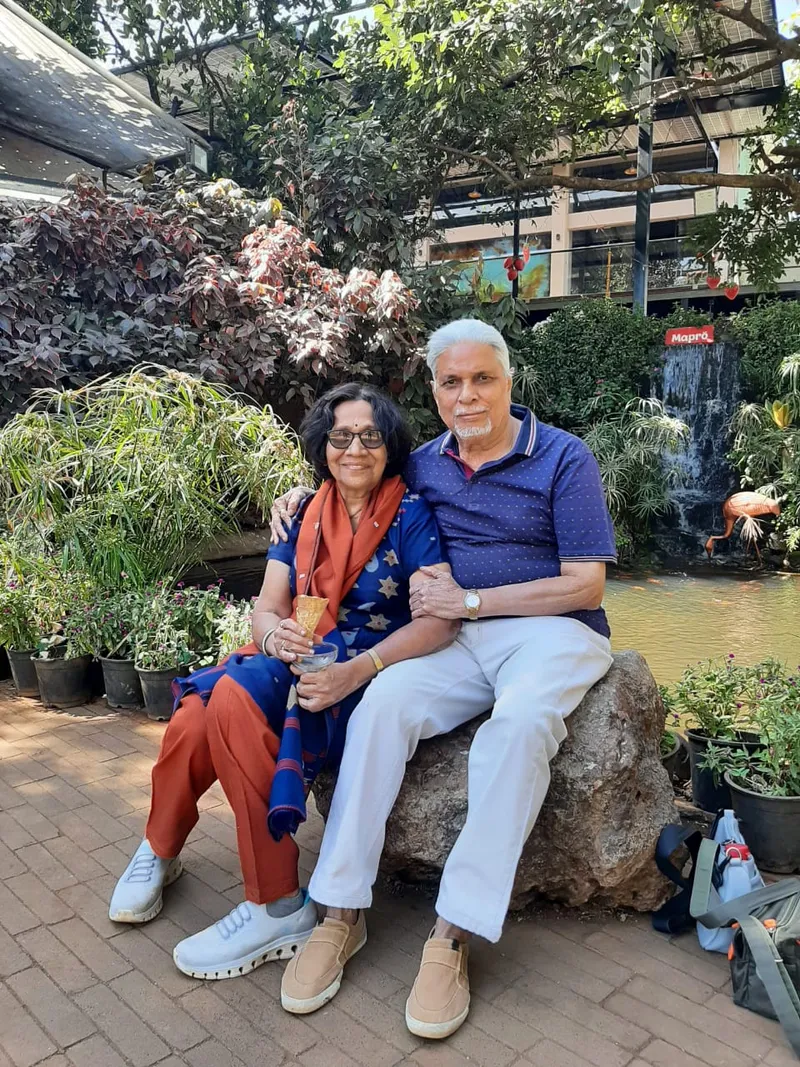

Sadhana and her husband Nitin Ganpatrao Savagave are one of them.

Starting a new chapter

Nitin, the principal of an engineering college in Maharashtra, got divorced in 2016. He has a son from his previous marriage.

His family wished that he would remarry but it wasn’t until 2020, when he met Sadhana at Damle’s office, that he decided to start a new chapter in his life.

Nitin and Sadhana Savagave got married when they were in their mid-fifties.

The couple got married in a traditional ceremony on March 19, 2020, days before the first Covid-19 lockdown.

When it comes to finding a partner, seniors seem to be very clear and particular about what they want, says Damle.

“Most men want women who haven’t crossed 50, can cook well, and are conventionally good-looking, and women want men who have been in high positions at work, are financially well off, and can take them on trips,” he elaborates.

Most of the time, they struggle with the hangover from their previous relationship.

“We counsel them to be open-minded while seeking companionship again in life. We also encourage them to live in for a few months to see if they and their families get along, and then take a call about marriage,” says Damle.

On some rare occasions, children living abroad also get in touch with the matchmaking service to find partners for their old parents in India, so that they are not lonely or depressed.

Before they begin dating or living together, Damle encourages potential couples to sign an agreement on everything from finances and household responsibilities to the nature of their relationship, so that there is little room for conflict and confusion at this stage in their lives.

Legal and social aspects

The Supreme Court has declared live-in relationships in India to be legal, and, in recent years, it has also brought into this purview laws regarding domestic violence.

However, despite legal sanction, senior citizens have to deal with cultural factors, social acceptance, and the stigma associated with remarriage at old age. Besides these, there is also the issue of inheritance, which children don’t want to deal with at a time in life when they themselves are married and parents to young children.

As per the Indian Succession Act of 1925, a widower is entitled to one-third property of the deceased spouse and, in the case of an inter-faith marriage, the wife is entitled to inheritance as per the personal laws applicable to the religion of her husband.

Therefore, a growing number of people seeking late-life relationships in India are drawn to dating or live-in relationships to avoid these complexities and the fight for acceptance. Dating, without the pressure of marriage, also gives them the advantage of being discreet and being in a relationship on their own terms.

In the last month, Indian dating app Quack Quack witnessed a steady rise in the number of senior users.

A recent online survey conducted by Quack Quack, with 6,000 participants between 50 to 68 years of age from metros and smaller cities, revealed that 38% of seniors from Tier I cities felt that society would rather have them join golf clubs or yoga classes than be on a dating site. It also said that 34% of male daters from Tier II cities who were widowed, divorced or never married found solace in dating, and 27% of women above 50 sought companionship over love.

The study also revealed that 8% of its participants had found love on the app; 12% of women said they had found friends like family and urged more seniors to start using dating and friendship apps.

“We see many of our senior users looking for companionship, not necessarily romantic or strictly platonic, nor with an end goal in sight. The connection, however, has to be genuine, and this requirement is unique to this age group,” says Ravi Mittal, Founder and CEO of Quack Quack.

Battling social prejudice

Asserting one’s right to security and companionship may be legally acceptable, but for scores of elderly—especially women—a relationship in their twilight years still remains a taboo in society. Cultural stigma and their associated role as nurturers and caregivers keep them from making independent choices.

When Sadhana was seeking companionship, she faced strong opposition from her two children, who felt that she need not seek support outside.

“But being dependent on children is very different from having a partner to come back home to and share your lived experiences with. I was very determined to do this for myself,” she says.

Septuagenarians from Pune, Asawari Kulkarni and Anil Yardi met in 2015 through Happy Seniors and dated for 10 months before they moved in together. They were 62 then.

Asawari Kulkarni and Anil Yardi met in 2015 through Happy Seniors and dated for 10 months before they moved in together.

It has been seven years hence and they say they wouldn’t have it any other way.

Kulkarni retied from service at LIC in 2012. She had been on her own since 1997, when her husband passed away.

"I didn't feel the pinch of living alone while I was working. After retirement, my social activities also came down," she says.

"On the days I fell sick, my grief became worse," she adds.

Kulkarni saw an ad about the Happy Seniors matchmaking platform and went for a meetup where she met Yardi for the first time.

"We instantly hit it off. We also consciously decided we won't get married and live together instead. We wanted it to be simple if things didn't work out and also avoid legalities," she says.

Although their families were opposed to their decision initially, they have now made peace with the couple’s choice as they stood their ground and made their partnership public.

But not everyone is able to take this step with courage and conviction.

Manimekalai says at least two men in her lineage have remarried after losing their wives to illnesses. But it is almost a sacrilege if a woman entertains the same thought, she says.

“My counsellor suggested that I try to find a companion. I feel it isn’t such a bad idea, but I cannot dare speak to my family about it,” says Manimekalai, who got married when she was 20 years old.

“I’m afraid the whole family structure and life that my husband and I built together will collapse if I seek out a companion now,” she adds.

Kolkata-based consultant psychiatrist Dr Neelanjana Paul says many children are happy to connect their old parents to prayer groups, sports clubs, and senior homes but don’t extend the same sensitivity when they want to find love or companionship.

While the community plays a big role in helping elderly fight isolation, that is not enough.

“Senior citizens tend to lose their purpose in life when they lose their partners whom they have lived, argued, reared children, and run the house with,” says Dr Paul. So, it’s natural that they feel the need for someone to touch them, take a personal interest in their health and wellbeing, and have conversations with them.

She reiterates, “This is a fundamental need in all of us. Depriving someone—especially in their old age—of this right isn’t just unfair, it is also cruel.”

Edited by Swetha Kannan and Suman Singh