This city-bred youth gave up his job to bring an unknown village on the travel map

Situated at an altitude of 7,800 feet in the upper Garhwal region of Uttarakhand, Kalap is a village that lies forgotten in time. It is 200 km by road from Dehradun. But there is no approach road to the village, so a visitor has to walk 11 kms among pine and deodar forests before arriving at Kalap. The village overlooks a gorge cut open by the roaring River Supin, and provides a breathtaking view of the surrounding Himalayan range.

Thirty-two-year-old Anand Shankar stumbled upon the village in 2007 while he was working as a journalist. “I had kind of made up my mind when I was working in Delhi that one day I will move and work in the outdoors, preferably the Himalayas,” says Anand, who quit his job around 2010 and moved to Bengaluru to start an adventure tour company. “I was fed up with working under middle management editors in newspapers.”

Unfortunately, the adventure business did not take off. But in 2013, Anand went to Kalap again. But this time, instead of being awestruck by the natural beauty around, he realised that because of their isolation, the villagers could not access even the basic necessities of life. There was not a single clinic up there. “When a 70-year-old woman fell at my feet to thank me for a paracetamol tablet, it made me realise how badly we need essential services like healthcare in the Himalayas,” he adds.

This one particular incident did not let him sleep. So he sought recourse to the one source that all urbanites turn to in time of need – Facebook. He appealed for help from doctors who would be ready to go and give a free checkup to the villagers in Kalap. Someone responded and thus started Anand’s tryst with destiny.

The population of Kalap is around 500. The main village is home to about 300 people while the rest of the population lives in the four outlying settlements of Karba, Unani, Jhai, and Dhawla.

Anand says he could no longer just turn back after this. “I had to set up a formal mechanism to structure work. I realised it was going to be beyond my financial means, so I set up a trust, an NGO, the Kalap Trust,” he says. “We are sustained purely by crowdsourcing funds from India. People sponsor children in our school and contribute towards the functioning of our clinic.”

There is one government-run school in the village but is woefully inadequate and dysfunctional. The trust has set up a Montessori-cum-primary ‘after school’ in the village. “Youth from the village have been appointed as assistant to the teaching professional, and the Trust is willing to fund his/her development into a qualified teaching professional in the future to serve the needs of the community.”

Besides basic healthcare, Anand also realised that the children suffered from various nutritional disorders. The trust provides nutritious multi-vitamin, high-protein evening snack to address this problem.

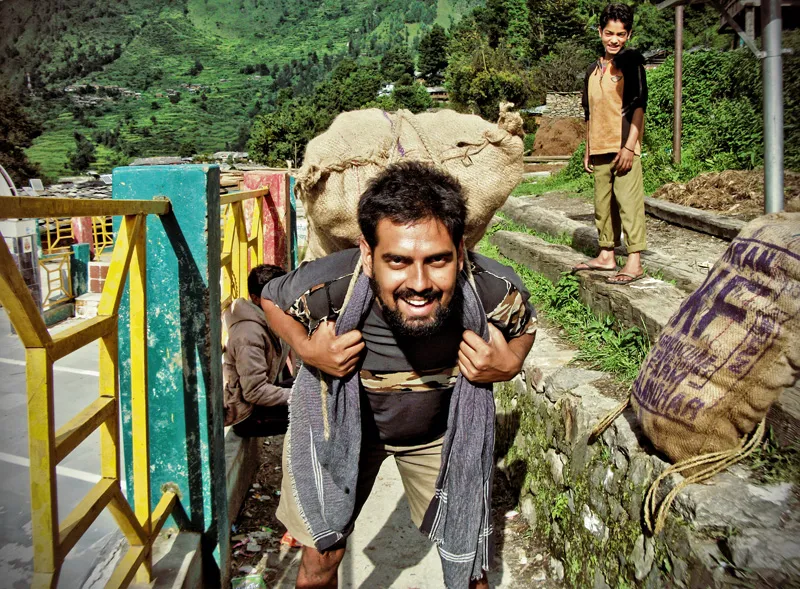

To generate employment for the local population, Anand is using responsible tourism. He trains local youth as trekking guides. Tourists are encouraged to stay with the villagers and the concept of homestays is being popularised.

Last year, the Trust set up a free clinic to deal with two longstanding health care crises – tuberculosis and nutritional disorders – with special emphasis on the vulnerable population – children, pregnant women, and the elderly. Dr Nandana Acharjee is a full-time doctor at the clinic.

There is a serious lack of access to reliable electricity at Kalap, which impacts the quality of life of the community and restricts livelihood options. To solve this issue, the Trust decided to partner with M/s E-Hands Energy Private Limited to deploy a renewable energy mini-grid for the village.

The grid is a ‘for profit’ initiative, where the community pays for the electricity consumed. Two local youth have been empowered with employment through ownership and maintenance of the grid. On June 30, 2015, Phase I of the grid, 2 Kw, went live. 20 homes were powered entirely by solar power.

Anand comes from a family that has “no history of entrepreneurship or doing anything remotely unconventional. So obviously, the reception to my ideas has never been great. They have gotten used to it,” Anand says, replying to how his family received his decision to give up a life in the city and move to the hills.

But his biggest challenges have been “everything from the remote location and terrain to a regulatory environment that views non-profits with suspicion by default.”

Anand has set up the Kalap Trust office in Dehradun, where he also lives now. He visits the village every few days. He says that working for the past three years in Kalap has taught him that one-size does not fit all. “Service delivery models have to be local,” he says.

“Uttarakhand is spectacular but ecologically fragile part of India. Its remoteness and challenging terrain have always made it difficult for its inhabitants to earn a livelihood. Kalap is a small hamlet whose people need new skill sets and ideas to integrate into the economy at large. Life at Kalap is unique and sustainable, and it is critical that the community does not lose its future generations,” adds Anand.

You can support the initiatives of the trust at www.kalaptrust.org/donate

(All pictures courtesy Kalap Trust)