This founder from Rajsamand is showing there is more to agritech than an app for farmers

The challenges plaguing the agriculture sector are many but information asymmetry is the biggest. FarmGuide is solving the problem through digitisation, crop advisory, image processing, and data analytics.

At a Glance

Startup: FarmGuide

Founder: Nikhil Toshniwal

Year it was founded: 2016

Where is it based: Gurgaon

The problem it solves: FarmGuide aims to solve information asymmetry in the agriculture sector through digitisation, crop advisory, image processing, and data analytics

Sector: Agritech

Funding raised: Rs 7.5 crore in seed funding

Nikhil Toshniwal was told there is no ‘virality’ in agritech. He was warned that the struggle to scale will be doubled if he ventured into this sector.

But 25-year-old Nikhil had already made up his mind. Since his second year at the IIT Delhi, he had started visiting farms and villages to talk to farmers and understand their challenges. In 2013, he got an opportunity to interact with Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus as a Grameen Bank intern where he worked as a trainee on microfinance in rural areas.

Nikhil, a 2014 IIT-Delhi alumnus and a diploma holder in social entrepreneurship from Norwegian University of Science and Technology, comes from Rajsamand town in Rajasthan.

During his research in his hometown and across India, while talking to farmers and other stakeholders in the agriculture ecosystem, he realised that the asymmetry in information and communication was the biggest challenge.

Over a phone call from Gurgaon, where his startup FarmGuide is now headquartered, Nikhil tells me, “Farmers have a lot of information, as do seed retailers, machinery guys, and the insurance agencies. But there is no scientific exchange of this information. For example, a seed retailer wants the farmer to purchase the seed that is available on his shelves rather than what the farmer is looking for. Similarly, with the type of fertiliser to be used. Insurance companies, too, want the farmer to grow the crop that they are insuring. So, the seed, the machinery, the finance, and the insurance -- all these parties want the farmer to grow the crop that is in their interest.”

This is not so much as an issue of corruption as it is of a broken link in the chain of communication. “One thing was clear,” says Nikhil, adding, “We had to look for a simple tech-based solution to solve such a complex problem.”

What does FarmGuide do?

The challenges plaguing the agriculture sector are many. Besides issues like information asymmetry, there’s the absence of integrated dataset, unreliable data, problems with crop yield estimation, crop identification, land usage patterns, timely settlement of insurance claims, and lack of internet penetration.

FarmGuide, through its digitised system of automated web and mobile platforms, is capturing real-time data for reliable databases that can be analysed and used at the field level for risk analysis, market distribution, and effective agricultural policy formulation. They use Information Communication Technology to offer customised advisory to individual farmers through an in-house developed IVRS in regional languages.

Nikhil’s aim is to be the “Google of agricultural technologies” and meet the requirements of different stakeholders.

Home ground advantage

“In order to provide our solutions to the maximum number of farmers, we identified that the government had to be the medium,” he adds.

But before he started the rounds of the corridors of power, Nikhil began by digitising the information of 1,400 farmers in his hometown of Rajsamand district. “Since I was from that area, I had an understanding of the complexities and needs of farmers,” he says.

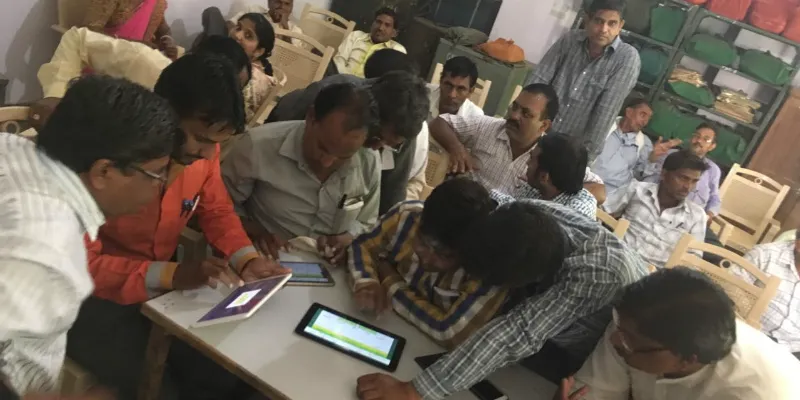

He developed the Farm Registration app, a field app for farmer data collection. Following multiple interactions with farmers and the sarpanch, he created a digital map of the panchayat area with 1,400 mapped fields complete with GPS coordinates and farmer profiles.

“Over the course of three months, I tried to understand the essence of what the farmers, bankers, insurance, and seed providers need to determine the type of datasets that would be required to solve the problems that were preventing the sector from flourishing,” he says.

Interestingly, while running the pilot, Nikhil’s determination and technology caught the attention of Neeraj Sharma, FarmGuide’s angel investor, who put in a seed fund of Rs 7.5 crore.

The business model

FarmGuide has a B2B, Software-as-a-Service business model with technology, market research, and forecasting as its products. “The government and private players are the potential buyers of our tech products. The services offered to farmers are on a pro bono basis. This business model has enabled us to reach the largest agricultural datasets, be it soil information, farmer level data, or yield estimation data,” adds Nikhil.

They follow a ‘Pay-As-You-Use’ model and service-based payment methods. Nikhil explains,

Our product architecture is based on the foundation that we develop a central system upon which we offer simple tools that can be operated by a person completely alien to the technology.

This is how they developed their digital solution for Girdawari, the largest-ever data collection system for harvest inspection. For this inspection, patwaris (revenue officers) have to visit each and every field under them to record land usage patterns twice a year on a massive ledger that is over 60 years old. This has led to digital harvest estimation system and data reconciliation, which is fundamental for creating harvest reports.

“Now, with digital Girdawari in Rajasthan, human error and data duplication has been nullified, and the entire process can be centrally monitored by the different levels within the administration,” adds Nikhil.

This has also reduced the government costs for Girdawari. Moreover, 70 lakh hectares are now connected to Aadhaar in Rajasthan.

But before he started working with the Rajasthan government, Nikhil was grilled for three hours by top officials of the Rajasthan government. “They heard me out and said, ‘you are building a parallel government.’ Though it was said in jest, I took that as a compliment. It meant that my idea was validated,” Nikhil tells me.

He went on to build a system to completely digitise the entire crop insurance process, which was also paper-based and took over three months just to create a policy for farmers who remain clueless about the stages of insurance.

“Using our system, the farmers were informed by SMS about the status of their application,” he adds. Creation of the online crop insurance portal for Rajasthan led to a reduction in administrative expenses, increased transparency, and made the system more accountable to farmer needs. Integration with land records and Aadhaar led to the successful creation of 24.1 lakh policies in Rabi 2016-17, 55.2 lakh policies in Kharif 2017 and 14.6 lakh policies in Rabi 2017-18 in the state. The portal also streamlined the entire process of crop insurance from crop notification to claim settlement in a timely manner.

The impact of FarmGuide’s work in Rajasthan was recognised by the Central government, which chose the startup to develop and maintain the All India Crop Insurance website - Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana - for three years.

FarmGuide has now grown to a 60-member-strong team. “Most of our tech experts are from the IITs and NITs working in various fields ranging from agricultural ground research to computer-based machine learning,” Nikhil adds.

Market ripe for precision agriculture

Food and agribusiness is a $5 trillion dollar market globally and is growing, according to a McKinsey report. Farming in India is worth $370.7 billion and contributes 14.8 percent towards the national GDP.

A strong emphasis on sustainable development has led to the emergence of precision agriculture technologies across the world. The market is estimated to reach $7.6 billion by 2022 at a CAGR of 12.7 percent over the forecast period.

While the total market size for digital-based agricultural services is expected to grow at a CAGR of 12.2 percent between 2014 and 2020 to reach $4.55 billion, according to Accenture.

A number of agritech startups in India have emerged in the past that are striving to change the agricultural ecosystem. Given the market potential for precision agriculture, it would do well for all of them to collaborate. For, if truth be told, there is no ‘virality’ in agriculture. But collaboration could ensure scale and growth for all.

“We have battled the popular perception that there is no virality in agriculture and there can’t be a singular solution to complex issues. It has been a massive endeavour to train all users, including patwaris, bankers, insurance, and government officials to use our products, but we created a solution that did not change the fundamental process. This helped ease the users’ transition from the previous cumbersome practice to the digital platform,” says Nikhil.

Hopefully, FarmGuide's datasets will ensure that other agritech startups and companies or State governments do not spend precious funds and man-hours building their datasets from scratch, and for this, Nikhil says he is open to collaborating with other startups.