Entrepreneurs need to design for ‘extreme affordability’ to create real impact in India: Roopa Kudva of Omidyar Network India

Late last year, Omidyar Network announced a change in strategy, spinning off some of its well-established initiatives as independent entities – one for emerging technology (Spero), another for governance and citizen engagement (Luminate), and yet another for financial inclusion (Flourish).

Given the complex nuances in a market like India, Omidyar Network India (ONI) too became an autonomous entity. This means that it continues to focus on the six areas that the parent company does, but makes independent decisions, sometimes even co-investing in an organisation along with Flourish or Luminate.

YourStory caught up with ONI’s Managing Director Roopa Kudva to find out more. Roopa is well known for having made an unusual transition at the peak of her career – switching from being the CEO of one of India’s biggest financial services company to a global philanthropic investor.

She talks about the type of social impact ONI is seeking to create and how such impact can be measured beyond the standard metric of lives affected and create infrastructure that addresses urgent needs like data security and privacy. And how such efforts can meet the expectations of a young and aspirational India. Here are edited excerpts.

Roopa Kudva, Managing Director of Omidyar Network India

Edited excerpts of the interview:

YourStory: What are the implications of the spin-off from the parent company?

Roopa Kudva: For one, all decision-making authority has now devolved to India, which means that our investments committees are all India-based, and we take all other decisions related to the organisation in terms of key hiring, where we want to have our offices, etc. in India.

More importantly, we have autonomy and are now able to look at some additional areas of work that were not a part of our global strategy but are unique to, and very important for, India. Take the judiciary: can we get entrepreneurs to come in and help make our judicial system more citizen-centric? Or it could be by ways to use judicial data, and even simple things like solutions that enable citizens to know what time their cases are coming up for hearing instead of having to go and wait 10 hours at the courthouse.

Then there are areas like agritech and public digital platforms (digital infrastructure which is created as a public good), which can then be used to deliver government services more effectively, or which can help entrepreneurs come and build businesses on top of that – like the Aadhaar and the India Stack.

Autonomy has also changed the way we evaluate ourselves and hold ourselves accountable for performance.

There is the whole question of financial returns, of course – that doesn’t change whether you are global or autonomous. But this changes the way we look at social impact. For example, since (Omidyar Network) India has become autonomous, for the first time I'm tracking the fact that these (efforts) put together have impacted 300 million individuals. Or we have companies that have brought in innovative business models to India, whether it is a Pratilipi, an Affordplan or a DailyHunt, or a Bounce, or Vedantu, or Toffee, which is trying to sell insurance like an FMCG product.

These are all innovative business models that have come to India for the first time, and are an important part of impact.

These are the three things that have changed because we’ve become autonomous: decision-making, spreading our work to additional areas vital to India, and the way we measure the impact we create.

YS: So, how do you measure the impact created? Is it lives impacted?

RK: There are three metrics. One is lives affected, which is the easiest one – we have positively impacted 300 million lives.

The second is the depth of impact. We may have impacted 300 million lives, but if we are, say, a Transerve, which used drones for land-mapping and enabled the Government of Odisha to provide land titles to 250,000 slum families (one million people), the depth of impact on the lives of those individuals was phenomenal, much more than, say, a DailyHunt, which is definitely touching my life but not deeply impacting it as much as the previous example.

The third metric is the impact that our investees are making to the system – it could be innovative business models, how they are influencing policy and scores around the sector. For example, when we give out grants, which is 25 percent of our total investments, for something like the Digital Identity Research Institute, which is producing research on Aadhaar for the first time, it is creating systemic impact. So new business models, research in under-served areas, these are all examples of sector-level impact.

As we are funded by philanthropic capital, we have the luxury of being more patient. And sometimes you need that additional patience to really build a big business, because some things just take time. However, having said that, financial success is important to us.

We have a model of sector change - one that combines for-profit investing and non-profit grants, which is unusual. At the end of the day if we can do that, it can help build larger, sustainable companies, and support impact investing. So I think we are strongly focused on exist and on financials success as well.

YS: How do you filter who deserves what?

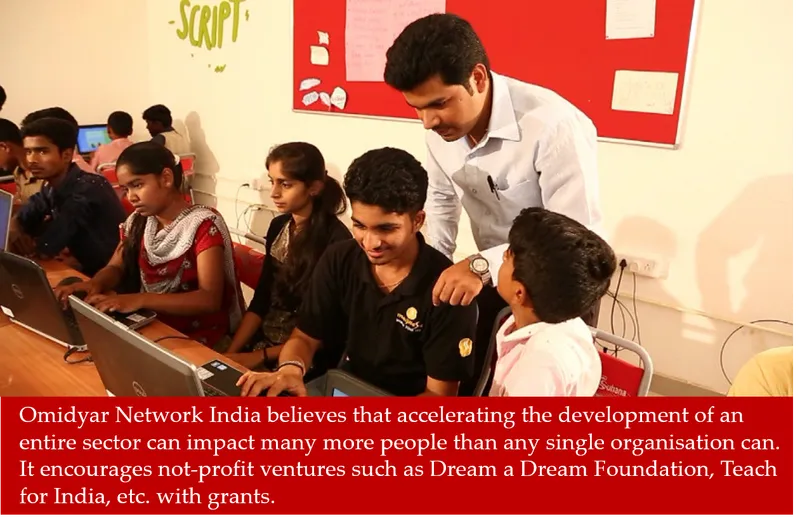

RK: We believe that accelerating the development of an entire sector can affect many more people or impact many more people than any one single company or one single organisation. But if you want to bring sector-wide change, then you need three kinds of entrepreneurs.

One, you need a Pratilipi, Bounce, Daily Hunt or Vedantu, who are the for-profit market innovators who bring about disruptive innovation in that sector. You need those market innovators.

But you also need sector-level infrastructure. In education, for example, teachers play a very important role. That's why you need a Shaheen (Mistri) in Teach for India, who's creating that market infrastructure, or something like The Microfinance Exchange, which provides forex cover for microfinance companies for forex borrowing. That is where you need the non-profit entrepreneur.

The third thing you need is policy that is supportive of entrepreneurs who create an ecosystem where such ventures can flourish. That’s where you need the public sector or a bureaucrat who is entrepreneurial.

I would say that all three have to come together if we want sector change.

For each of the six sectors that we work in, we’ve published our investment strategy as to what within that sector we will invest in. We are quite disciplined about that.

YS: There are quite a few public schemes that have also sought to create social impact – the Ujjwala LPG connection scheme, Ayushman Bharat, Swachh Bharat, etc. How has the private sector – entrepreneurs and others – leveraged this?

RK: It’s great that we have toilets and subsidsed LPG connections, all of which was very vital for India. But today, a young and aspiring India wants to see even more rapid change. Today, with your mobile phone and low data costs, you have a window to what is happening everywhere in the world, no matter how educated, or rich or how poor you are. That access has raised the aspiration levels of everyone across the country.

We are seeing that technology, and more importantly the mobile phone, has become the biggest driver of social impact in India. So entrepreneurs come in and leverage the mobile phone and technology to provide a range of aspirational services, whether it's access to financial services, education, jobs, transportation, healthcare, social interactions - all of that can be done for the middle-income and lower-middle-income populations via the mobile phone.

We need entrepreneurs who are building solid, tech-based businesses that can scale up rapidly and provide affordable aspirational services to this population. Jan Dhan, or the fact that you now have 400 million people in India with access to the internet, or that data usage in India is now comparable with the most advanced countries in the world, that 30 percent of India has smartphones…all of that means that entrepreneurs have an opportunity to build large businesses that provide these aspirational services at an affordable cost. And those are the entrepreneurs we are investing in.

YS: This sounds like a great setting, but there are challenges and obstacles too. How do we overcome those?

RK: Some things we need to be realistic about. One, while the opportunities are huge, India is a complex country - we have a large population with a huge diversity in income levels, social and cultural contexts, education levels, etc. Business models have to account for the uniqueness of India.

The second reason is that at the end of the day, compared to China or the US, where you have had entrepreneurs building large businesses, GDP per capita in India is much lower. So, building larger businesses is going to be a longer haul.

And yet, we have seen the change: compared to a year ago when we had half the number of Unicorns we have today. Ten years down the line, that number will increase. But we have to acknowledge that the pace in India will be slower because of the affordability factor.

For entrepreneurs, it means that they will need to be relevant to the local context (and not that of a US or China) The Indian context is that the next half a billion people who are going to come on to the Internet do not know English. So local language becomes important in building your business model.

The Internet is very intimidating for women and very hostile to women. They may have a smart phone but in the smaller cities and towns and villages, it has been drilled into them that mobile phone exposes you to “bad influences”. How do you get more women to come online and design your own business that is more women-friendly?

How do you build trust among consumers conducting business online? If your mobile connection goes off in the middle of a transaction, people feel that they've lost their money. So how do you build trust? The complexity comes not just because of GDP per capita being lower, it also comes because you have to build business what take into account the reality of India.

At ONI, we are very happy to see a lot of the entrepreneurs who we are funding are actually coming from the smaller towns, which is a great thing because they understand these issues intuitively than someone would has been brought up in a large city, and went to the top schools in the country. I think that the real people who are going to drive the big change in the entrepreneurship for the mass market are going to be the new entrepreneurs from the smaller towns.

YS: Tell us more about what Omidyar is doing to make digital benefits accessible to more people using local language technologies, or voice-driven solutions – leveraging tech for impact investment.

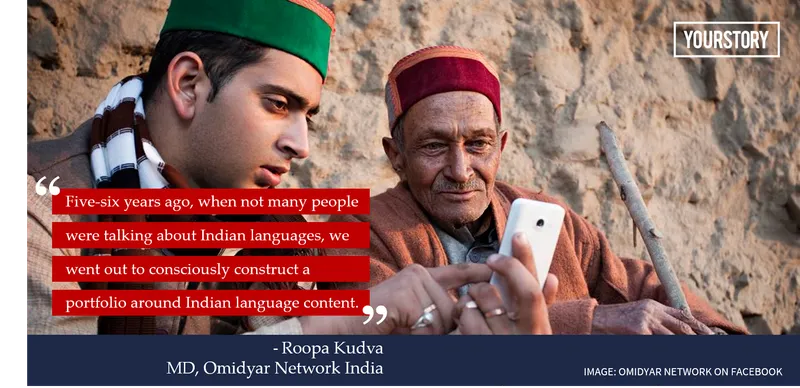

RK: We were among the early investors to recognise the value of Indian languages in truly leveraging tech for impact. Our investment strategy is a technology for impact-led investment strategy. One of our first investments was in a company called Indus OS, which makes an Indian language smartphone operating system, where you can have your screen in one of 13-14 Indian languages. Our second one was Daily Hunt, which aggregates news content in Indian languages. The third one is Pratilipi, which enables self-publishing in Indian languages; 70 percent of their customers are women, which is very encouraging. Women are coming online, reading, writing their stories, becoming authors – it makes them comfortable doing all that online.

The fourth is called MyUpchaar; think of it as a WebMD in Hindi. We've been consciously seeking such businesses. Five-six years ago, when not many people were talking about Indian languages, we went out to consciously construct a portfolio around Indian language content.

We have six or seven really interesting organizations around the credit theme. There are five organisations which provide credit to small businesses. We believe that this is vital for improving SME productivity and improving income inequality in India – Vistaar (lending for rural SMEs), NeoGrowth (lender to urban SMEs), Varthana (lends to affordable private schools), Intellegrow (lender to small businesses) and Zestmoney (online B2C lender).

This powerful portfolio around credit, both offline credit and as well as digital credit, is another distinguishing feature of our portfolio.

And the third cluster I will point out is in education – whether it is Vedantu, or Doubtnut, or Aspiring Minds, they are all using technology to solve different problems in education and skilling. Doubtnut is an app. If you're a kid studying maths and you get stuck anywhere, you can just take a photo of where you’ve got stuck, from wherever, and upload it, and in no time you get back a video, explaining a solution to you in Hinglish.

What is common across the portfolio is the target segment – the lower and middle-income segment who we call the next half billion – being helped by tech-led business models.

I should point out our philosophy about tech is slightly different. While we believe that technology is a great force for good and can drive social impact at scale in a manner that could not be done before. This can only be done if it is part of a larger social contract.

Countries need to recognise that technology can cause great harm as well. Therefore we are big believers in the need to promote privacy, data security, and user control. Consumers must have recourse to harm caused by technology.

We have made significant investments in organisations that do research on privacy. One is a privacy network comprising all the leading think-tanks in India (who are coming together) to work on extensively on privacy. They are conducting privacy and data clinics for startups so that even before the regulations come in, they recognise how following good data practices and protecting consumer data can actually be good for the business.

YS: Omidyar has defined something called a Good ID. Tell us more about that. Is India part of that?

RK: Oh yes, it is. In fact, it is a very big part of our work in India under which we are conducting these privacy clinics for startups, and under which have funded a Digital Identity Research Institute. Our digital identity is the biggest identity we have today – be it Facebook or Aadhaar. We are saying a Good ID must follow four-five key principles.

One, it should be accessible and inclusive to everyone. Two, there should be privacy. Three, there should be user control. So even though I don’t own my data and somebody else owns the data, I – as the owner of the digital identify - should be able to control who uses my data and for what. And four, it should provide me with recourse in case of harm. If for any reason there has been a data breach or someone has used my data to cause me harm in some way, the system must provide me recourse to be compensated adequately or to get justice.

These are the principles that we believe in and are funding research on.

YS: There has been a lot of talk about the next half billion. The question again is one of affordability. Will they pay and if they do, how much are they willing to pay?

RK: I think we are already beginning to see shifts happening. So far, investor-investee conversations in the boardroom were all about scaling up rapidly. How do you acquire customers as quickly as possible? And how do you keep your customers engaged? Customer acquisition and customer engagement were the most important metrics.

Today, conversations have started shifting and there's much more emphasis on cost of customer acquisition. How do you bring that down? There's a lot more emphasis on monetisation and new monetisation models… Investors and entrepreneurs are both becoming more conscious about this. Having said that, we again have to recognise that the context of India is different. I think of entrepreneurs who can design for what I call “extreme affordability” is going to be important.

I think people who succeed will be those who one, are able to provide extreme affordability, and two, those who are genuinely providing huge value to the customer.

Railyatri is a good example of such monetisation. They started off as a content platform providing information to rail travellers on questions like what is the probability of my tickets getting confirmed, etc. Today they have different revenue sources, including sales of train tickets, bus tickets, deals with large corporates, advertisers, and brand partners who want to advertise to train travelers.

YS: Jobs and employability are the other big challenges. Which area requires the most intervention in India today?

RK: Education and skilling is massive. But given our demographics today, the immediate issue is that 1 million people are entering the working age population every single month. So India has to create 12 million jobs a year for the next several years. That's a massive number.

We are doing two things there. We have invested in Aspiring Minds, which helps employers assess skills. We have also invested in a company called iMerit, which takes people from very underprivileged backgrounds and puts them to work with global companies in areas like AI, etc.

But the bigger work that we are doing in skills is on the non-profit side. We are trying to see how closely we can work in terms of developing public digital infrastructure for skills. We are engaging quite closely with the government too. How do you do skill development for MSMEs? They are the biggest creator of jobs.

How do you create a technology stack whereby you can make skilling much easier so people can understand more easily? Who is a reputed skilling institute? Where are the jobs available? What kind of skills are really needed in the market today? The kinds of tools needed to create a technology stack? Our interventions in the skilling space are a lot about supporting government policy initiatives in skill development.

YS: How has your personal evolution been – from a financial services sector CEO to the social impact sector?

RK: It’s very different, and yet there are a few things that I can draw on from my past life. When I was with Crisil, I worked with entrepreneurs who had arrived. From there I moved to Omidyar Network, where I work with entrepreneurs who are just starting their journey. It's very different but also very inspiring.

The most exciting and inspiring part of the transition to this new role is the fact that I work with youngsters today whose aspiration and ambition levels are very high and whose families are encouraging them to become entrepreneurs. They know no fear, there's no fear of failure.

The best minds are going into entrepreneurship. Money is available for them. It’s a really exciting space to be in.

What I really leverage from my past role is knowledge of a really wide range of sectors. And also the knowledge of working with entrepreneurs – who has the potential to make a good entrepreneur? The third thing is that our startups have great ideas and passion, which are great to get them off the ground, but you need to support a startup. Building up a business which means managing and building systems and processes, thinking about your cost structure, driving continuous improvement that can squeeze that extra bit of revenue…Over the last four years in India, we’ve built a phenomenal team – one of the best investment teams in the country, they’re also very passionate about making a difference.

It’s been very different, but it's been great fun.

YS: What’s the one thing that you're really looking forward to seeing over the next three years or so?

RK: I feel that India’s time is now. The ecosystem for entrepreneurship and has never been better. We have outstanding talent becoming entrepreneurs, and we have a lot of money going into entrepreneurship. We have a generally supportive policy environment, and we have a ready market. Along with smartphone penetration and data costs, you have the massive aspirations of the people.

This is why we are excited about having become an autonomous entity. I’m looking forward to seeing these entrepreneurs grow and thrive and succeed. Because if they do so, I think they will benefit the next half billion. Finally, I think if the income levels in India of the next half billion can grow faster than the income levels for India as a whole then I can say that we have been truly successful.