40 years of technology innovation - what we can learn from the dawn of the Digital Age

This book provides a sweeping overview of 50 innovations across four decades. It shines the light on their rise and fall, and the ecosystems of linkages necessary for success.

Launched in 2012, YourStory's Book Review section features over 250 titles on creativity, innovation, entrepreneurship, and digital transformation. See also our related columns The Turning Point, Techie Tuesdays, and Storybites.

UK business journalist Ian Wallis has put together a book spanning key innovations of the computer age, titled The World’s Best Business Ideas. The book was originally titled 50 Best Business Ideas of the Last 50 Years; most of the innovations are technical while a few are business process ideas.

I have summarised my key takeaways from the book in the sections below, and in Table 1. See also my reviews of the related books Quirky, Fifty Things that Made the Modern Economy, Frugal Innovation, The Creative Curve, and Iconic Brands.

The material is spread across 275 pages and makes for an informative read. The references (and font) could do with considerable improvement, though – and the title comes across as a bit exaggerated. The introductory (or a concluding) chapter could have done a much better job of analysing the broader implications of the successes of the profiled innovations, and why some of them eventually faded away.

The book claims to profile key innovations of five decades, but the section on the fifth-decade profiles only two innovations (e-readers, Google’s 80-20 innovation rule). Perhaps the author and his team of writers ran out of steam, interest or funding?

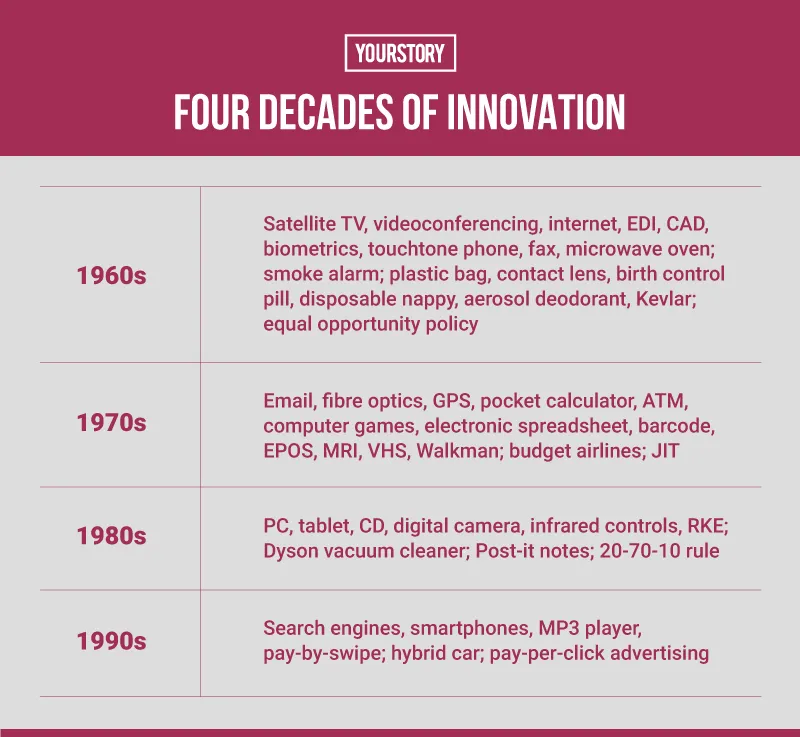

Four decades of innovations

The innovations are variously described as transformative (PC, internet), controversial (contraceptive pill, plastic bags), and outmoded (fax machine, pocket calculator). Innovations differ also in terms of focus and impact, e.g. security (biometrics), entertainment (games), business efficiency (spreadsheet, barcode), and consumer friendliness (e.g. e-readers, ring pull).

The journey of innovation is not always linear and smooth. It involves multiple players involved in “tweaking, deconstructing, and reconstructing” the original product. Some innovations arose out of serendipity, e.g. Post-Its, Kevlar, smoke alarms, microwave oven.

Interestingly, many innovators were laughed at when initially proposed, especially by experts in the field, e.g. fibre optics, VHS, Dyson cleaner. Some innovations are the result more of business model than differentiating technology. The rise of budget airlines is a good example, pioneered by Southwest Airlines.

Knowledge from one field can sometimes hop over into new domains as well. The microwave oven for the kitchen market built on electrical energy and radiation research during World War II. Other innovations were added to address concerns like patchy cooking, e.g. rotating tables inside.

Solving an immediate problem

Some innovators came up with their solutions out of a need to solve their own immediate problems, e.g. the ring-pull or pull-tab on drink cans. Ermal Fraze got this idea when he wanted to open a beer can during a picnic, but realised he had forgotten his can opener. His invention is now used in cans for soda, pet food, soup, oil, and even tennis balls.

Music lover and scientist James Russell was frustrated with the scratching and warping of vinyl records, and patented contact-less optical recording and playback via CDs in 1970. Sony’s marketing line for CD players was ‘Perfect Sound Forever.’ The first album to be recorded for CD was Visitors by ABBA in 1981.

The idea of cash machines (forerunner of the ATM) came to John Shepherd-Barron when he was unable to get cash outside of banking hours. “The ATM is not just a cash dispenser; it’s a serious money maker,” the authors explain, referring to additional services like screen ads and related payment services.

James Dyson was frustrated with the clogging of vacuum cleaner bags. He invented the bagless model based on cyclone technology. Making the dust chamber transparent helped increase consumer trust as well.

Timing

Some innovations take a whole ecosystem of players to fall in place, which takes time and a lot of orchestration. Consumer education and market acceptance are key factors here, as seen in the long journey of videoconferencing tools.

The AT&T PicturePhone was first introduced in 1964. It took a while for costs to fall enough till businesses accepted it. A number of players added innovations like data communication via the internet.

Business processes

The book also touches on process innovations and not just products. Examples include Google’s “20 percent innovation time” for employees on related side projects, and Toyota’s Just in Time (JIT) inventory management.

Another example is GE’s 20-70-10 rule for company performance. The top 20 percent of exceptional employees should be rewarded, the middle 70 should get training, and the ineffective 10 should be fired.

To ensure a culture of “creative chaos,” Google required employees to spend 70 percent of their time on core work, 20 on related projects, and 10 on new projects. An in-house incubator was also added later. Successful innovations, as a result, include Google News, Gmail, Google Sky, Google Art, and AdSense.

The role of government

Some innovations required significant government (and even military) funding to get started, e.g. ARPANET, one of the internet’s precursors. GPS also had its roots in US military technology for monitoring vehicular movements.

Government interventions like equal opportunity policies play an important role in areas ranging from payscales to anti-discrimination laws. Government moves in deregulation and privatisation have shaped the transformation of industries ranging from airlines to telecom, spurring new waves of innovation.

Competitive forces

The video, gaming, PC and smartphone industries are good examples of the importance of competitive strategy to capture market share of innovations. “The launch of the desktop computer is, arguably, the most important business development of the last 50 years,” the authors explain.

A range of players jockeyed for top position with differing business models, licensing, and integration strategies. Mobiles have since taken over as the principal personal device. An Apple intern called Marc Benioff came up with the idea of the App Store (he later went on to become CEO of SalesForce.com).

In the gaming sector, home gaming eventually beat out game arcades. Mobiles, in turn, have spurred a new wave of ‘casual gaming’.

The Betamax-VHS battle pitted Sony against JVC, which eventually won due to speed and better ecosystem partnerships. But videotapes eventually lost out to VCDs and DVDs, which in turn faced a formidable competitor in streaming.

Lycos, Yahoo and Infoseek were the dominant search engine players until Google came on the scene. PageRank and AdWords helped Google dominate the market, but other players like Bing, Baidu, and Yandex have joined the fray.

Cascading effects

Many innovations, such as the PC and internet, have had cascading effects across industries. The lesser-known device in this category is the infra-red remote control for TV, invented by Canada’s Paul Hrivnak in 1980. It would spawn memorable terms like ‘couch potato’ and ‘channel surfing’.

To prevent people from switching channels instantly, content programming was redefined to have action sequences right in the beginning, and include credits with the end of the programme (and not after). MTV rode the wave well, and launched the Beavis and Butthead show along with the music video.

Some innovation had broad social impact which upended traditional roles and biases, eg. the contraceptive pill. It gave women power over planning motherhood, and expanded their career options.

Unintended side-effects and spillovers

Some innovations had features which ballooned into catastrophic impacts after large-scale use, eg. plastic bags, disposable diapers. New innovations are springing up to address these issues, eg. bio-degradable products, recycling services.

The plastic shopping bag that is so much in use today was invented by Sweden’s Sten Gustaf Thulin in 1965. Changes in consumer attitudes, not just government regulation, are needed to reduce the proliferation of plastic waste.

Aerosol deodorants enjoyed a brief market boom before CFCs were banned ingredients. This was due to their environmental damage. Replacement propellants were found.

New waves of disruption

Key challenges to many companies come not from competitors but from new categories of technology. The fax machine and the pocket calculator had their heyday in the 1970s and 1980s, before being displaced by email and mobile phones, respectively.

Digital music and portable MP3 players led many record shops and chains to close down. Email and digital messaging have seriously impacted ‘snail mail.’ A challenge to satellite TV is fibre-optic television.

“The greatest threat to the soft contact lens industry is the availability of laser surgery,” the authors explain. This disruption depends on affordability and perceptions of safety.

CAD technology, first developed by Ivan Sutherland, was initially popular in the 1960s on large computers. But workstations and PCs later introduced new players who became dominant; Autodesk was founded in 1982.

Tampering

Not all users of tech innovations are benevolent. The authors document how many products can be "hacked" by unscrupulous characters.

Examples include fingerprint scanners, which can be “hacked” by “fake fingers”. Multi-test systems will be needed in such cases; this “cat and mouse” or “cops and robbers” scenario is played out in the case of many innovations.

B2C and B2B

While B2C innovations understandably hog much of the media limelight, the authors document a number of B2B innovations as well, e.g. EDI. Some devices like the early digital camera were expensive, and sold first to media organisations and professional photographers.

Products like Sony’s CyberShot opened up the mass market for digital cameras. Digital cameras led to the demise of film-processing studios, but smartphones, in turn, are eating into their market share.

Interestingly, incumbent mindsets may come in the way of accepting new innovation. “The entrenched professional will always resist innovation much longer than the private customer,” the authors explain.

Appealing to the individual customer worked well for brands like Apple. “Steve Jobs had constructed a compelling persona which mimicked that of the friendly guy at the internet café, rather than the CEO of a global conglomerate,” the authors write.

Standards and legal issues

The authors document how many innovation categories really took off only after standardisation emerged. But this process can also create winners and losers unless all players align their agendas.

Examples include the rise of standards for EDI by the National Standards Institute and the UN, and common standards for the fax machine. Android was developed by the Open Handset Alliance, a consortium of firms promoting open standards for mobile devices. The MP3 standard was developed in Germany by Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft.

The innovation landscape involves multiple players – even competitors, and the rivalry can turn ugly, e.g. lawsuits over who invented MRI, Walkman. Terms of the settlement over royalties and payments did not always work in favour of the original inventor in many cases.

The importance of design

Design coupled with technology can popularise innovations even faster. The cumbersome rotary phone was eventually replaced by the superior and easier-to-use push-button and touch-tone phones.

Tonal touch also led to new services like IVR and telephone banking. The cordless landline phone also paved the way for the acceptance of mobile phones. Colours of products became part of their defining feature as well, as seen in the ‘canary yellow’ of Post Its.

Inclusive design has also brought in experience elements for users who differ along lines of gender, physical ability, and orientation. “The road to equality remains a long and rocky one,” the authors caution.

International players

While much of the book addresses innovations by US and European firms, there is also notable mention of Japan and South Korea. Hong Kong was a pioneer in micro-payment using swipe cards like Octopus, while South Korea had UPass and UK rolled out Oyster.

“Moscow Metro became the first transport network in Europe to start using swipe card technology, in 1998” the authors observe. Other US cities then followed. Malaysia’s smart card initiative is called MyKad.

Print books versus e-readers

The book ends with the story of e-reader technology, based on electronic ink. “But we should not underestimate the incredible durability of the traditional book. Worldwide, the paper book still dominates, and has done so in more or less the same form since the invention of the printing press in the year 1440,” the authors explain.

“It never runs out of battery life, and it provides a tangible sense of ownership that e-readers will never quite replicate,” they add. “What is clear though, is that the e-reader revolution is only just beginning,” the authors sign off.

Edited by Saheli Sen Gupta