From mindset to skillsets: six steps to creativity for innovation

This must-read book by two bestselling authors provides an actionable framework and useful tips for increasing your creativity quotient.

Launched in 2012, YourStory's Book Review section features over 250 titles on creativity, innovation, entrepreneurship, and digital transformation. See also our related columns The Turning Point, Techie Tuesdays, and Storybites.

A wealth of tips, examples, and worksheets on individual and group creativity is featured in the compelling book, The Creative Mindset: Mastering the Six Skills that Empower Innovation, by Jeff DeGraff and Staney DeGraff.

One chapter focuses on each skill, and provides worksheets and case profiles for readers. It would have been great to mention actual names of some of the companies and professionals profiled in the chapters.

Jeff DeGraff is a professor at University of Michigan’s business school, and advisor to companies like Google, GE and Mercedes-Benz. Co-author Staney DeGraff is CEO of Innovatrium, an innovation consultancy. Their earlier book is The Innovation Code: The Creative Power of Constructive Conflict (see my book review and author interview).

Creativity is not just a mindset but a skillset and craft, the authors begin. It applies to everyday practical activities, and not just to occasional big-bang projects. Creativity is an ongoing process, and many creative works are never fully “completed,” as seen in multiple editions and sequels of books, movies and software.

Here are my key takeaways from this valuable 210-page book, summarised as well in Table 1. See also my reviews of the related books How to Steal Fire, The Art of Noticing, Quirky, How to get to Creative Ideas, The Creative Curve, and The Art of Creative Thinking.

The creative mindset

Many large and small success stories of today started off with simple and cumulative creative sparks. Examples include Starbucks, which was inspired by Italian cafes and then expanded from commodity product (coffee beans) to upscale product (cappuccino) and even theatre experience (modern coffee houses).

Creative people can see what others overlook, challenge professional boundaries, and overturn business assumptions, the authors explain. “Creativity is the power that generates innovation,” the authors write.

Creative people have the motivation, passion, and drive to change things. They have the “will and skill” to make innovation happen, and see possibilities where others see dead ends.

Ordinary people can make things extraordinary through creativity. Examples range from party costumes to serial entrepreneurs, from hustling with barters when broke to neighbourhood ‘fixers’ who repair and refurbish things.

The authors describe the creative mindset as a frame of mind where you are aware of your most creative times and places, capture ideas effectively, dig deeper to question assumptions, look for anomalies, and have faith in your capabilities.

“The creative mindset is something you can develop and cultivate, and it requires constant practice to achieve a mastery of craft,” the authors advise. They draw on the work of creativity researchers like Paul Torrance, Max Wertheimer, Karl Weick, Arthur Koestler, Alex Osborn, Edward de Bono, and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi.

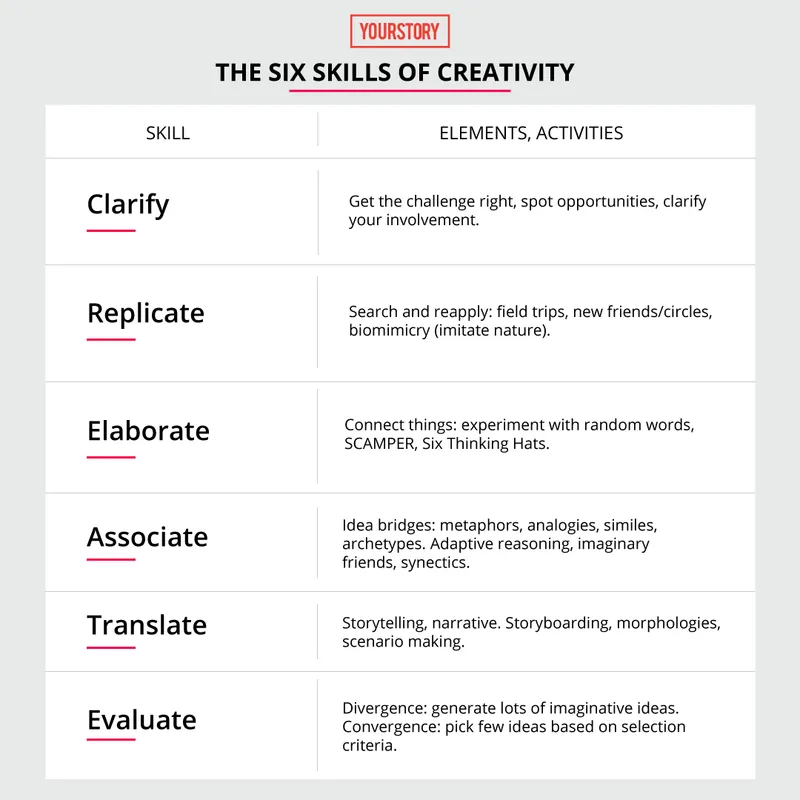

Innovation in organisations is the result of creativity of individuals and communities. The authors’ skill framework is based on the apt acronym CREATE – Clarify, Replicate, Elaborate, Associate, Translate, and Evaluate.

“Using the six skills, you can apply little acts of imagination to the challenges of the day,” the authors emphasise. Creativity is not just about genius, magic, innate gifts, or even the divine hand.

1. Clarify

Creative people are not just problem solvers but problem spotters. They can identify, investigate and articulate problems and patterns, the authors explain. They draw insights through observations and conversations.

Creativity begins with spotting opportunities for unmet needs, inefficiencies and complexities. Examples of solutions include food trucks, parking apps, and student counseling services.

Commitment to solving a challenge involves understanding one’s motivation, expected impacts and benefits, and mapping of knowledge needs and execution roles. Learning from others is important, via active listening, open ended questions, and meaningful conversations.

2. Replicate

Replication involves taking an idea from one area and applying it to another. “Creativity is just connecting things,” in the words of Steve Jobs. However, there is a strong element of pattern recognition and sensemaking involved, beyond just copying.

Examples include the Mayo Clinic check-in experience inspired by the Ritz-Carlton, early manufacturing of Hershey chocolate bars using machines modified from soap production machines (seen at an 1893 expo), and Johannes Gutenberg’s printing press design based on wine presses.

Idea logs can be used to record “search and apply” insights from field trips and walkabouts. Change of stimuli and physical activity can spur creative thinking. Trips need not be to exotic places but even unexplored neighbourhoods.

Expanding diversity of social circles and activities helps go beyond dominant worldviews. “Creativity is as much about the quality of our connections as it is about the uniqueness of our ideas,” the authors explain.

Examples include “pracademics” who combine practitioner and academic perspectives, and work through a portfolio of diverse projects rather than a single job. Albert Einstein had a diverse range of collaborators, including engineers and explorers.

Observing and mimicking structure, function and processes in nature is another source of creativity. Examples include Buckminster Fuller’s model of a spaceship based on a pollen spore; rudders designed like whale flukes; and fluid workspaces designed like aquariums.

Superglue is used for closing wounds as well. Highway repair techniques include the combination of cement with industrial canvas.

3. Elaborate

Elaboration involves connecting a familiar idea with a new unfamiliar one, to create a novel hybrid. It can be an individual or group activity, with a safe space for free-flowing ideas through brainstorming.

Making faster and better connections can convert seemingly trash ideas to treasure, the authors describe. It involves going beyond one’s worldview, and getting used to the “uncomfortable, unexpected and uncertain”.

Connecting existing objects or ideas to random words (written or spoken), can force unusual combinations and modifications to emerge. Such connections can emerge spontaneously, or through explicit rigorous activity.

Alex Osborn’s SCAMPER acronym lists methods like Substitute, Combine, Adapt, Modify/Magnify, Put to other uses, Eliminate/Minimise, and Reverse/Rearrange. Another useful tool is Edward de Bono’s Six Thinking Hats (information, emotion, critic, possibility, alternatives, process).

Examples include the spork (spoon combined with fork), fans combined with lights, and pocket zippers that go from bottom to top (thus preventing objects from falling).

4. Associate

The “wildly generative and delightfully unexpected” power of association involves going beyond idea linkages to idea bridges. It is more than “connecting the dots,” the authors explain.

Sometimes, people are too close or too far from a problem to spot a solution. The point of view of the person itself needs to change in this case, the authors write.

Association methods include adaptive reasoning (eg. analogies, metaphors) and empathy maps. Imaginary friends involves ‘role-storming,’ eg. visualising what would be done in this situation by Steve Jobs or your wise grandmother.

Synectics is a group creativity technique developed by consultants George Prince and William Gordon, based on root cause analysis, metaphorical excursions, and force-fitting. After generative phases of ‘stretch’ and ‘simmer,’ a sense of judgment based on objectives selects the final approach.

Examples include gamification, modeling a sports coaching agency like a music school (with auditions and specialisation), or designing a healthcare centre like a spa.

5. Translate

Successful innovators conjure ideas but also translate the vision into compelling stories that inspire, attract and unify others, the authors explain. “Given the endless combinations of characters and plot elements, storytelling is a surprisingly simple method of generating creative possibilities,” they write.

It takes practice and skill to be able to tell a story in a coherent, meaningful and compelling manner. “Our ability to tell stories may be among our most potent creative skills,” the authors emphasise.

“The ability to see ourselves as different people in different settings is one of the most powerful kinds of creativity we can have,” the authors explain. Effective narratives can bring together diverse stakeholders. Stories help make sense of the world and also change it.

Examples include Mahatma Gandhi’s narrative for India’s freedom movement; the use of science fiction in consumer electronics and even military tactics; and the adventure story behind the Dos Equis beer brand.

Storyboards help create a vision of how things intertwine and progress in sequence. Multiple stakeholders should participate in telling and re-telling the stories, the authors advise. Morphologies are detailed taxonomies of object features and attributes, and can be used to design products as well as movie plots.

Scenarios describe best and worst case outcomes, and some clustered states in between. Wild card factors can shift the likelihood of these scenarios, the authors caution. Examples include changes in regulation, disruptive technology, or a crisis.

6. Evaluate

The evaluation process of proposed ideas is both an art and a science, the authors write. Divergence can be used to create imaginative ideas, but convergent criteria will be needed to select the final ones: cost, time, feasibility, acceptability and usefulness.

Based on a 2x2 matrix of implementation effort and payoff, the GE Work-out Evaluation Grid categorises ideas as big wins, small wins, special cases, and time wasters. Care should be taken to weigh positives, negatives and interesting features of each idea combination.

In sum, the six skills yield different results for different people, depending on their journey and context. People should find their most creative times, and ways of staying in that state, eg. through walks or breaks.

“Find your flow state,” the authors sign off.

![[The Turning Point] How lack of awareness about the solar market led these brothers to start Loom Solar](https://images.yourstory.com/cs/2/79900dd0d91311e8a16045a90309d734/turningpoint2-1601622989968.png?fm=png&auto=format&h=100&w=100&crop=entropy&fit=crop)

![[The Turning Point] How a personal pain point influenced the founding of edtech startup Springboard](https://images.yourstory.com/cs/2/79900dd0d91311e8a16045a90309d734/turning-point1-1599224818959.png?fm=png&auto=format&h=100&w=100&crop=entropy&fit=crop)