How community support and the will of its staff helped Mitti Café pivot during the pandemic

In 2017, Alina Alam started Mitti Café, that employs and trains adults with physical and intellectual disabilities. When its cafes shut during the pandemic, it pivoted to cafes in hospitals and other public spaces, provided four million meals to the needy and started a gifting initiative.

In 2017, 24-year-old Alina Alam started the chain from Hubballi, Karnataka, completely run and managed by people with physical and intellectual disabilities.

The concept of Mitti Café came to Alina during an internship with the Samarthanam Trust for the Disabled in Bengaluru.

A Mitti Cafe

In an earlier interview with YourStory, she had said, “I always wanted to build a social enterprise that engages these people in an empowered setup, outside the scope of charity. And that’s how I envisaged the concept of Mitti café.”

Before the pandemic struck, there were 13 cafes, all within corporate campuses in Bengaluru. These went into hibernation, causing a loss of livelihood to both its employees and trainees.

Alina remembers receiving calls from all her employees sitting at home–they wanted to earn with dignity. The cafés had no cash surplus at hand, was started with zero capital, and initially ran solely on grants, contributions from the community, and with support from IIM-Bangalore’s incubator, NSRCEL.

“When Covid hit, we had over 250 people with disabilities who were directly engaged with Mitti. The community came forward along with individuals who donated, so we could at least look at survival,” Alina tells HerStory.

Meals for the hungry

Hemant, an employee of Mitti Café afflicted with cerebral palsy and autism, came forward with an idea that led to its first pivot.

“There were people for whom we had provided accommodation. They were going hungry, and Hemant’s words were, hum log khaana bana sakte hai. His vision was if we started cooking, no one will stay hungry. With the support of NSRCEL who connected us with a few professors in IIM-Bangalore, we raised the initial funds for the meals,” Alina says.

Mitti Café’s team of adults with disabilities have so far cooked, packed, and served over four million meals to the economically vulnerable under its flagship programme, Karuna Meals. Beyond the Covid period, the team has also cooked meals during the Mangalore floods and served them to orphanages.

“For every Rs 25 we raised for a meal, Rs 8 went towards the labour cost, for the team of disabled cooking it. We managed to help our team continue to earn their livelihoods in this way,” she adds.

During the pandemic, the café also found another way to generate income. It started another vertical, Mitti Good Gifts, in association with its partner NGOs–gifts made by people with disabilities, acid attack survivors, tribal women, and others procured mostly by B2Bclients.

This sense of purpose drove the team together and they opened cafes in locations that had fewer restrictions or more likelihood of customer footfall–hospitals, railway stations, airports, residential societies, and colleges.

The power of community support

Infosys founder NR Narayana Murthy with Alina and staff at a Mitti Cafe

Today, there are 23 Mitti cafes across four cities--Bengaluru, Kolkata, Hubballi, and Delhi. There are plans to expand this concept to Chennai and Hyderabad in the future. The two standalone cafes are located in Banashankari and Yeswanthpur in Bengaluru.

And, to think, it all began from a dilapidated shed overrun by rats that students helped clean and fashion into a café in Hubballi five years ago.

“In the early days, I faced multiple rejections, but the community came forward to help. I went door to door, and from shop to shop asking people to contribute to the cause in kind. Absolute strangers came forward to donate stuff–from spoons, to a second-hand oven to a fridge,” Alina recalls.

It works on a simple model–a minimum of 80 sq. ft of space to start a café that would employ eight to 13 people with disabilities. It has a curated menu that is easy for the team to prepare.

Mitti is famous for its Kulhad chai, with the kulhads (clay cups) coming from a facility in Sunderbans managed by people with disabilities. Alina believes in making the supply chain as inclusive as possible.

Mitti Café has been able to train over 2,500 people with disabilities. Their lives have changed, for the better.

Alina talks of Lakshmi, a single mother and the only earning member in her family, who is speech and hearing impaired. She works hard so that her children will have a good education and take her on a world tour.

Heart-warming impact

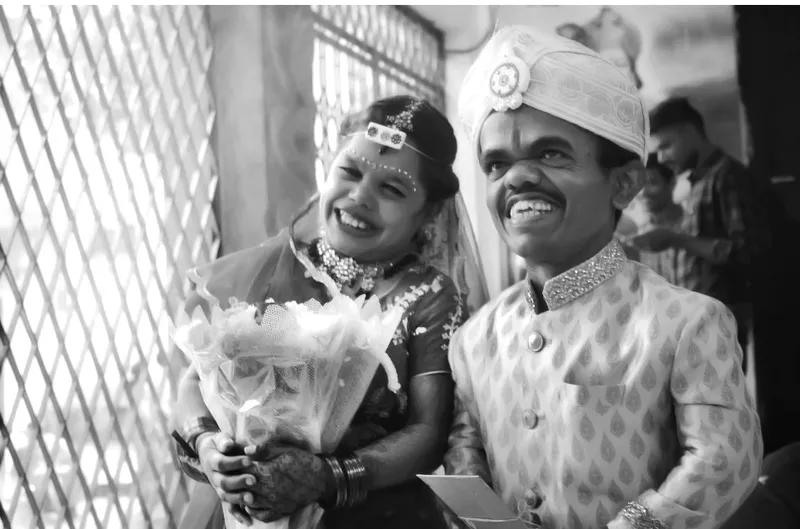

Roopa and Bhairappa at their wedding

And then, there are the love stories.

“Bhairappa suffers from dwarfism, motor disability, and intellectual disability, and had been rejected from 80+ jobs when he came to Mitti. He came in barefoot, and now, he’s the training lead. He met Roopa at the Wipro café while he was working at the Infosys Café and got married during the pandemic. Theirs is a Wipro-Infosys love story,” shares Alina.

Right now, the focus is on scale. They will soon open two cafes at the Bengaluru International Airport and also enter into strategic partnerships to scale impact. Employees are picked from partner organisations in the disability inclusion space and through self-mobilisation attempts to rehabilitate people from the street. The two experiential training centres started during the pandemic will continue to train people.

“Once a Mitti Café is set up, it is self-sustainable for a lifetime. For the initial capex, we have different corporate organisations support us in the form of grants, facilities, etc. Our first employee Kirti came in crawling for the interview. Today, she sits on a wheelchair and manages 10 people. We want to empower other women like her and make their dignity a reality,” concludes Alina.

(This copy has been updated to correct a typo)

Edited by Megha Reddy