This woman biker from Arunachal Pradesh is giving traditional Monpa clothing a new twist

Tenzin Metoh is the founder of Oro Bruk, a startup that specialises in traditional clothing lines of the Monpa tribe in Arunachal Pradesh, by giving it a new spin with different fabrics and colours.

The first woman to ride a Ducati Multistrada on a four-day expedition through Arunachal Pradesh terrain, Tenzin Metoh rides a Bullet 350cc Classic to the office.

A public health and engineering consultant with the state government in Itanagar, Metoh’s life is only partly on the fast lane. A bike aficionado apart, Metoh is also the founder of Oro Bruk, a startup that has given a new spin and lease of life to the traditional clothes of the Monpa tribe she belongs to.

Born and raised in Bomdila in the West Kameng district of Arunachal Pradesh, Metoh remembers a ‘magical’ childhood waking up to icicles she would prise off the window pane and constantly look at the snow outside.

“It was an idyllic existence, growing up in a small town. Being around my brothers, the talk always veered towards cars, bikes, and video games. I dreamed of owning a bike someday,” she tells HerStory.

Life on the fast track

Metoh moved to Delhi for her undergraduate course in Geography and a master’s in Sociology at Miranda House. She says she dabbled in a lot of fields, including media, before deciding to return to her home state and join the government.

In between all these, her love for riding bikes did not wane. “People ask me how I was able to handle heavy bikes. I tell them I would practice sitting on the bike first, and slowly learn to ride it,” she says with a laugh.

Her dream of owning a bike came true when she bought a Bullet in 2017 with her mother’s help. Unfortunately, it was stolen even before it was registered, dampening her spirits, but not her enthusiasm for riding.

In 2022, her passion came full circle. Metoh was invited to be part of the Explore Beyond exhibition, a collaboration between the state’s Ministry of Tourism and Ducati. One of the four-women team, she rode a Ducati Multistrada exploring the scenic beauty of the eastern part of the state, spending time with indigenous tribes, sampling local cuisine, and soaking in diverse cultures.

The experience was both liberating and insightful, she says.

“I was riding with professional riders. I did a 150 kmph speed. But these women were touching 170 kmph, and sometimes it was difficult to keep up with them.”

“Till then, I was not active on social media. As part of the contract, I had to communicate with people. In hindsight, it was a good idea, because I was able to connect with a number of women riders. Till then, I was riding with men, but this brought about a whole new world of discovery,” she adds.

Tradition, with a twist

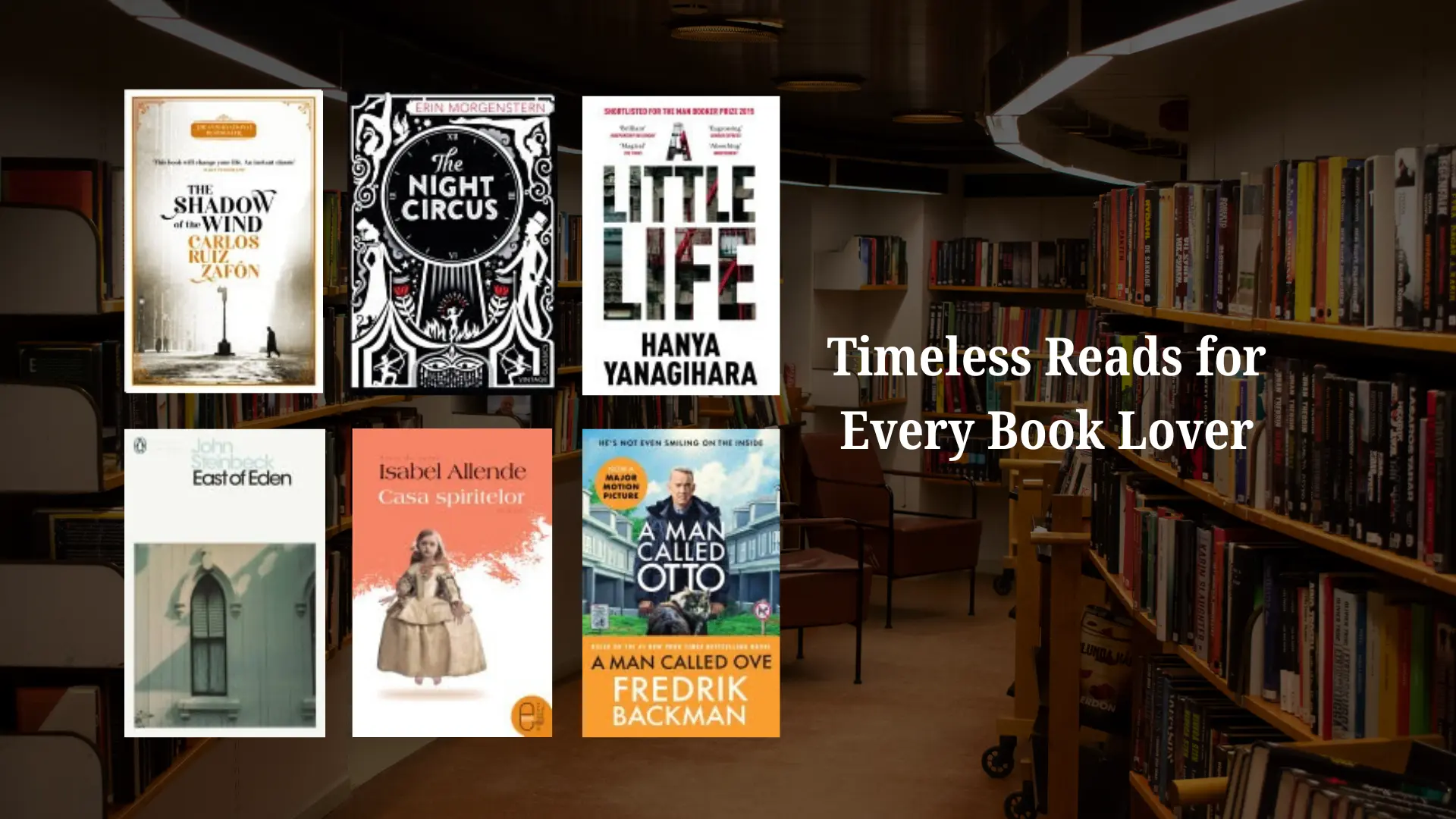

Some designs from Oro Bruk

Besides her regular job and biking pursuits, Metoh is also the founder of Oro Bruk, a startup that is giving the traditional attire of the Monpa tribe a new twist.

“All my life, I had seen maroon being used as a standard colour in Monpa attire. I happened to listen to a chance conversation between my mother and my uncle who were talking about blue being used in the olden days. I thought, my mother, who is a businesswoman, should try to revive the old colours. But she didn’t have much time and the onus fell on me,” she explains.

When she designed the traditional Monpa attire in other colours like blue, it stirred up a lot of controversy within the tribe. People accused her of destroying the culture and she was trolled online. Initially, she didn’t even think of developing a business, but just design 10 sets for her and her family to wear. But the initial investment warranted her selling the products, and despite the criticism, she continued with her idea.

“I didn’t want to look weak, or scared. So, I continued making them, especially the bags that are exclusive to the community, and which no other company had succeeded in replicating,” she adds.

The main attire of the Monpa are Shinka, a gown; Toh-dung, an open-front silk shirt, and Chuba, a loose garment worn by women. These are available in other colours like green, red, yellow black, blue, and a tinge of blue and green--mostly representing the five elements of nature. For everyday wear, she has designed the gale with Monpa motifs and designs.

Usually, these were made with yak wool to battle the winter, but with the region getting warmer because of climate change, she decided to use cotton instead. These clothes, generally worn on special occasions, started finding favour with young people who had rejected them because of their impracticality of wear.

She also designs accessories like handbags, belts, and jewellery. For men, Kanjar is an important attire, which has a lighter material like fleece and brocade to make it look trendy.

“Also, in Tawang, on the 15th of every month, it’s a practice to wear traditional attire. These lighter and comfortable options have become a hit,” she says.

She sources raw material from local suppliers that mostly use organic dyes. These are sent to women weavers working in different clusters in interior parts of Tawang. A lot of effort and money goes into research and development. The plans are to identify specific villages and clusters for the work. College students also learn and take part in the process.

“These outfits are sold locally, and popularised through social media platforms like Instagram and Facebook. We are trying to collaborate and work with NGOs to expand this craft. I also participate in many exhibitions and expos and I am trying to connect with as many self-help groups (SHGs) as I can,” she adds.

Metoh says, after three years, and the acceptance after the controversy, Oru Bruk has started making profits. People are opening up to new modifications, and slowly warming up.

She admits that traditional Monpa attire like the Shinka is expensive and can go up to Rs 25,000 a set or more. But she tries to keep the costs down and sells it for around Rs 12,000 and hopes to bring it down further if there is an increase in demand. The bags are priced between Rs 3,000 and 10,000.

“We are looking to scale this by introducing digital designs for those who cannot afford handwoven ones. Without collaboration with the government and artisan groups, this is not possible,” Metoh says.

Edited by Megha Reddy