Where is Nari Shakti? Decoding women’s participation in Lok Sabha elections 2024

On June 3, the ECI said that 31.2 crore women voters participated in the 2024 Lok Sabha elections, where only 797 women out of 8,352 candidates were in the fray. Why are the women missing in Indian politics? HerStory decodes.

In a country of 140 crore population, India saw a record-breaking 64.2 crore voters exercising their universal franchise—fighting scorching heat—in the recently concluded Lok Sabha elections.

Women voters accounted for 31.2 crores of their registered voter base of 41.7 crores in the world’s largest democracy.

31.2 crore women exercised their franchise in the recently held Lok Sabha elections. Representative image.

In fact, women outnumbered men with a turnout of 63% in the fifth phase of the seven-phase elections for 49 constituencies in six states and two union territories.

Despite these striking figures, the number of women candidates in this election seems quite small—less than 10% of the candidates fielded by different parties were women.

The Election Commission of India said the Lok Sabha elections saw 797 women among 8,352 candidates in the fray. In 2019, this number was at 767—an insignificant increase in the larger scheme of things.

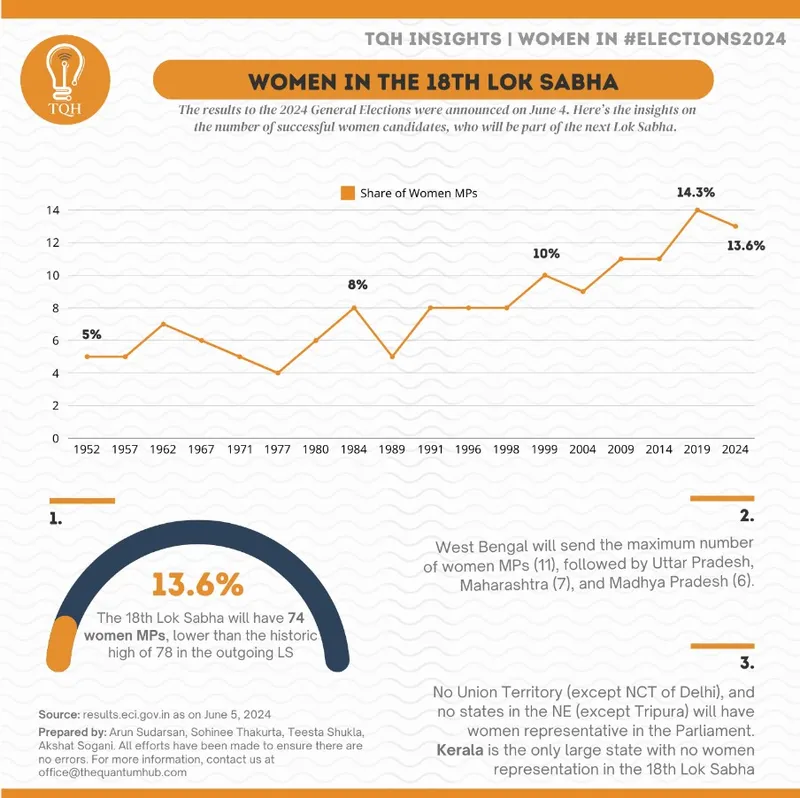

According to a series of factsheets on women in elections released by The Quantum Hub, 150 constituencies (27.6%) had zero women candidates.

Now remember, the government passed the 128th Constitutional Amendment Bill, 2023—a Women’s Reservation Bill—in the parliament in September 2023, ensuring 33% of the seats for women in the state legislative assembly and the Lok Sabha. In fact, at the time of passing this bill, the strength of women legislators in the lower house of the parliament was at just 14%.

The ECI data also shows that the Naveen Patnaik-led Biju Janata Dal (BJD) in Odisha and the Jharkhand Mukti Morcha (JMM) were the only parties that offered 33% reservation to women.

The 18th Lok Sabha will have 74 women MPs.

On counting day on June 4, only 74 out of 797 women candidates won compared to 78 in 2019. Among them, Bansuri Swaraj, Kangana Ranaut, Hema Malini, Supriya Sule, Dimple Yadav, Kanimozhi, and Misa Bharti relied either on star power or backing by strong political heritage.

Interestingly, 25-year-old Sanjana Jatav, an Indian National Congress (INC) candidate from Bharatpur, Rajasthan, became the youngest Dalit woman to win the elections.

These numbers raise several pertinent questions, and rightfully so.

Why do only a few women participate in politics when they come out in large numbers to exercise their right to vote? What social and economic factors prevent them from having political ambitions? What can parties do better to attract more women into the political fray?

HerStory speaks with politicians, political analysts, and representatives to understand the reasons behind the disparity, and the many contours of the social fabric that play a role in women’s active participation in politics and elections.

Arun Sudarsan, Public Policy Manager at The Quantum Hub—a consulting firm that works at the intersection of public policy and communications—says the number and share of women candidates in this election has been the highest ever, despite a minuscule rise.

“Parties (unrecognised or recognised) fielded more than 10%—national parties (11.84%), state parties (14.37%), and unrecognised parties (11.18%). It was only 7.09% among independents. That's why the overall number is only 9.57%,” he explains.

In 2009, only 556 women candidates (6.89%) women participated, followed by 668 candidates (8.1%) in 2014 and 726 candidates (9.02%) in 2019. “This year, we have 797 candidates (9.57%). So, I think we do have an increasing trend of women candidates,” he adds.

Why are women missing in Indian politics?

In India, one will find a skewed female-male ratio in almost every sector. “Even the corporate sector is skewed towards the male population. Historically, this is also how politics has been. It’s associated with power as much as public service, and men have occupied these positions of power,” says Lakshmi Ramachandran, General Secretary of Tamil Nadu Congress.

Meanwhile, Rimjhim Gour, Political Analyst and Founder of Sapiens Research and Analysis, has an interesting take. “The problem is that all parties either use women candidates to contest from safe seats or give them seats they are going to lose to send across a message. We see very few women contesting battleground seats.”

She believes the winnability quotient is a strong factor while fielding winning candidates. While the assembly elections are a lot more favourable to women in battleground seats, parties do not want to take a risk in the fierce Lok Sabha elections.

In this election, Rimjhim’s political consultancy worked for the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), mobilising female voters by working with over five lakh women’s self-help groups (SHGs).

Fouzia Khan, a prominent member of the INC and Rajya Sabha member from Maharashtra, believes money and muscle power are the big reasons for the low trends.

“Additionally, the inability of women to assert themselves within their respective parties and organise and form their own parties are contributing factors to the low number of women candidates,” she adds.

Actor and BJP politician Khushbu Sundar says we can’t allow men to call the shots. “We need women who are ready to take power into their hands and run the show. Unfortunately, we don’t have many women like that.”

The backing of political parties

According to The Quantum Hub, in the 2024 election, BJP fielded 70 women candidates (15.91%), followed by INC (41, 12.42%), CPI(M) (6, 11.76%) and the BSP at (39, 7.99%). The Trinamool Congress (TMC) fielded 12 candidates (41.3%). The Aam Aadmi Party had no women candidates.

Sudarsan says it’s interesting to compare the numbers between independent women candidates and those fielded by seasoned political parties.

‘If you look at recognised political parties—national plus state parties—they nominated 232 candidates out of 1,849 candidates. That's 12.55% of women candidates. Among independents, this percentage falls to 7.09%.”

While it is a high number—277 out of 3,909 candidates—it is very low in terms of overall share of candidates participating in the elections.

He believes that political parties are the best place to groom, encourage, and ensure more women candidates become political leaders in their own right.

While the 128th Constitutional Amendment Bill, 2023, or the Nari Shakti Vandan Adhiniyam, will be effective after 2026 post the next delimitation exercise, the 73rd Constitutional Amendment Act presently reserves one-third of electoral seats for women in Panchayati Raj Institutions (PRIs).

Under the law, India has seen active participation from women in local governance with over 1.45 million women shaping local decision-making. Currently, 20 states have 50% reservation for women in PRIs.

Every party, Rimjhim says, needs to start small and understand that one can’t straight away give tickets for the Lok Sabha elections.

“Start with the municipal and corporation elections. Activate the mahila (women) and youth morchas. Give them responsibilities and activities and push them into the forefront,” she says.

Lakshmi agrees. She says, “Encourage women’s participation from the ground up with local governance. They will learn how to operate within a political party, slowly make it to the next tier—the assembly—and the top tier, the parliament.”

In fact, political parties have started figuring out how to approach women electors in India in terms of identifying issues that resonate with them.

Sudarsan says, “When political parties start talking about relevant issues, they will be able to attract more women to join politics and be nurtured and become leaders. It is impossible to imagine a situation where, if issues were not relevant, women would be even interested to be part of that gruelling process.”

Fouzia emphasises that to attract more women, parties should actively promote female leadership, provide mentorship programmes, and ensure a supportive environment for women candidates.

Socio-economic challenges

Politics is gruesome. Add some patriarchy and the dominance of a boy’s club, vicious trolling, and the cost of contesting an election to it, and we have—no surprise—fewer women candidates.

According to Fouzia, a lack of family and societal support, coupled with the often-sordid nature of political mudslinging, frequently deters women from entering politics.

Khusbhu concurs. “I think women don’t get enough support from their families because politics is not a part-time job. You need women who are ready to give up everything and people to support them. Also, women go through the guilt of not giving enough time to their families.”

Elections and money go hand-in-hand. It costs a lot to fight an election. Rimjhim says, “One reason why tickets are given to women who are “someone” is because they will be able to afford the spending. This is a very big bottleneck that deters the youth and women from contesting elections.”

To counter this, a spending limit should be enforced strictly, and parties need to support these women financially.

Women are also easy targets for online trolls, she says, falling prey to scathing, vile personal attacks and online shaming. “Women face gendered attacks from all quarters. This behaviour, rooted in societal biases, inhibits women from making strides in their political careers,” she says.

Khushbu knows this all too well after being subjected to vicious attacks online. But social media “cannot define you or your strength”, she reiterates.

“Women do not realise their shakti (power). I want women to take challenges head-on and say, ‘I can do it.’ She doesn’t need a man to decide for her. Once she understands this, she can take up anything in this world, including politics,” she says.

(The story has been updated to include the number of women candidates from Trinamool Congress.)

Edited by Suman Singh