This startup’s devices can help more than 20 lakh manual scavengers globally

JALODBUST is a system that aims to rid the involvement of human intervention in septic tank cleaning with its IoT based technology and easy operation.

Despite several steps taken to combat manual scavenging in India, the process continues even today. Faecal sludge from septic tanks, leach pits and manholes are emptied through human intervention, exposing labourers to not only health risks, but also drudgery and social ostracisation, especially during these pandemic times.

Manual scavenging has been deemed illegal for a long time now according to The Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavengers and Their Rehabilitation Act, 2013. Yet, alternatives are still not available, thus creating an age old community of such workers who are unaware or ignorant of the risks such work entails.

However, in a historic move to end this practice, the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment will bring amendments to the above mentioned Act, as announced on World Toilet Day on November 19.

Co-founders Rakesh Kasba and Erica Kasba

But thinking ahead and finding a solution for this problem are Bengaluru-based Rakesh Kasba and Erica Kasba, who’ve mechanised this process with their system, , launched in 2018, through their company Cherries Engineering and Innovation India Pvt Ltd (CEII Pvt Ltd).

JALODBUST is a mechanized scavenging system that removes faecal sludge from septic tanks. Its primary objective is to eliminate human contact with faecal waste. “The device is aimed at relieving manual scavengers from contact with sludge. The people who work with buckets and shovels dealing with human wastes, will be given a pair of gloves and a switch instead, aiding their cleaning efforts,” co-founder Rakesh Kasba tells SocialStory.

He says with increasing number of toilets, JALODBUST is eliminating the need for human intervention in this sector altogether.

Creating JALODBUST

After working in the Government sector for 21 years, IIT alumnus Rakesh moved on to private sector jobs in Hydropower for about seven years, mostly in the Himalayas and the North East. During this time, he realised that people in the bottom-most layer of the social ladder were facing severe challenges. The realisation struck him all the more after he saw the viral picture of a small boy crying next to his deceased father who happened to be a manual scavenger.

Around the same time, a hackathon event, which was also attended by waste workers, opened Rakesh’s eyes to the ground reality. One of the workers stood up and said, “Even though engineering is advancing day by day, no engineering solution has been created to aid manual scavenging efforts.”

That’s when Rakesh and Erica, both of whom have an inclination towards finding solutions for social problems, decided to find a way through this long standing issue. He began investigating more into the problem, and tried to find out why due engineering ideas and processes had not been applied earlier.

“The last patent in the sector of faecal sludge handling was made in 1966 for the vacuum tanker, before which we had the septic tank system standardised in 1940. Thereafter, we’ve seen nothing new,” he says.

Rakesh Kasba (middle) explaining the working of JALODBUST in Bengaluru

“As per estimates, 450 crore people across the world depend on on-site sanitation toilets. And for every one of these toilets, where the faecal waste goes into a tank, there is a call for manual cleaning. Globally, almost 20 lakh labourers come in direct contact with faecal waste while trying to clean it and keep the tanks functioning,” he adds.

Using his engineering knowledge, Rakesh was able to formulate a solution to rid the faecal sludge through JALODBUST.

“JALODBUST is derived from the name ‘Jalod Bhava’, a demon that was believed to reside in the Kashmir lake. According to folklore, the demon was allowed to grow until he began to kill the people who helped him grow,” says Rakesh, explaining the idea behind the name. He further adds that the demon was killed by summoning all the power on the earth. He associates his product to a similar concept.

Machine replacing human intervention

JALODBUST is a system that, even in its small form, aims to provide ‘smell, sight and splash’ free handling of faecal sludge for workers.

“More importantly, their work will become drudgery-free. The use of JALODBUST will also improve their social status and help them live without stigma,” he adds.

The sludge remains at the bottom of the septic tank over the years, where it densifies after settling. Due to the semi-solid state of the sludge, it cannot be pumped out, and thus needs to be removed through manual intervention.

Well-paying sanitation entrepreneurship is the only humane solution to get this work done and JALODBUST is doing this through two of their devices – Pride and SaniPreneur.

Pride, the smaller of the two devices, helps pump out the sludge from the septic tank. The device can easily navigate through buildings and basements without coming in contact with people.

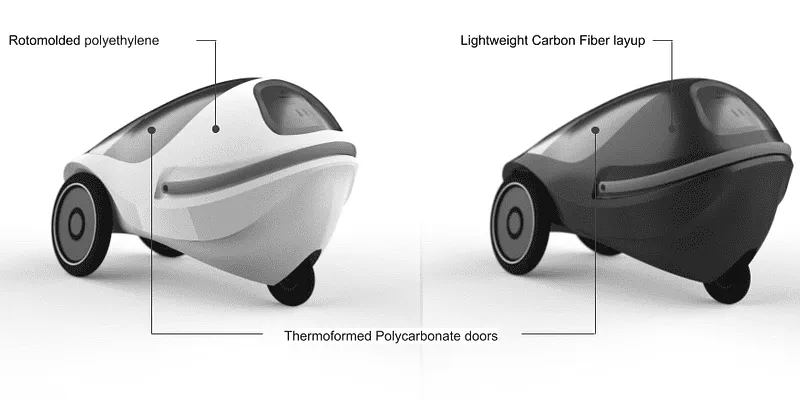

A model image of JALODBUST Pride

SaniPreneur emits low-power hydraulic shock waves that dislodge, liquefy and extract the faecal sludge. Operated on a Lithium-ion battery, with a smart control panel and an IoT dashboard, the device can replace the shovel and bucket of the manual scavenger.

While both the devices can be single-handedly operated, the devices do not actually take away the labourers’ jobs, but in fact, creates a shift in livelihood for these workers.

“The faecal sludge when extracted is up to 10 percent solids, which when dried and made pathogen-free becomes nutrient rich manure and soil conditioner selling at Rs 5-10 per kg. That means for every trip of SaniPreneur, it will generate Rs 500-1000 income from sale of this material,” Rakesh explains.

After over a year of research, the device is in its pilot phase, being tested in many places around Bengaluru. In the coming months, the company plans to expand while making the device more user-friendly.

Trial run in Weaver Colony

In April 2020, JALODBUST was declared the winner at ASME ISHOW (Innovation Showcase) 2020 and recognised for their work towards the upliftment of sanitation workers. The company was also recognised by Smart Bio Awards as the Best Social Enterprise on the final day of the recently held Bangalore Tech Summit 2020.

Challenges on the way

Talking about one of the biggest challenges in the expansion of this project, Rakesh says that lack of funding is a hindrance at the moment. Apart from a small micro-grant from HelloScience, a partner-driven startup accelerator, “the project is almost completely bootstrapped,” he shares. However, it has received one year of fellowship from Social Alpha, supported by Tata Trusts and got cash and in-kind award from ASME.

Since most of the components of the device, except the batteries and the motor, are completely new and require manufacturing, JALODBUST is hoping for a fund infusion of Rs 50 lakh to Rs 1 crore to use the existing technology and scale it to a usable product in the next six months.

Road ahead

While building a device, that has a life of at least 10 years, can take at least six months with the necessary funds, Rakesh and his team have also laid out other designs on the table to smoothen the process of self-propelled sewage management through creation of safe, dignified and well earning livelihoods.

“We want to create a system where this sludge can be converted into manure and be linked directly to farmlands after necessary processes,” Rakesh says. “We want to ensure that the sewage is controlled, but without anyone having to come in direct contact with the waste.”

Edited by Anju Narayanan