[Product roadmap] Starting out on WhatsApp, how Dunzo became India’s go-to hyperlocal delivery startup

A product roadmap clarifies the why, what, and how behind what a tech startup is building. In the second article of this series, we take a closer look at Bengaluru startup Dunzo, which began life in 2015 as a WhatsApp service, and is now synonymous with getting your tasks done.

Need something now? Just Dunzo it!

Founded in 2015, Bengaluru-based is your personal concierge – from filling out shopping lists to picking up the charger you forgot at home or delivering your favourite pizza to your office, it does it all.

On-demand startups succeed by addressing a latent need in the market. and did it; so did and .

Dunzo addressed the problem that most time-strapped people face today: the need to get things done.

The app, which now has multiple functions, categories, flows, and even a B2B version, started life on WhatsApp. Users would type out what they needed done, and Dunzo would get to work.

It’s well known that people keep returning to a product because it solves a need.

“Dunzo, even on WhatsApp, was doing that. There were several problems - you can’t track a partner, you can’t pay in advance, you don’t know if your delivery is going to come on time - and yet there were early adopters,” says Mukund Jha, Co-founder and CTO, Dunzo.

But what started as a simple list app soon opened up multiple possibilities. From WhatsApp, it moved to a messaging app, then to an app with different categories and workflows. The list still exists, but the workflow has become more organised and “catalogued”.

Founders of Dunzo - Kabeer, Mukund, Ankur, and Dalvir

But why the shift?

By the time Dunzo built the catalogues and categories, the app had a loyal base of consumers and was getting 500 orders a day just through WhatsApp.

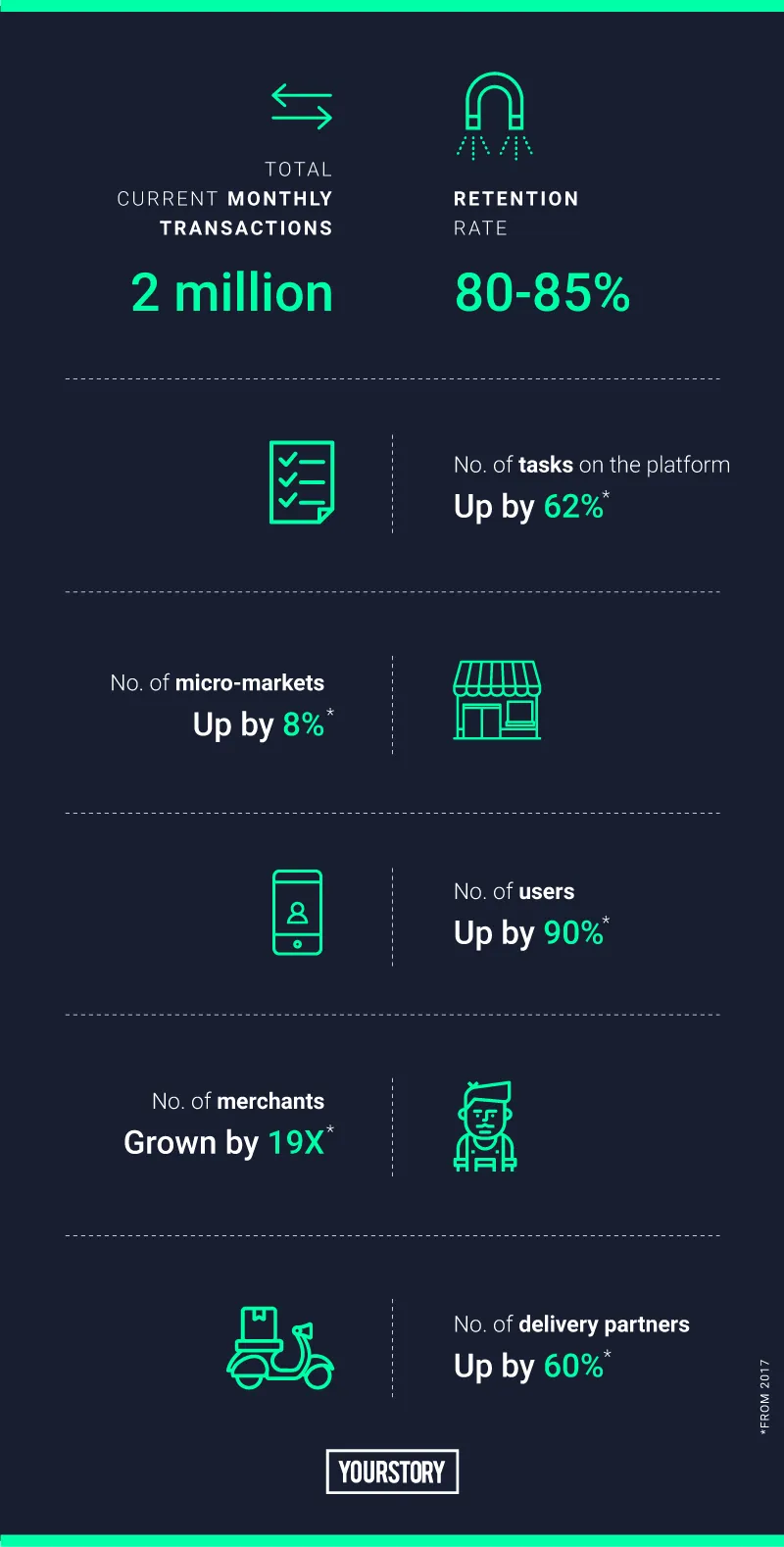

Today, Dunzo does over two million transactions in a month, and has a retention rate of 80-85 percent.

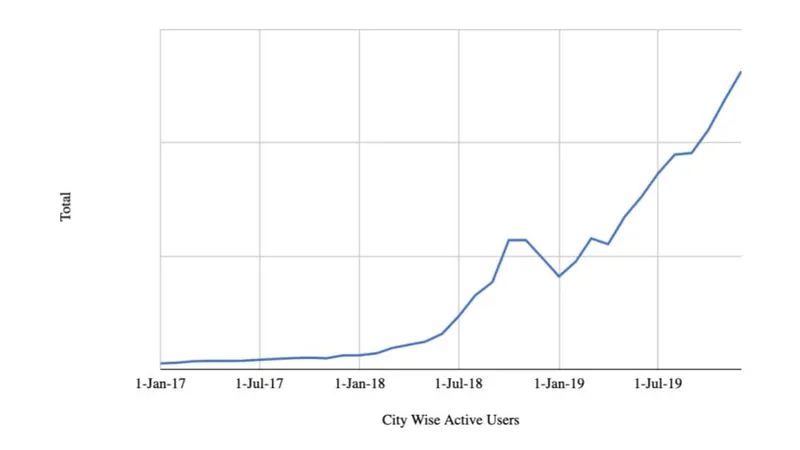

The growth has been exponential. The number of tasks on the platform has shot up by 62 percent, the number of micro markets it serves is up by eight percent, user base has increased by a whopping 90 percent, and merchants have grown by 19x.

This scale couldn’t be achieved on WhatsApp. It meant building their own app and, if needed, different versions.

Growth by numbers

D for Dunzo, D for delivery

It all started one afternoon in 2015 at a restaurant in Bengaluru. Kabeer Biswas, who had completed his earlier startup Hoppr’s transition to Hike, was in the city.

He thought how nice it would be “if there was someone who could complete your list of tasks for you — just tell someone what you need finished and it is done.”

That thought led to the first version of Dunzo, a WhatsApp service.

Dunzo soon began completing tasks for its users. It started with a small set, but the user base grew. By the end of 2016, the startup was getting over 500 orders a day.

When Kabeer and his co-founding team, Ankur Aggarwal, Dalvir Suri, and Mukund Jha, were testing the market in 2016, they focused primarily on building the partner app.

Dunzo, like any hyperlocal on-demand delivery platform, had to ensure that delivery partners were able to fulfill the orders.

So, while the clients used WhatsApp, the message would reach partners via the partner app.

“We chose to build the partner app first because that is where most of the scaling challenges were. Telling the partner which location to go, what product to buy, ensure smooth interactions, track money, and so on,” Mukund says.

The first app - Messaging ++

It was April 2017 when the Dunzo team built the consumer version of the app. It was time as the orders were growing, and the team realised that they needed their own app to scale.

Mukund says they were “looking at 5x scale then”.

As most workflows were on WhatsApp, the team decided to build the same interface on their app. It was just Messaging ++. A user would type out a list of what needed to be done, and a partner would complete the tasks.

“Now that the need was established, we wanted to move users to our own platform. WhatsApp just wasn’t scalable,” Mukund says.

The team took six months to build the first app. “In hindsight, we should have deployed faster. We were being too picky and focused on fonts and designs,” Mukund says.

The app-building process started in 2017 and continued to the end of 2018. By then, Dunzo was touching close to 80,000 orders in a month.

The first version of the Dunzo app

But the task management app ran into a glitch. Only chat-based systems weren’t working as Dunzo was looking to scale.

The startup had just picked up $17 million funding from Google, the search engine’s first direct investment in an Indian startup. This shot Dunzo into the spotlight, and it had to iron out the wrinkles in the process.

“The consumer today, accustomed to ecommerce, is used to a certain flow. They want to know when the order will be delivered. They want to be able to pay for their order and not keep answer a call by a partner for their order. The friction we had in our first app was high,” Mukund recalls.

Today, while lists still exist, they contribute to less than five percent of the overall orders placed.

The first app

Reducing human dependency

The team realised that human intervention in completing every single order was high. After a list was submitted, partners needed to locate stores, and/or call users to confirm product availability, which led to final confirmation.

“Growing the product would also mean increased human intervention, which would be a cost problem and meant a certain inconsistency,” says Anirban Das, Head of Products, Dunzo.

Anirban joined Dunzo in 2018, with one mission: to build a scalable product.

Many users then found the app confusing – when to make payment, where was the catalogue of items, and more. That was a problem from a new user acquisition and activation standpoint.

Even after the order got placed, fulfillment took long from a partner standpoint.

“A confirmation was needed, the partner would send photos of items, the user would be busy. The partner would be stuck at the store… there were too many steps,” Anirban says.

That is when the idea of cataloguing came into play.

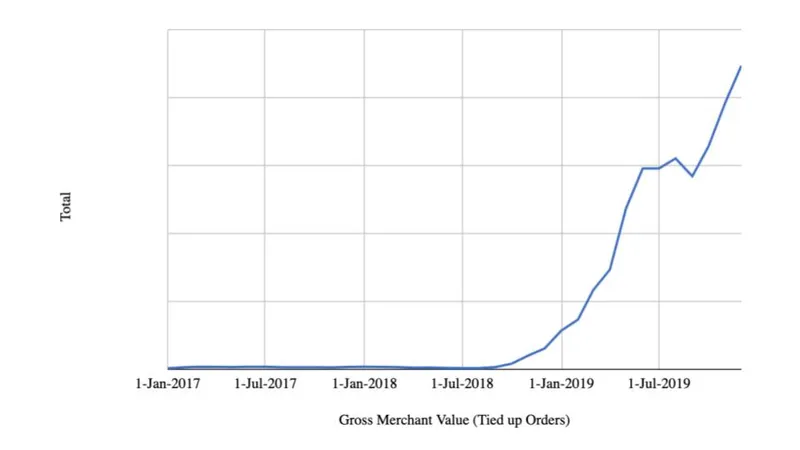

The GMV

Cataloguing the world

Unlike a regular ecommerce or food delivery platform, Dunzo dealt with multiple variables. From finding spectacles to onions, the app needed to provide for everything.

“I keep saying this: we are cataloguing all items in the world and are running multiple companies in one. The workflows are different. The app and algorithms needed to be built to catalogue and search everything in the store. It also meant matching the best partner with the user,” Mukund says.

The idea was to improve efficiency. This involved matching demand and supply, focusing on different geographies, ensuring partner positioning in those geographies, and working on real-world flows.

For example, for medicine delivery, the system should be able to detect prescriptions and work on that. In other stores, the system should know items that are out of stock and those with changing prices.

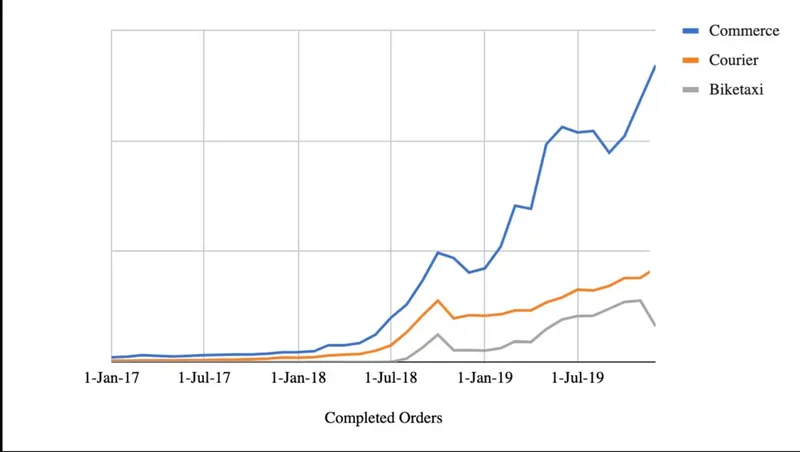

“When we started the first algorithms, bike taxis weren’t in the picture. So everything was designed so that a task came into the system, and had a wait time. We realised we could use the partner supply. The partner would finish a task and wait for another. Bike taxis helped,” Mukund says.

An AI-based, text auto-suggesting app could have been a solution for cataloguing, but it had several constraints and other factors were also involved.

“We had tried bots, but that didn’t work earlier. We are now relooking at that as some queries can have automated responses,” he says.

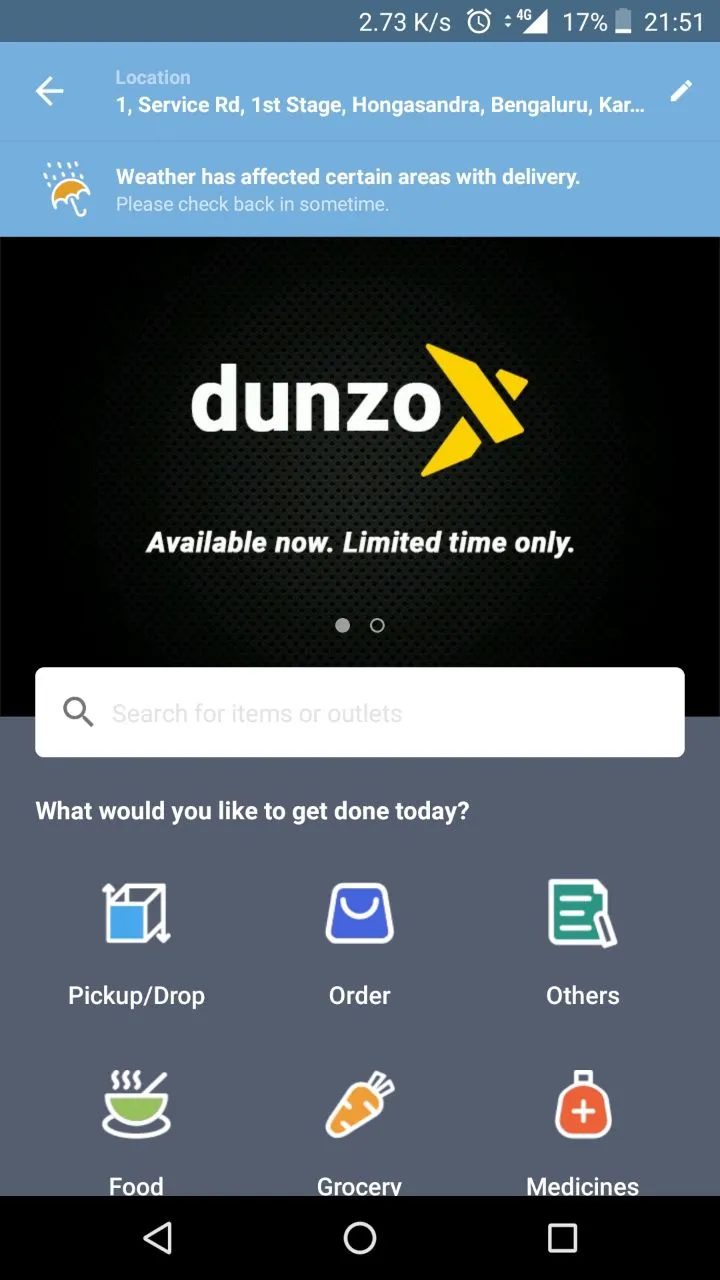

The new Dunzo App

Building a strong feedback loop

Change is essential, but how does a startup decide what changes need to be made? Mukund says feedback loops and the willingness to listen play an important role.

“There are two ways. One is direct feedback from loyal, invested users. The second kind of feedback is the data you generate on your platform - frequency and retention. If people use your product frequently it means you’re doing something right,” he says.

Data analytics helped Dunzo find patterns and better understand what the user wanted.

“We saw a lot of people coming on the app at 12 pm and placing orders. The spikes at a particular time led us to work on scheduled flows. We have now moved that to our B2B app as people send multiple orders in short time frames,” Mukund explains.

The Overall Dunzo User Growth

Killing certain features

But feedback loops and data also mean hiving off certain categories. Dunzo made one such decision on alcohol delivery, but that was more for legal and regulatory reasons. The startup also shut down services like home repair, as the category didn’t bring frequency or number of users.

“We wanted to focus on a few things and not spread ourselves too thin. That has been one of the biggest challenges at Dunzo. We have so many different categories, and there are established competitors in each category with more resources and people,” Anirban says.

This makes user preferences the top vector. Dunzo focuses on the most popular categories and brings in complaints.

The demand in a hyperlocal cross category like Dunzo is very different. There are peaks in 'food' during meal times, and grocery races ahead when people reach home.

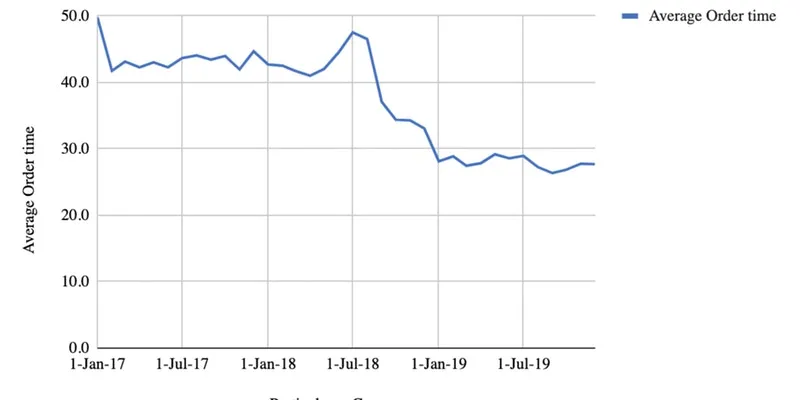

Average order times

“Commute times generally precede food peaks so can we get better utilisation by launching bike taxis,” Anirban asks.

The next vector is based on business priorities. Last year was all about growth for Dunzo; this year, the startup aims to keep growth steady while working towards profitability.

“We have rewritten multiple systems. We have 45 different products and services that work together to deliver the experience for our user partners and merchants,” Anirban says. But Dunzo is no longer the only one operating in the space today. Swiggy has its own offering: Go.

But the hyperlocal delivery app isn’t worried. “Competition will be there. But we have clear road maps. We are solving for what users want and what the next feedback loop needs,” Mukund says.

Dunzo Order Categories

Solving based on a structure

Anirban explains that the product team structure has been constantly evolving based on top problems from day one.

“Earlier, almost 50 percent of the product and engineering teams were working on the merchant side of the platform. Now it has stablised, so fewer product and engineering teams are focused on that,” he says.

The Dunzo team is at present focused on different problems. The last couple of versions of the product had specific outflows that could solve for multiple categories.

The idea now is to go deep into each category and bring out the differences.

“For example, grocery and medicines differ when it comes to consumer behaviour. We are looking to first solve for the groceries, fruits, veggies, and meat category. Over 700 SKUS are ordered frequently by our consumers; how can we make the experience better?” Anirban says.

The second focus is partner experience, and improving new partner retention. How can Dunzo rework earnings per hour for the partner? This has to be done keeping in mind that the distribution of earnings for the startup stays within the band it needs to scale, while ensuring fairness and keeping costs under control.

Dunzo Partner

Dunzo has launched a new vertical, bike taxis, and wants to work on improving the product and operations. Next in line are quality and support experience—the startup aims to reduce the response time for customers.

Last, but definitely not the least, is the focus on growth and new users.

“Technology comes into the picture when you want to scale things and make things more efficient. We have solved one loop; the idea is to make systems more efficient and user-friendly at every step and stage,” Mukund says.

(Edited by Teja Lele Desai)

![[Product roadmap] Starting out on WhatsApp, how Dunzo became India’s go-to hyperlocal delivery startup](https://images.yourstory.com/cs/2/a9efa9c02dd911e9adc52d913c55075e/Dunzoproduct-road-map-1581520789482.png?mode=crop&crop=faces&ar=2%3A1&format=auto&w=1920&q=75)

![[Product roadmap] Ezetap began with a single payments offering and decided to pivot to a SaaS model](https://images.yourstory.com/cs/2/730b50702d6c11e9aa979329348d4c3e/BhaskarChatterjeeEzetap1-1580969581924.png?fm=png&auto=format&h=100&w=100&crop=entropy&fit=crop)

![[Techie Tuesday] From working on Google’s search platform to co-founding Dunzo - the journey of Mukund Jha](https://images.yourstory.com/cs/2/a9efa9c0-2dd9-11e9-adc5-2d913c55075e/techi-tuesday_(800x400)1566210615008.png?fm=png&auto=format&h=100&w=100&crop=entropy&fit=crop)