Germinate, go, grow – how to succeed in the three phases of startup evolution

This valuable textbook provides aspiring founders with a wealth of research, stories, and frameworks. Here are some key highlights.

Launched in 2012, YourStory's Book Review section features over 300 titles on creativity, innovation, entrepreneurship, and digital transformation. See also our related columns The Turning Point, Techie Tuesdays, and Storybites.

Aspiring entrepreneurs will find a valuable collection of tools, roadmaps, and frameworks in Entrepreneurship in Developing and Emerging Economies, by Ali J Ahmad, Punita Bhatt, and Iain Acton.

The authors provide actionable insights into the pre-startup, startup, and growth phases of the entrepreneurial process. The material is well-illustrated with tables and diagrams, and reflection activities for readers. The 13 chapters are spread across 250 pages, with dozens of entrepreneurship examples from Asia and Africa.

Ali J Ahmad teaches innovation at WMG, University of Warwick. He also started up three ventures in Pakistan. Punita Bhatt is a research fellow at Aston University, and earlier headed Sony Corporation’s treasury in India. Iain Acton is co-founder and partner at innovation consultancy Disruptive Lemonade.

“Entrepreneurship drives innovation and creates new markets, which generates employment and new wealth,” the authors begin. To be effective, the teaching of entrepreneurship should be personally reflective, experiential and tactile. It applies to learners from all disciplines, not just to business.

Entrepreneurial thinking can be effective within large organisations also, in the form of intrapreneurs. People can take on an entrepreneurial phase later in life as well, after traditional employment.

The expertise required in the set-up phase is different from growth phase: opportunity framing, dealing with uncertainty, agile decision making, and managing risk, the authors explain.

Here are my takeaways from this useful textbook, summarised as well in the tables below. See also my reviews of the related books Startup Launchpad, Lean Startup, The Startup Owner’s Manual, Unfair Advantage, Design Your Thinking, The Business of Change, and Social Entrepreneurship in India.

I. Entrepreneurship: mindset and practice

The authors distinguish between enterprise and entrepreneurship: enterprise is the application of ideas for problem-solving, while entrepreneurship is creating new ventures in addition to solutions.

Enterprise skills include taking initiative, identifying opportunities, creative problem-solving, intuitive decision-making, getting buy-in, strategic thinking, and personal effectiveness. Entrepreneurship involves research, technical prowess, estimation, selling, communication, experimentation, and partnerships.

As practical exercises, the authors advise learners to spot local problems (eg., littering, water shortages), mull over the impact of the problem for a few days, and research and discuss possible solutions. Keeping a diary, shadowing experts, and interviewing local store owners also help.

Useful creativity techniques are storyboarding, six thinking hats (information, feelings, caution, benefits, creative ideas, management), and SCAMPER (substitute, combine, adapt, modify, put to another use, eliminate, reverse). Creativity barriers include rigid cultures and processes, organisational groupthink, shaming responses to failure, and cognitive blocks like confirmation bias.

The authors cite a number of examples of creativity at work: Prof Muhammad Yunus’ initial experiments with micro-credit ($27 in loans to 42 villagers), NeoNurture (incubator made from car spare parts), Jack Ma’s learning and branding practices (English as a tour guide, kung fu names for employees), and Steve Jobs’ Zen meditation techniques (making diverse connections).

While self-belief and pride are important, so are flexibility and adaptability, the authors explain. Activities like frugal innovation are quite popular in emerging economies, though jugaad is only a quick-fix that is not sustainable or safe at scale.

As notable examples, the authors cite Lijjat Papad (low-cost distributed manufacturing), MittiCool fridge (made from clay for rural markets), MakaPad in Uganda (affordable sanitary napkins from reusable materials), and M-KOPA Solar in Kenya (pay-as-you-go solar electrification).

Other examples are Klong Dinsor in Thailand (educational aids for the visually impaired), CEMEX in Mexico (fleet of concrete-mixing trucks), and Natura in Brazil (licensed cosmetics technologies from universities).

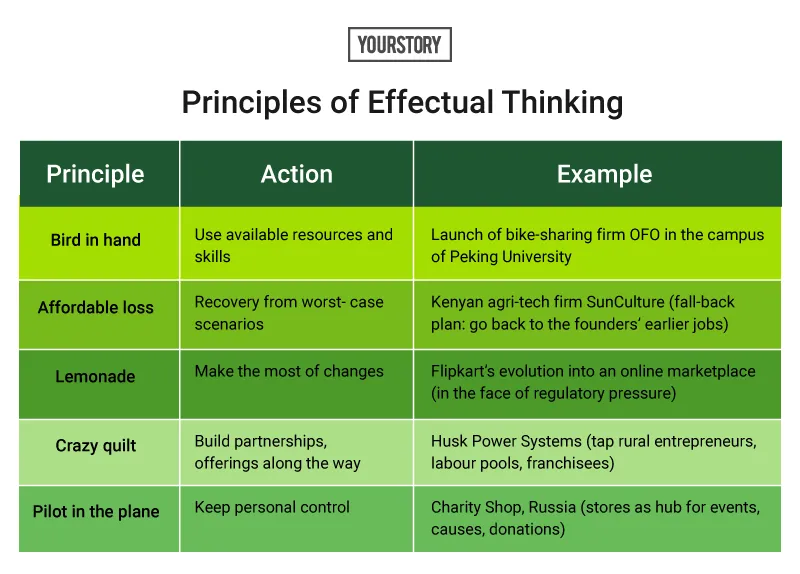

One chapter draws heavily on Professor Saras Saraswathy’s heuristics of effectual or entrepreneurial thinking in the face of limited resources, multiple paths, and uncertain environments (see my earlier article and interview). This is in contrast to causal or managerial thinking to achieve known and pre-determined goals (see my summary in Table 2 below).

II. Startup launch

Effectively solving customer problems calls for primary and secondary research, observations, and interviews. This can include domain trend analysis in online forums, observing how customers experience and solve problems, interviewing them, and conducting focus groups.

Useful clues to look for can be in the form of customer confusion or frustration, wastage of time, non-verbal communication, and even user modifications of products.

“There are two ways of recording observations – as a participant or a non-participant,” the authors explain. The entrepreneur can try to become an “insider” or a “fly on the wall.”

Active listening can call for a third person to observe the interview, or customer permission to record the interaction. Insights can be gleaned by asking open-ended questions such as Tell me more about, Can you give me an example how, What do you think of, or Can you explain why.

Use of focus groups calls for effective moderation, and consciously avoiding preference for participants’ views, the authors caution. This can lead to data bias problems. As research examples, the authors cite M-Pesa investigations into customer behaviour and agent networks,

The authors also draw heavily on innovation expert Clayton Christensen’s ‘jobs to be done’ framework, with a focus on customer types, job context and frequency, decision making, and use of existing solutions (see my book review here).

Entrepreneurs should address three kinds of customer jobs or tasks: core (based on needs), system-dependent (based on existing solutions), and emotional (personal, social). Based on this, a three-part solution decisions map should be drawn up.

This map can be then be used to define the market (job and customer), estimate market size, and identify customer willingness to pay. Customers tend to look for solution efficiency, affordability, convenience, and social perception.

The authors illustrate these principles in action through case studies of Airbnb and Chinese ride-hailing app DiDi Chuxing.

Building on this analysis, tools like Alexander Osterwalder’s Value Proposition Canvas help identify customer pains and gains, and how solutions can relieve these pains and deliver gains.

The value proposition should fill the value gap with a credible value creation promise, and be able to match cost, profit, and customer willingness to pay. The authors identify barriers to fulfilling this need and promise, such as customer doubt, risk perception, and habit inertia.

These principles are illustrated by drawing out the value proposition of the Apple iPod and OFO dockless bikes in China. The three value gaps lie in customer segments, decision choices, and switching to new solutions.

Ultimately, the entrepreneur should be able to frame a compelling, succinct, and even memorable value proposition statement and tagline, eg., A thousand songs in your pocket. In the future, this can be extended to new offerings and market segments as well.

The next step before launch is testing the value proposition via the lean startup and customer development frameworks by Eric Ries and Steve Blank. This is based on validated learning from build-measure-learn iterations to arrive at the minimum viable product.

Proposals, prototypes, and products should be evaluated in terms of customer education, early adopters and channels. The authors distinguish between qualitative testing (eg. customer understanding of the value proposition) and quantitative (eg. choice of effective channel).

“Smoke testing” (via landing pages of proposed but not yet developed products) and listing on crowdfunding sites are other ways of gauging customer interest and willingness to pay, the authors explain.

As examples of lean startup application, they cite the growth of Chinese drone leader DJI, Meituan food delivery app, and e-paper smartwatch Pebble Time.

III. Enterprise management

Once there is proof of concept and traction, founders need to engage with funders through pitching. As components of a good pitch, the authors list market research, problem and opportunity identification, business model, finances, partnerships, and team profile.

“Stories, out of all narrative forms, are the most memorable – practice telling your vision story prior to the pitch,” the authors emphasise.

Investors are looking for experience, knowledge, passion, commitment, and integrity in the founder. Leadership, vision, realism, and coachability are also important.

There is a fine line between being ambitious and unrealistic, the authors caution. Savvy investors have seen a whole range of pitches and can quickly discern those who seem not committed or grounded enough.

Good resources on pitch decks can be found on the numerous sites for crowdfunding and business plan competitions. Examples include Kickstarter, Indiegogo, and Catapooolt.

On the sales front, the authors document awareness approaches like introductory offers, free trials, demos, launch events, and affiliate partnerships. They should be targeted at specific segments, and customer testimonials should be systematically leveraged.

Highlighted sales approaches include social media (SELCO YouTube videos), word of mouth (Kayani Bakery, Pune), social media influencers (MissMalini.com), sidewalk posters, newsletters, and Instagram (City Cakes, Bangkok), and differentiation (Bakeys’ edible cutlery).

The chapter on finance highlights key indicators and metrics like break-even point, contribution per unit, debt to equity ratio, net cash flow, and net profit.

Avenues of funding include community members (eg. Rangsutra), bootstrapping and VCs (Mast Kalandar), angel investors (CresVentures), social venture funds (Aavishkaar), impact investment platforms (Ketto), microlending platforms (Milaap), crowdfunding for creative projects (Wishberry), and government grants (Nigeria’s YouWin, Vietnam’s Technology Innovation Fund).

The authors urge founders to pay close attention to vision, mission, and values statements, which will affect organisational culture, ethics, behaviours, decision making, governance, and even crisis management.

Vision statements reflect aspirations, while mission statements are a succinct declaration of strategy. Values like social responsibility are also reflected in brand identity. A range of social auditing and accounting frameworks has emerged over the years, such as Social Audit Network and Global Reporting Institute’s Sustainability Reporting Guidelines.

Cited examples are Rivigo’s model of truck driver relay systems to “make logistics human.” Its 10 values are captured in the “Rivigo Way of Life”, which includes boundless energy, respectful disagreement, frugality, data focus, and hiring better people.

Notable examples of enterprises with social or environmental impact are Karma Recycling (e-waste management and device refurbishing), Adorn Online (rural artisanal network), Thrive Agric (farmer support investments), HealthifyMe (weight management), WaterWalla (affordable potable water solutions), and Embrace Infant Warmer (affordable incubators).

Other cited examples are Mirakle Couriers (employing the hearing-impaired), Sakha Cabs (women drivers and passengers), Jayashree Industries (affordable sanitary napkins), Vortex Engineering (solar-powered rural ATMs), and Berman-Kalil affordable housing in South Africa.

The concluding chapter offers entrepreneurs tips in setting legal foundations, IP protection, business registration, and operational management in manufacturing and service industries. Cited examples are Katti Junction (franchise management), and GMW (EV manufacturer with battery swapping stations).

The book ends rather abruptly with this chapter. It would have been great to end with material on emerging entrepreneurship trends, the entrepreneurship education movement, collaboration between corporates and entrepreneurs, and some examples of serial or parallel entrepreneurs.

For an academic textbook, the reference section comes up short with a mere 14 sources, when there’s actually a wealth of books, journals and online resources on entrepreneurship out there.

Still, the authors have done a great job of integrating a wide range of entrepreneurship frameworks and examples, with numerous stories and tips. This is a must-read textbook for those beginning their startup journeys, and for entrepreneur support organisations and educational institutes conducting training programmes.

YourStory has also published the pocketbook ‘Proverbs and Quotes for Entrepreneurs: A World of Inspiration for Startups’ as a creative and motivational guide for innovators (downloadable as apps here: Apple, Android).

Edited by Megha Reddy

![[The Turning Point] How an accident influenced this entrepreneur to start healthtech startup Tattvan](https://images.yourstory.com/cs/2/70651a302d6d11e9aa979329348d4c3e/Ayush-Tattvan-11-1622188791145.jpg?fm=png&auto=format&h=100&w=100&crop=entropy&fit=crop)