Mapping, preparing, and bouncing back from failure – how founders can gear up for the bumpy journey of entrepreneurship

The emotional, social, and economic costs of startup failure can be severe. This must-read book shows founders how to map the failure landscape – and gear up for success.

Launched in 2012, YourStory's Book Review section features over 320 titles on creativity, innovation, entrepreneurship, and digital transformation. See also our related columns The Turning Point, Techie Tuesdays, and Storybites.

While much can be learned from startup success stories, there is a lot to learn from failures, mistakes, misfortune, lapses, and bad judgment. Forewarned is forearmed, and the lessons of hindsight and research can help founders avoid failures on their part as well.

Frameworks, stories, and lessons from startup failures are brilliantly captured in the book Fail-Safe Startup by Tom Eisenmann, professor at Harvard Business School. He has taught courses on launching and scaling tech ventures, entrepreneurial sales and marketing, and entrepreneurial failure.

Here are my key takeaways from this must-read 350-page book, summarised as well in the tables below. See also my reviews of the related books The Other ‘F’ Word, The Messy Middle, Who Blunders and How, Adapt, The Up Side of Down, The Wisdom of Failure, Fail Better, Fail Fast, and Failing to Succeed.

News of mistakes rarely makes it to the press, but fortunately, there are conferences like FailCon that help entrepreneurs analyse failure. See also my articles on Eight lessons in failure from Amani Institute’s Fail Faire and Exit Plan B: Where is your parachute? 15 tips for winding down your startup.

The book shares in-depth examples of failures of seven startups for reasons like the false promise (misplaced confidence from early success), false start (premature launch), and audacious goals (unsuccessful moonshots).

The material is thoroughly referenced (with 22 pages of notes and citations), and a 20-page appendix describes the systematic survey to which 470 startups responded. In many cases, the founders themselves participated in the professor’s classroom discussions, providing a wealth of first-hand insights.

Foundations

Tom uses the HBS definition of entrepreneurship: pursuing novel opportunity while lacking resources. “A venture has failed if its early investors did not – or never will – get back more money than they put in,” he adds.

In the bigger scheme of things, a startup can be struck by misfortune or circumstances beyond its control (e.g. competitor product, pandemic). A “good failure” is one that yields valuable spillover insights for society and the founders’ future journey, even if the startup shuts down (as seen in the social robot startup Jibo).

Entrepreneurial risk comes from lack of customer demand, inadequate tech systems, poor execution, and finance shortages. Failures are generally attributed to the “horse” (company, competition) or “jockey” (founder, team), Tom observes, while cautioning that there are multiple inter-related factors at play.

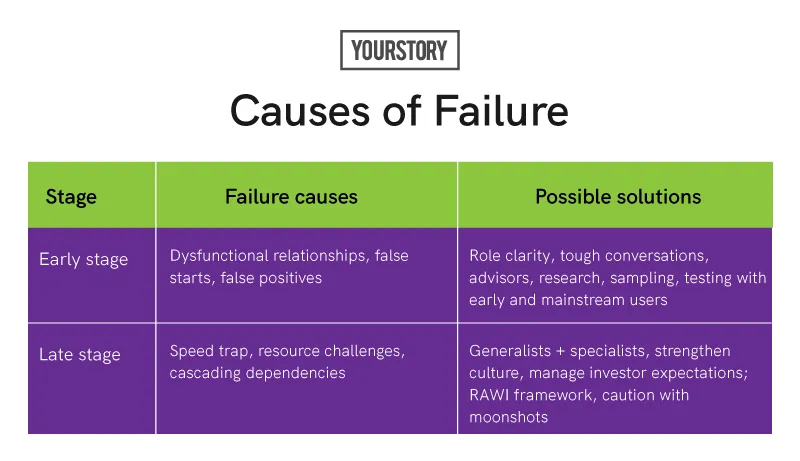

I. Early-stage failures

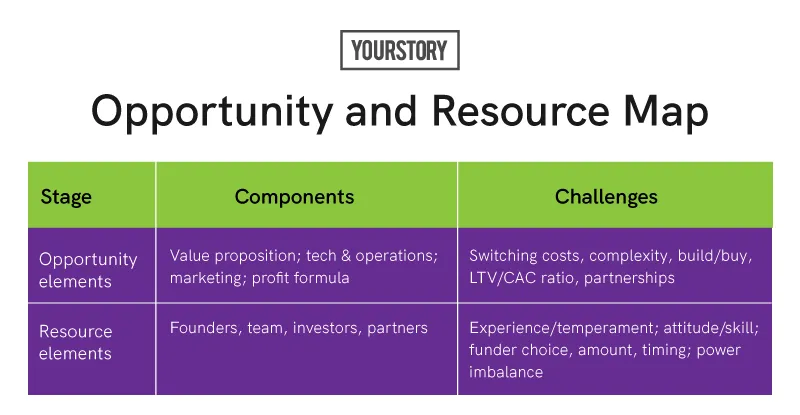

Tom uses an opportunity-resource framework to describe the startup landscape. The opportunity is akin to the horse, and the resources are the jockeys and other stakeholders. These issues and tradeoffs need to be weighed carefully and often in the startup’s journey.

1. Catch-22

The customer value proposition of the startup’s offering must be compelling enough to overcome switching costs and build network effects. Single segments are quicker and easier to target but may yield less revenue than multiple segments.

“Customers are drawn to products that balance novelty with familiarity,” Tom explains.

High-touch solutions offer differentiation but entail higher operating costs and difficulties in scaling. “Big bang” marketing launches can drive growth but are expensive.

Founder teams should have diversity (“hacker and hustler”). Confidence fuels resilience and attracts resources, but overconfidence can lead to too much risk and inability to pivot, Tom cautions.

He cites the work of Eric Ries in The Lean Startup, which defines a startup’s runway in terms of the number of pivots that can be completed before cash runs out.

On the talent front, skilled specialists boost performance, but may not fit into the startup culture. Those hired for attitude can ensure loyalty and enforce culture, but may not work well as the company scales and needs more standardisation, Tom observes.

On the investor front, there are challenges in raising too soon or too late. Investors should be chosen if they have a good track record and can provide a bridge round under duress, Tom suggests.

Having corporate partners helps, but there are risks in the power imbalance. Large firms may merely extract learnings at the startup’s expense, and founders may not know how to negotiate effectively or deal with corporate politics, Tom describes. These principles are illustrated via the case studies of a series of failed startups.

2. False starts

In a “false start,” the startup rushes to launch the product without adequate research and testing.

For example, the startup Triangulate launched by offering matching algorithms to dating sites but had a couple of false starts by not testing customer assumptions. Even after completing major pivots, it never found a large enough market, and was beaten out by competitors.

D2C apparel startup Quincy ran into tough times when it switched to an inventory-led model. The co-founders did not have industry experience and were unable to bring the right talent on board; the investors could not help much here either.

Tom suggests that the founders could probably have given new candidates a “tryout” for skills and attitudinal fit before hiring them full-time. Willingness to have tough conversations could have reduced co-founder friction, and the business partner could have been given equity as well.

Tom cautions that sometimes engineers have too much of a bias for action, and should instead launch products only after conducting tests via mechanisms like landing pages (see my book review of The Startup Owner’s Manual by Steve Blank). Other errors can arise from their introverted nature, or having too much arrogance without sufficient industry experience.

Models like Double-Diamond Design are useful here, with problem and solution tests via customer discovery interviews, focus groups, positioning statements, and MVP testing.

Convenience sampling, overlooking interviews with decision-makers, premature pitching, and relying only on early adopters (“category enthusiasts”) are other mistakes to avoid. Tom suggests corrective measures like competitor mapping and using skilled facilitators in customer discussions.

3. False positives

Pet care provider Baroo fell prey to the failure pattern of a false positive – its initial encouraging test happened to be with residents in a new neighbourhood. But later users from old neighbourhoods already had pet care providers, and switching costs were high.

Premature scaling to other cities became unsustainable, and some apartment concierge partners did not do adequate promotion. Without a well-developed playbook, the startup eventually shut shop.

Tom cautions that unexpected early success can be very seductive. Risk is heightened when founders believe their own hype, without adequate market tests. Some founders may also be unaware of their own growth goals.

II. Late-stage failures

Building on the opportunity-resource framework, Tom identifies four scale opportunities – geography, product lines, breakthrough innovations, and vertical integration.

1. Speed and scope

The ‘6 S’ success factors in the scale stage are of two types: internal (staff, structure, shared values) and external (speed, scope, series of funding rounds). Scaling can also be achieved via acquisitions, though there are cultural integration challenges as well.

Scale offers advantages (brand recognition, network effects, scale economies) but also comes with challenges (saturation, competitors, quality, morale, investor pressures).

The early team of jack-of-all-trades generalists needs to be supplemented with specialists and managers. Such roles include product managers, tech experts, HR heads, and a COO.

Formal organisational processes, structures and culture need to be built up. But conflicts between the “old guard and new guard” can lead to executive churn, Tom cautions (see my book review of What You Do Is Who You Are: How to Create Your Business Culture by Ben Horowitz).

Founders “who don’t want to grow up” should rely on guidance from mentors and board members. Habits of working in isolation or preferring only loyalists can be a challenge as well. Effective IT-based management systems need to be added too.

2. The speed trap

In the “speed trap” failure pattern, demand from enthusiastic early adopters (“the golden cohort”) fuels explosive early growth that cannot be profitably sustained in the mainstream market, Tom describes.

Competition can arise from fast followers, clones, or “sleeping dragons” who eventually wake up. In some cases, growth pressure can lead to unethical and even illegal behaviours by startups.

Tom outlines the RAWI framework to test scalability: ready, able, willing and impelled. Without a proven business model, resources, and willingness to grow, founders may fail.

Flash sales startup Fab.com was cloned by the “infamous Samwer brothers’ Rocket Internet incubator” in Europe. The startup burned cash to expand from the US into Europe via local offices and acquisitions, and spent prematurely on marketing.

Global players like Amazon also entered the fray, and Fab.com could not compete effectively in the inventory game. It failed the RAWI test, and later had to shut shop.

Tom suggests corrective measures at scale stage such as cohort analysis, tracking NPS, enforcing patents, managing board debates, and learning how to handle personal pressure during breakneck growth.

“Entrepreneurs must interpret trends correctly and act on them,” Tom emphasises. Otherwise, founders may end up digging a grave rather than a gold mine.

2. Resource challenges

Human and financial resource challenges can also plague scale-stage startups. First-time founders often do not have deep industry networks or savviness in dealing with investors.

For example, Dot & Bo, an e-commerce startup in home furnishing, faced severe supply chain strain while growing. Unreliable delivery times led to an alarming gap between post-purchase and post-delivery NPS. Poor tech infrastructure, bad hiring choices, and investor sentiment collapse eventually led to shutdown.

“Deciding whether to raise a cash cushion can be tricky because it forces an entrepreneur to choose between fear and greed,” Tom cautions.

As some corrective measures, he advises checking on investors’ current funds, choosing the right specialists at the right time, and strengthening company culture. “The challenge is finding the right balance between bureaucracy and chaos,” Tom observes.

3. Moonshots and miracles

Better Place founder Shai Agassi is an exemplar of a “monomaniacal founder” who fell victim to the failure pattern of “cascading miracles,” Tom explains.

The company bet simultaneously on strong demand for electric cars and swappable batteries, effective manufacturer partnerships, international markets, and effective execution. But it was plagued by rising costs, poor quality, regulatory challenges, and wrong demand forecasts.

A founder’s obsessive enthusiasm can lead to overconfidence about customer interest and blindness to barriers, Tom cautions. Other examples include Iridium, Segway and Theranos, though there have been successful moonshots such as Federal Express and Tesla.

“A moonshot, once launched, has a lot of momentum and can be difficult to steer in a new direction,” Tom cautions. Challenges arise via sunken costs and escalation of commitment to a flawed strategy.

Zeal and charisma can lead to a “reality distortion field” and move mountains. But narcissists have an inflated sense of self-worth and need for control and entitlement; they find it hard to reconsider strategy and recalibrate.

Tom suggests corrective measures like executive coaches, independent directors, and periodic founder/CEO assessments.

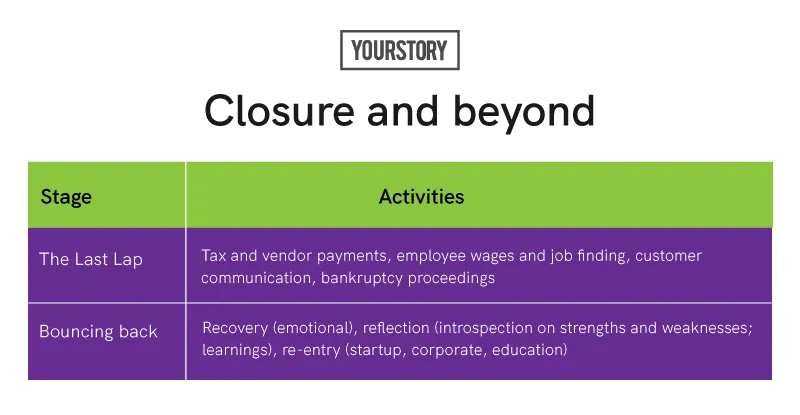

III. Closure and beyond

The concluding section of the book addresses what happens when the final decision is made to shut down the company, and how entrepreneurs can bounce back after failure.

1. The Last Lap

Typical last-ditch measures for a struggling startup include pivots, bridge rounds from existing investors, bringing in new investors, reducing headcount, or selling the company.

“Late pivots take longer to execute,” Tom cautions. It also takes time to complete due diligence for an acquisition and negotiate favourable terms. “Typically, failure is a slow-motion affair,” he adds.

Many founders desperately hope for an “eleventh-hour rescue,” and believe that entrepreneurs should not be quitters. At this troubled stage of loneliness and misery, many founders also lack a sounding board for good advice, Tom observes.

The founder’s ego can take a big hit, along with a sense of loss of face among employees for letting them down. There is worry about future finances, and recovery of careers.

The final stages of winding down entail tax and vendor payments, paying employee wages and benefits and helping them find other jobs, customer communications, and carrying out bankruptcy proceedings. Experienced lawyers and accountants will be needed at this stage.

After the last struggles and pulling the plug, the next phase of the endgame is emotional catharsis followed by recovery.

2. Bouncing back

Elisabeth Kubler-Ross describes the five stages of grief as denial, anger (who is to blame?), bargaining (what if? narratives), depression, and acceptance.

Failure can unleash a host of emotions and reactions: guilt, shame, regret, disappointment, embarrassment, confusion, and insecurity about the future, Tom cautions.

At the same time, many founders have expressed no regret about starting up despite eventual failure, and take pride in their experiences and learnings. They would rather have been participants in the game of change and opportunity than just observers.

As for coping measures, Tom advises therapy, journaling, physical fitness routines, and hobbies. After recovery comes reflection on lessons learnt about internal and external shortcomings, and testing the story and post-mortem analysis with trusted circles.

“Just find one thing about your failure that reminds you that you are still very good at something valuable,” suggests Fab.com CEO Jason Goldberg. He shared his personal failure story and lessons with friends, family, colleagues, investors, and coach – and eventually bounced back to start fitness instructor platform Moxie.

Steve Chambers (Jibo) became CMO at a green-tech startup, Christina Wallace (Quincy Apparel) moved into consultancy and education, co-founder Alexandra Nelson became venture effort leader at an MNC, Sunil Nagaraj (Triangulate) became a venture capitalist, Lindsey Hyde (Baroo) joined an educational foundation, Anthony Soohoo (Dot & Bo) became EVP at an MNC, and Shai Agassi (Better Place) founded a startup in public transportation.

The book ends with cautionary advice to aspiring founders to not blindly follow the conventional wisdom of just do it (but don’t truncate research), be persistent (but be willing to pivot), be passionate (but not overconfident), grow (but sustainably), focus (but also explore some other options and segments), and be scrappy (but don’t compromise on skills, quality, ethics).

Analysis for decisions should be written up and shared, and emotional discipline is called for. Tom advises entrepreneurs to think fast and think slow, and assures that moonshots will still be needed to tackle challenges like climate change.

“You’re likely aware that while failure may be painful, the entrepreneurial path is, for many people, an irresistible draw – a career calling. You may well be one of them,” Tom signs off.

In sum, this is a must-read book for all current and aspiring entrepreneurs, as well as investors and entrepreneurship educators. It offers a wealth of insights and tips into the world of startup struggles, and the mix of storytelling with business principles makes for an inspiring yet practical read.

YourStory has also published the pocketbook ‘Proverbs and Quotes for Entrepreneurs: A World of Inspiration for Startups’ as a creative and motivational guide for innovators (downloadable as apps here: Apple, Android).

Edited by Saheli Sen Gupta

![[Year in Review 2020] ‘Failure is a friend, philosopher and guide’ – 50 inspiring quotes on recovering from failure](https://images.yourstory.com/cs/2/28b451402d6a11e9aa979329348d4c3e/Failure3-1608901438313.jpg?fm=png&auto=format&h=100&w=100&crop=entropy&fit=crop)

![[Tech50] This startup aims to change the way teenagers consume news](https://images.yourstory.com/cs/2/77e43870d62911eaa8e9879653a67226/cover-01-1638793603725.png?fm=png&auto=format&h=100&w=100&crop=entropy&fit=crop)