Meet Myna Bolo, an AI chatbot that answers queries on sexual and reproductive health for women

Myna Bolo chatbot is an LLM-powered chatbot, which claims to provide medically accurate information about family planning, pregnancy, infertility, and menstrual hygiene to women in the slums of Mumbai.

A few months ago, Summaaiya, who hails from Mumbai, was anxious. Already a mother of four, she didn’t want another child.

Too shy to visit a doctor, she turned to the internet and other women for answers. She was told that contraceptives could cause tuberculosis.

Unsure of this information and whether she should avoid contraceptives, she decided to try the Myna Bolo chatbot. The bot quickly clarified that the information aforementioned was incorrect.

Summaaiya was relieved.

“The bot clarified my doubt and also connected me to an expert who could guide me on the right contraceptive for my needs,” she says.

Since then, Summaaiya has been asking 10 to 15 questions every day to Myna Bolo. She is among the 300 women from the slums of Mumbai, including Govandi and Lallubhai, who are using the chatbot to find answers to their queries on sexual and reproductive health–through the Myna Mahila Telehealth app on their phones.

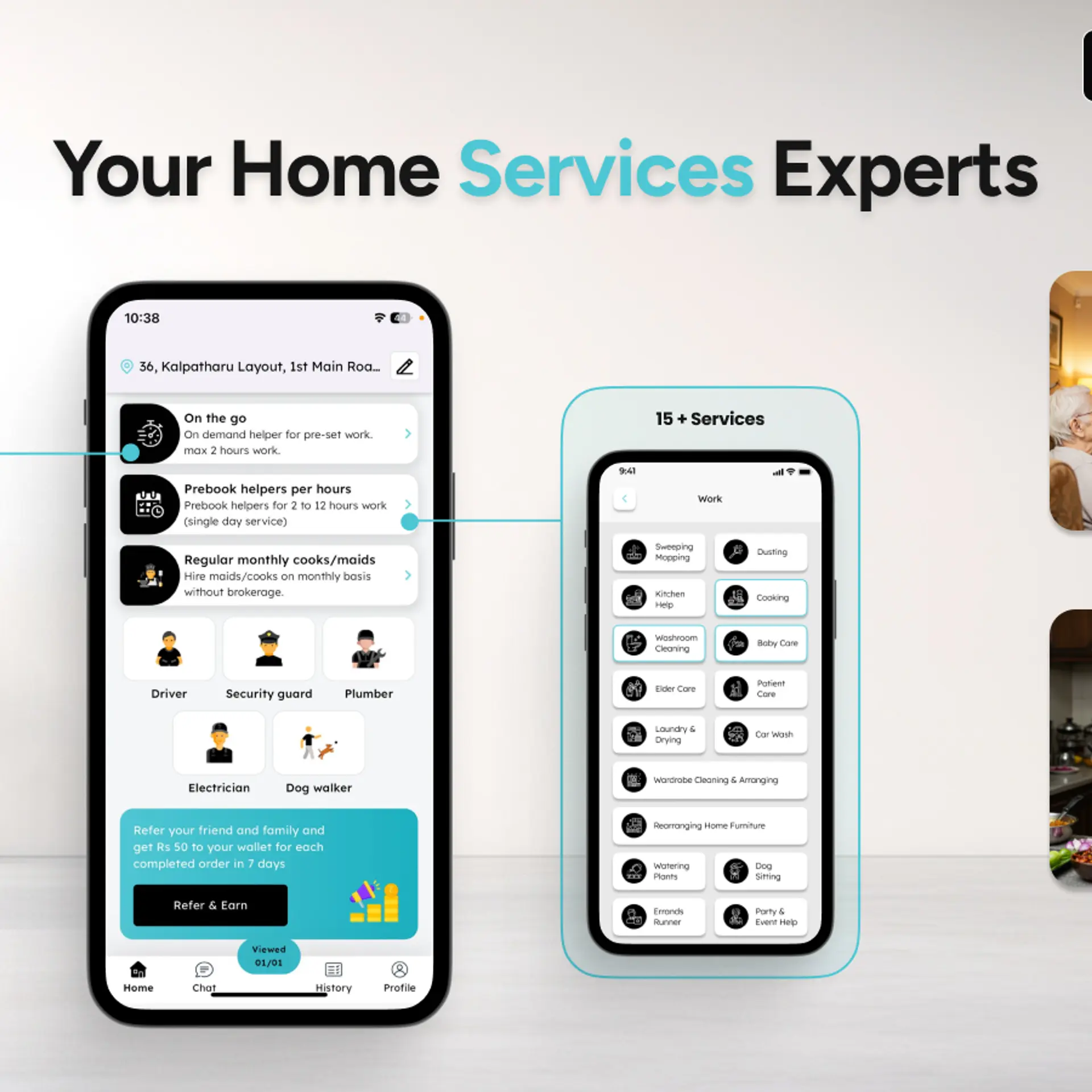

Myna Bolo chatbot is an LLM-powered chatbot which claims to provide medically accurate information around sexual and reproductive health of women on topics such as family planning, pregnancy, infertility and menstrual hygiene.

“I am too shy to ask my family or doctors. Also, most information online is in English, which is hard for me to understand. But, with the chatbot, I can ask in my own words in Hinglish (a blend of Hindi and English), and it responds in a way that’s easy for me to grasp,” says Summaaiya.

Development of the chatbot

Suhani Jalota (left), Founder and CEO of Myna Mahila Foundation, and Tanvi Divate (right), Lead and Director of the chatbot project.

The chatbot is being developed by a Mumbai-based women’s organisation Myna Mahila Foundation, which has been working in the area of women’s health since 2015. It is built on OpenAI’s ChatGPT 4 model.

Last year, the foundation had received a grant of $100,000 from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to develop the chatbot.

Currently the bot can understand Hindi, Marathi and Hinglish and return responses in Hinglish.

The project began in August last year; data was collected until January of this year, after which product development began. In May, the foundation did a soft launch of the chatbot.

Tanvi Divate, Lead and Director of the chatbot project, says that much of the information on ChatGPT is based on Western data, which may not always be relevant in the Indian context.

To address this, the Myna Mahila Foundation developed a retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) system, which ensures that the chatbot’s responses are aligned with the medical guidelines and the social and cultural contexts in India.

The RAG system uses the necessary information from a database of Indian medical guidelines and resources. To accurately process user queries, the chatbot uses a local dictionary created by the foundation. This dictionary, which has more than 500 complex medical terms, helps the chatbot understand and interpret specific words and phrases used by the women in the local community before generating an answer.

“We collected medical dictionaries with local slang, metaphors, phrases and common spellings (for example, copper-T is sometimes referred to as ‘coperty’) to train Myna Bolo to understand the local context,” explains Divate.

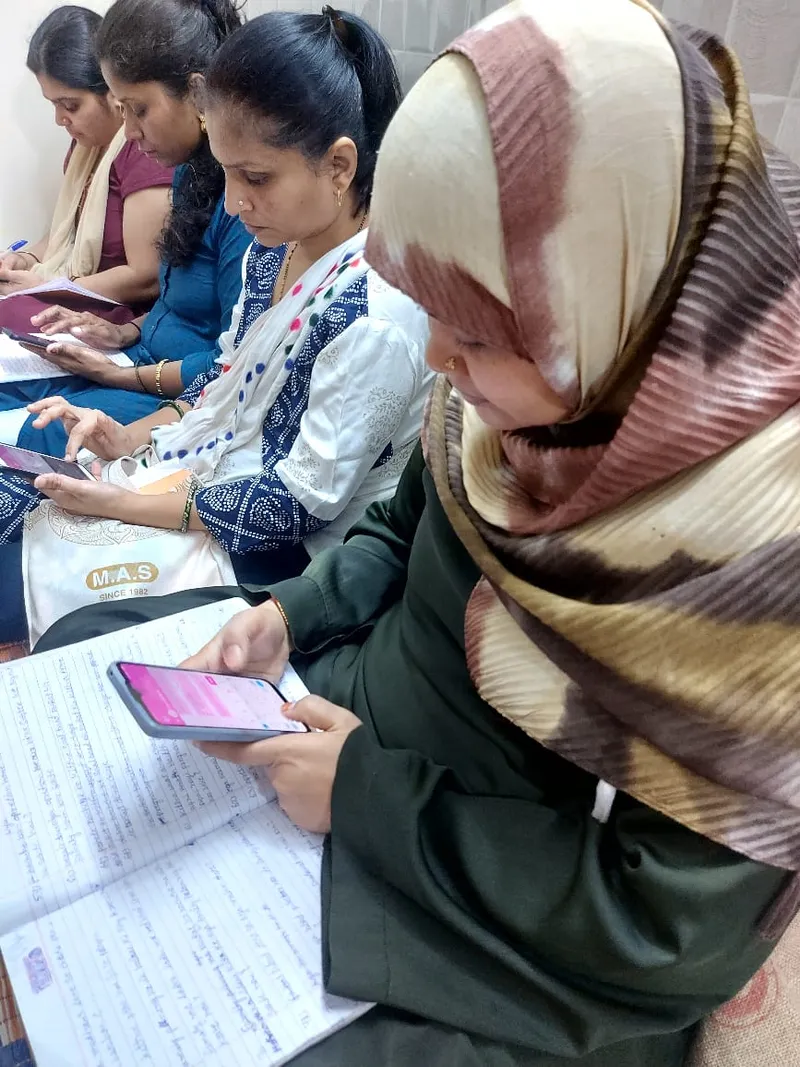

In the development stage, the foundation engaged women from the slums to train the chatbot.

Around 250 women, called ‘superusers’, from different employment, educational, religious, and family backgrounds were trained to become ‘healthcare prompt engineers’. These women asked queries related to sexual and reproductive health using local terms and slang to train the chatbot.

The superusers were paid to ask these questions.

Reshma, one of the superusers, has been working with the foundation for a long time now. She says she received Rs 5 per query during the training process.

While developing the chatbot, the foundation also provided the superusers access to in-house gynaecologists and clinics, trained them in the use of technology, and created awareness about misinformation.

Divate shares that the model has around 1.7 lakh locally generated datasets of queries in Hindi, Hinglish and Marathi.

Local women from the community are validating the chatbot's response in terms of understanding and offering localised responses. This approach aligns with the human-in-the-loop (HITL) strategy, ensuring accuracy and human empathy.

The chatbot is built on OpenAI’s ChatGPT 4 model

The foundation has also engaged local doctors to assess the chatbot’s responses for medical accuracy and social context.

The chatbot has a feedback system which asks the user if they understood the reply and which words were tough to understand.

“The bot responses are continuously monitored by medical professionals to mitigate any risks. This will soon also be supported by an automated system set up for real-time checking. We are looking at integrating evaluation agents to our existing flows,” says Divate.

She says that the bot has achieved 85% accuracy in queries related to family planning, pregnancy, period, and infertility and 90% accuracy in localising responses.

The Myna Mahila Telehealth app also has a period tracker through which women can keep a track of their menstrual cycle and a telehealth option by which they can connect to local doctors.

Challenges in the process

Divate reveals that, apart from the technical challenges of building an accurate chatbot, the whole process of data collection was also challenging.

“Sexual and reproductive health is not often talked about by these women. So bringing them in to generate queries on this topic was a tough task. We provided them sessions on what is sexual health and trained them in generating prompts. This process was exhaustive,” she says.

Highlighting the need for such a project, she shares, “Women in India still face obstacles in accessing sexual and reproductive health services due to stigma, discrimination, lack of prioritisation of their own health, and a lack of high-quality options.”

She emphasises that this problem is exacerbated for women living in urban slums as they have limited space and privacy. The women here mostly rely on their peers, WhatsApp forwards, or the internet, and these can be unreliable sources of information.

“This perpetuates lack of knowledge, continued stigma, and fear of judgement from family-connected health providers. Community members often reinforce taboos and misconceptions about menstruation and sexual and reproductive health,” she says.

Divate emphasises that there is an urgent need for an unbiased and factual source of information.

Impact of the chatbot

Superuser Reshma says the chatbot has been very helpful in answering questions about the best time to get pregnant, the best juices and fruits to consume during pregnancy, and much more.

“I ask the chatbot all the questions that come to mind, even late at night. It’s been a lifeline, offering answers to personal questions which I wouldn’t feel comfortable asking a doctor,” she shares.

The foundation plans to seek government support to scale the project in the future. It also aims to integrate the chatbot into WhatsApp to reach more users seamlessly, utilising the platform's simple interface that the community women are already familiar with.