How somatics is changing the course of mental health therapy

By examining the body’s expression of deeply painful experiences, mind-body therapists help people with complex trauma histories heal themselves in bite-sized, self-empowering ways.

Mrinalini Kumar defines her relationship with her body under two broad timelines—before and after somatic therapy.

Until four years ago, the stay-at-home mother from Chennai was severely dissociated from her body. She felt a disconnect and lack of continuity between her thoughts, memories, surroundings, actions, and identity.

Stanford University School of Medicine defines ‘dissociation’ as a disconnection between a person’s thoughts, memories, feelings, actions, and sense of self. It is a psychological defence mechanism common to individuals who have survived overwhelmingly traumatic events.

When Mrinalini turned to somatic therapy for relief and support, she learnt to address the effects of trauma first in her body—identifying symptoms like tightness in the throat and pain along the shoulder blades— which she then connected to the corresponding thoughts of dread and shame in her mind.

“This made it a lot easier for me to process what was happening,” she says.

Somatic experiencing is a trauma-informed modality that looks at the body from a biological evolutionary standpoint, wherein human beings are considered part of the animal kingdom, sharing a common biological framework through cellular structures, genetic codes, and basic physiological functions.

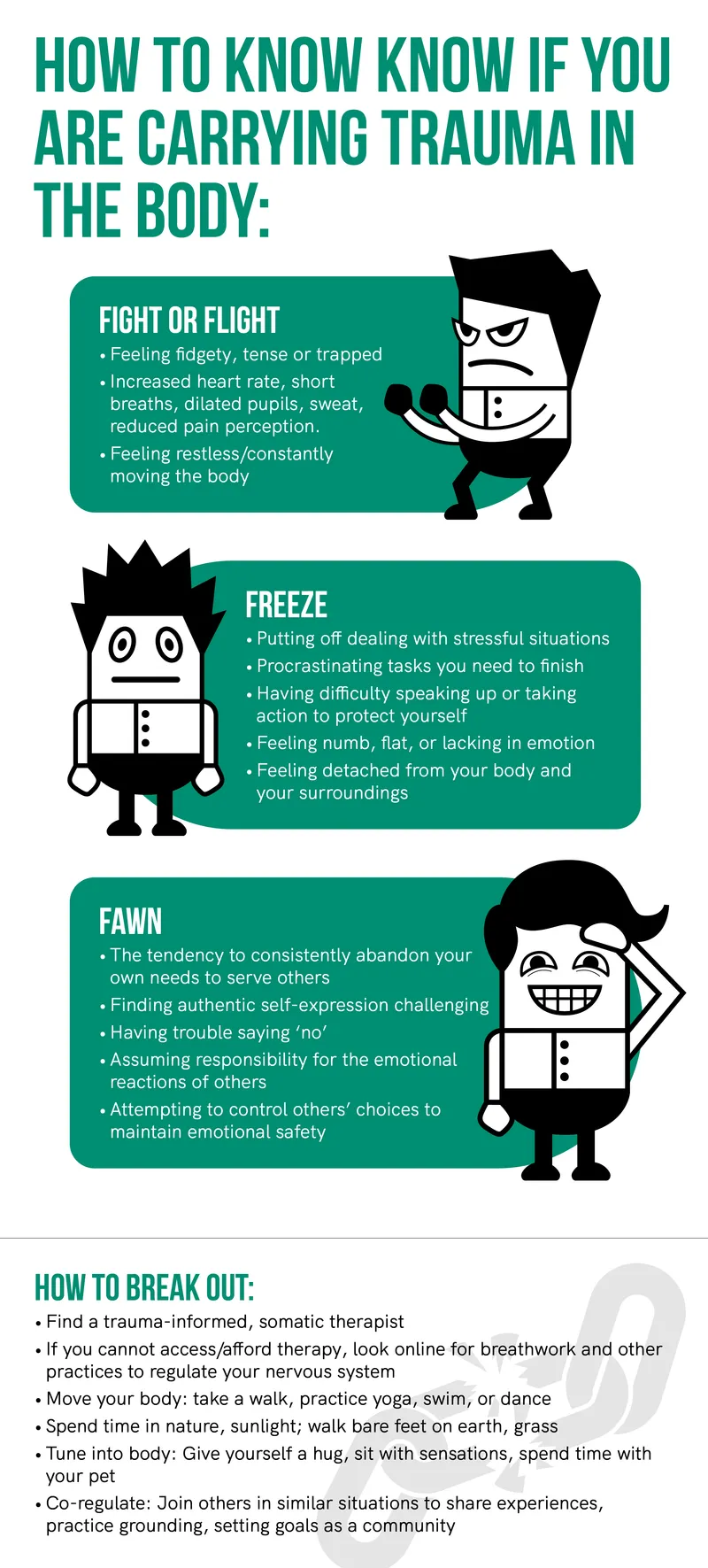

“When an animal is faced with a situation that threatens its existence, it fights, flees (flight), or plays dead (freeze),” explains Bengaluru-based Rajini Divya Kumar, a somatic therapist.

The fight-flight-freeze states are characterised by an increased heart rate and oxygen flow to major muscles, low pain perception, dilated pupils, tensed muscles, and sharper hearing—all of which direct the body to act quickly and appropriately to the threat.

But what happens if these actions are left unfinished?

“Most often, adults who live in dissociation were children who couldn’t complete the fight-flight-freeze responses and have been stuck in these states for years,” says Rajini.

What this means is, while the threat itself may not exist anymore, the body hasn’t learnt how to exit the response states.

A study by Manchester University's School of Health Sciences linked childhood trauma to increased dissociation in severe mental illnesses like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. It also made notable connections between specific childhood hardships and dissociation, with small to moderate effects in adulthood.

Experts say adults who were traumatised as children live with highly dysregulated nervous systems. The slightest trigger of their old, painful memories can result in unexpected rushes of adrenaline—the hormone that prepares the body to either fight or flee from danger; and cortisol—a naturally occurring steroid hormone in the body that fuels the brain and muscles to continue dealing with the stressful situation.

It wasn’t until she met a trauma-informed somatic therapist in 2020 that Mrinalini, now 40, was able to trace the physiology of her anxiety to her childhood years of severe bullying.

“Everywhere I went, I was picked on for my weight. This left me feeling ashamed and worthless for years. It dictated what I did and how, where I went, what I wore, and how much I wanted to be seen,” she says.

A chronically activated body can cause frequent panic attacks, anxiety sensitivity, agliophobia (fear of pain or suffering in the short or long term), and social anxiety disorder, among others.

“Trauma is not just an event that took place sometime in the past; it is the imprint left by that experience on the mind, brain, and body,” says Bessel van der Kolk, a Dutch psychiatrist, author, and researcher, in his book The Body Keeps the Score.

“This imprint has ongoing consequences for how the human organism manages to survive in the present. It changes not only how we think and what we think about, but also our very capacity to think,” says Kolk in his seminal work, considered a cornerstone for mental health professionals working with the body-mind modalities.

Not a matter of will

In trauma-informed therapy, the therapist considers the impact of trauma on the client’s emotions, behaviour, and even receptiveness to treatment. They operate under a basic assumption that a client might have experienced trauma and take care to avoid actions that could unintentionally trigger or re-traumatise them.

In Mrinalini’s case, the lack of trauma-informed therapy modules and community spaces pushed her down the spiral of shame and stigma, as friends, family, and even some mental health professionals asked her to just “start acting differently”.

After marriage, Mrinalini’s symptoms reached a breaking point when she became pregnant with her son.

“I couldn’t trust my body, which had been the subject (and site) of immense pain and shame, to conceive and bear a child,” she says.

Mrinalini says constant reminders from the people around her, including her then therapist, about how a ‘good marriage' and a new baby should keep her going, only aggravated her agony.

“My body was telling me otherwise, and I could do nothing to change how it felt,” she says.

Mrinalini learnt about somatics through a yoga teacher, who referred her to a therapist speacialising in the field. While initially progress was slow, Mrinalini felt her body’s tolerance for stress responses—short breaths, palpitations, cramps—expanded.

“The first thing we tell the client is that their inability to function to their full potential, their indecisiveness, their triggers—none of these are their fault. This takes a huge burden off their chests,” says Rajini, a psychotherapist (talk therapy specialist) for 22 years, who trained in somatic experiencing eight years ago.

“When you meet a talk therapist, you tell them your story, how you got here, and what you experienced along the way. In that situation, a client is often overwhelmed with emotions–whether it is anxiety, anger, or shame–as they are reliving those experiences.

“Since the body is not equipped to handle these emotions—the reason they became chronically stressed as adults in the first place—they tend to dissociate at the therapist’s too, just like they did as children,” she adds.

This is big reason why mind-body therapists work to increase an individual’s body awareness, guide them to feel the sensations connected to their triggers and sit with them. Individuals eventually become resilient to the triggers and find ways to resolve old fight-flight-freeze reactions in a safe environment.

The art of healing

Recovering from the emotional and physical effects of trauma necessitates aligning with the body’s natural healing abilities, which are often obstructed by the trauma itself.

Somatic art and movement therapies employ expressive arts techniques to uncover and address pain and illness within the body. They use the body as a guide, with mindfulness, art-making (crochet, painting, pottery), and body awareness practices (mindfulness, yoga, creative movement) to process difficult experiences and use one’s own capacities to resolve them.

“Art therapy improves cognitive and sensorimotor functions, fosters self-esteem and self-awareness, cultivates emotional resilience, promotes insight, enhances social skills, and reduces and resolves conflicts and distress this way,” says Neha Bhat, a sexual trauma therapist.

A few years ago, Tripura Kashyap, a dance movement therapist from Delhi, had a client who struggled to maintain healthy boundaries in her relationships and struggled to say ‘no’ to things she didn’t want.

Kashyap engaged her client in an exercise where she had to say ‘no’ in different tones–gently, firmly, meekly, and happily. She then asked her to express the emotion behind ‘no’ through her body–by pushing, resisting, or screaming.

“We decided she would start by declining things in low-stake situations–strangers in the bus, vendors in the market, and so on,” says Kashyap.

A few months later, Kashyap’s client was able to stand her ground in more pressing situations at home, as she trained to embody this freedom of choice.

In dance/creative movement therapy, one is encouraged to follow the natural, intuitive flow of their bodies to strengthen their body coordination, emotional expression, and trust-building in a safe, regulated space.

Combining movement with the cognitive, emotional, and somatic aspects of oneself allows one to understand their patterns and beliefs in an entirely new way.

For Delhi-based Prea Gulati, a behavioural scientist and somatic psychotherapist, exploring dance movement therapy with Kashyap created the space to organically identify and choose different responses.

“We can think of movement as the result of understanding mind and body as not separate units, rather one integrated, aligned unit,” she says.

Somatic therapists often acclimatise clients to also notice and tune into empowering feelings in the body by engaging in simple activities that feel good: making a soft bed, enjoying a favourite beverage/meal, feeling the earth/grass under the feet, and so on.

All these activities induce feelings of safety, comfort, and joy that also exist in the body. They act as a counter to the sensations of dread, fear, and anxiety, and eventually fortify one’s ability to heal.

Rajini, along with fellow somatic therapist, Chennai-based Bhakti Phatak, has been working on taking trauma-informed somatic modalities to victims of systemic inequities, including teens in bridge homes in Chennai and Bengaluru.

“These are young people who grow up in government orphanages and are about to leave them to build a life in the real world,” says Rajini. “Having experienced no semblance of a support system, they struggle with multiple traumatic disorders,” she adds.

By training mentors at bridge homes in somatic, trauma-informed therapies, Bhakti and Rajini want to help youngsters in these spaces break the cycle of powerlessness and dissociation, so that they can embody their identities as high-potential, sensitive, and empowered individuals at work, in relationships, and in the society at large.

This, they believe, is how they can effectively heal generations of unresolved trauma.

(Graphics and feature image by Nihar Apte)

Edited by Swetha Kannan