The 10 components of scale: What founders can learn from the successes of outstanding entrepreneurs

This must-read book is packed with frameworks, stories and tips on how startups can effectively scale up. Here are some key insights!

Launched in 2012, YourStory's Book Review section features over 320 titles on creativity, innovation, entrepreneurship, and digital transformation. See also our related columns The Turning Point, Techie Tuesdays, and Storybites.

Ace entrepreneur-investor Reid Hoffman offers a wealth of growth strategies and tips for startups in his latest book, Masters of Scale: Surprising truths from the world’s most successful entrepreneurs.

Reid is the founding board member and executive vice president of PayPal, co-founder of LinkedIn, and a partner at venture capital firm Greylock Partners. He serves on the boards of Airbnb, Microsoft, and Kiva. The book draws from his podcast series Masters of Scale; the co-authors of the new book are podcast co-producers June Cohen and Devon Triff.

See YourStory’s reviews of Reid Hoffman’s earlier bestsellers, BlitzScaling and The Startup of You.

The book shares insights and stories from a wide range of entrepreneurs, with takeaways and tips at the end of each chapter. The material is entertaining as well, and illustrates the complex twists and turns in an entrepreneur’s journey.

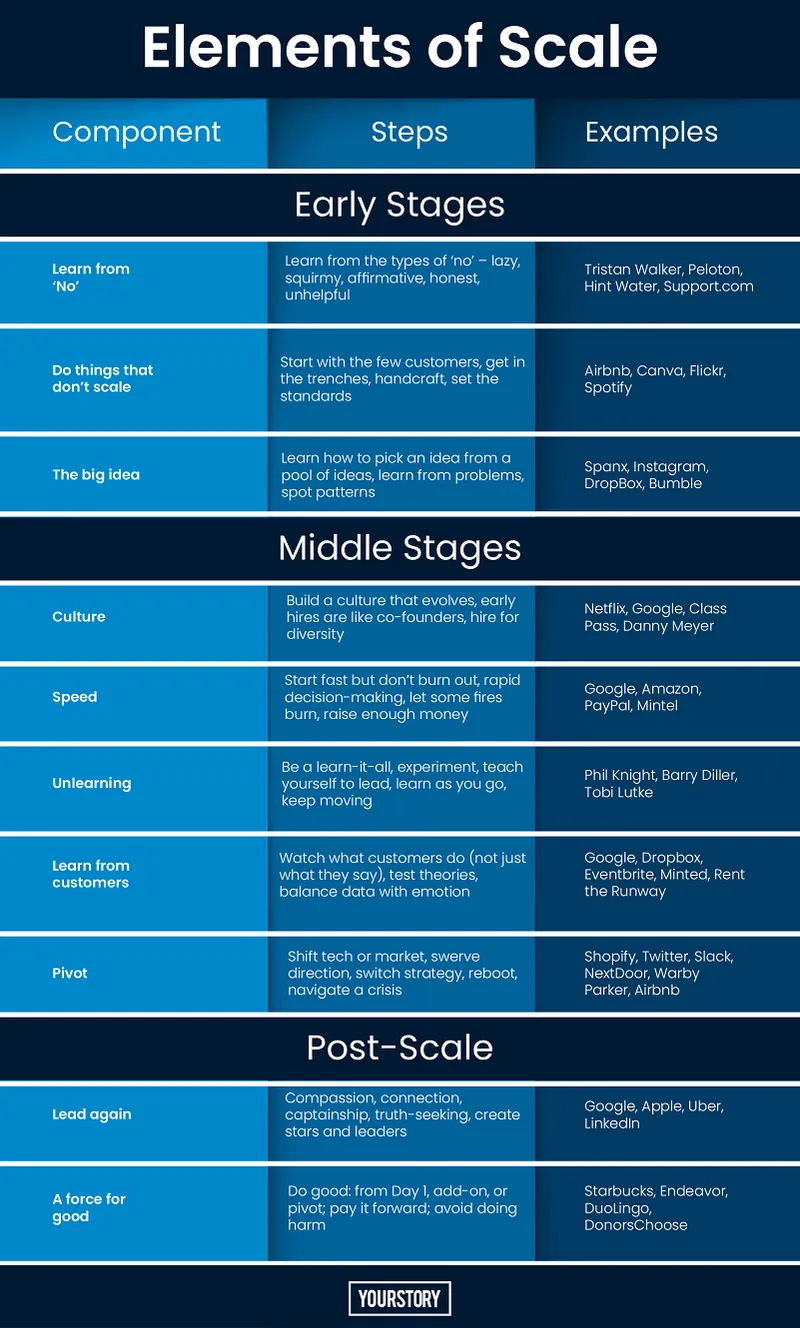

Here are my key clusters of takeaways from the 280-page book, summarised as well in the table below. See also my reviews of the related books The Invincible Company, Little Bets, The Creative Curve, What You Do is Who You Are, Out-Innovate, The Next Billion Users, Think Again, Customer Innovation, and Do Good.

Foundations

“Scaling is not just a science, but also a mindset – a journey that requires equal measures of faith and a willingness to fail,” the authors begin. They identify some counterintuitive truths about scaling – the best ideas seem implausible at first, an initial resistance is good, honest feedback has an outsized impact.

The book addresses scale issues at early stages (surfacing big ideas), middle stages (managing rapid growth), and post-scale stages (becoming a force for good).

“You do need knowledge, insight, and inspiration,” the authors advise aspiring founders; many successful entrepreneurs even began with minimal funding. The book draws on examples and interviews with two dozen “modern scale leaders,” such as Eric Schmidt, Reed Hastings, Brian Chesky, Ariana Huffington, Howard Schultz, and Bill Gates.

1. Learn from ‘No’

“The biggest new ideas are contrarian,” the authors observe. Examples include Airbnb, TED Talks Online, and Google’s search ad model. One of Reid’s regrets as an investor was not seeing the value of Etsy as a passionate community platform.

A “lazy no” gives no additional information, and an “unhelpful no” from a naysayer should be ignored. An “affirmative no” is an indicator that the founder’s theory must be improved, while the “honest no” could be a sign to move on to something better.

The “squirmy no” could indicate that there is a potential for greatness in the founder’s idea. “The gold is buried in the ‘Nos,’” the authors affirm. But there are nuances in each of these types of reactions, they caution.

Founders at early stages may face investors who are ignorant of the market or complacent with the status quo. But some of these reactions could be reflections of the founders’ lack of clarity on users or market differentiation, and can serve as failure warnings.

In the face of such reactions, founders like Tristan Walker (beauty products for people of colour) sharpened their skills in trendspotting, while John Foley (Peloton home exercise machines) turned to a host of angel investors.

Other resilient founders featured include Kara Goldin (Hint Water: water flavoured with fresh fruit), Mark Pincus (Support.com tech services), and Linda Rottenberg (Endeavor community for entrepreneurs).

“You can’t let rejection rule you. Instead, let it fuel you,” the authors urge. “The ability to both recognise a winning instinct and kill or refine a losing idea is an essential part of succeeding as an entrepreneur,” they add.

2. Do things that don’t scale

Ideas that scale first begin via working closely with a tiny cohort of users and meeting them right where they live. These pre-scale moments are sometimes considered the golden period of creativity when the opportunity is first defined.

For example, Airbnb’s founders themselves did the early photography work for their hosts. They also discovered a wealth of suggestions for improvement from home visits and long conversations with their early fanatical users. The same individual-first immersive approach was used to design Airbnb Trips.

One of founder Brian Chesky’s superpowers is design thinking. He uses brainstorming effectively to visualise the future of services via a ‘11-star’ experience, and thus identify the sweet spots.

“Passionate feedback is a clue that your product really matters to someone,” the authors advise.

At the early stages, founders should also set the standards and guidelines for their values, interactions, and moral compass. This should come through in industry relationships and trust-based partnerships as well.

Other featured innovators are Melanie Perkins (Canva), Caterina Fake (Flickr), Daniel Ek (Spotify), and Anne Wojcicki (23andMe).

3. The big idea

Big ideas can come from pursuing many small ideas, building on a series of ideas, or spotting the idea beneath another idea. They come from the grit of solving problems, or from networks and communities.

Successful founders have curiosity, pattern-recognition skills, a bias to action, passion, the ability to work under constraints, and a willingness to collaborate. They seek not just endorsement of their ideas, but criticism and suggestions for improvement.

“Go where ideas will find you,” the authors advise. It is important to create the time, space and habit for spotting and assessing ideas – which can happen in the living room, shower, dance floor, museum, or while travelling.

Examples cited in the book include Sara Blakely (Spanx), Kevin Systrom (Instagram after Burbn), Drew Houston (Dropbox), Sallie Krawcheck (Ellevest), and Whitney Wolfe (Bumble after Tinder).

Evan Williams built three companies around a long-term vision of connecting people and ideas: Blogger, Twitter and Medium. The trend of collaborative consumption has driven startups like ZipCar.

Jenn Hyman got the idea for Rent the Runway by watching her sister’s behaviour and aspirations for easy access to new clothing. She refined the idea via conversations with industry leaders, and also stumbled into new business models like a laundry service.

4. Company culture

As a startup gets past the launch stage, founders must build a culture that is built for scale. It should be diverse, flexible and adaptable.

“Culture is a living, breathing thing,” the authors describe. It should be grounded in a sense of mission, but can also be “maddeningly vague” to define.

Culture should be understood by everyone but also built by everyone in the company – it is a joint project. “It fully emerges only when every employee feels a sense of personal investment and ownership,” the authors emphasise.

Employees should be hired not just for cultural fit but for cultural growth. Early hires are “cultural co-founders,” and should share core beliefs about customers, business, ethics, and company personality.

“If you’re the company founder, you’re also a master distiller,” the authors affirm. Founders should be self-aware of their strengths and weaknesses, and hire diverse team players with a mix of generalists and specialists.

For example, the Netflix Culture Deck describes the importance of first-principles thinking, transparency, and honesty. Culture should be improved, not just preserved, according to founder Reed Hastings.

Danny Meyer (Union Street Café, Gramercy Tavern) built a successful restaurant culture around the values of excellence, hospitality, entrepreneurial spirit, and integrity. Principles of “enlightened hospitality” and staff support are verbalised, and “culture carrier” employees are rewarded.

To protect the foundational culture and passion of her fast-growing startup ClassPass, founder Payal Kadakia spelled out the vision and mission in a manifesto. It included principles of growth, efficiency, positivity, passion, and empowerment. While the conversation is encouraged around these principles, the core vision is regarded as non-negotiable.

Culture can also be reflected in the design of office spaces and names of rooms, such as currencies (PayPal) and host properties (Airbnb). Google hires people for their persistence and curiosity; Ariana Huffington values “compassionate directness.”

5. Speed

“Startups are a marathon of sprints,” the authors describe. Founders should strike a balance between “aggressive, rapid growth and strategic, watchful patience.”

Speed is of the essence. “But speed is not the same as haste,” they caution. Patience doesn’t mean slowness; it means strategically choosing the right moment for explosive action, as seen in the hunting pattern of a heron.

Fashionpreneur Tory Burch has an approach of “long-term brand first, short-term revenue second.” Amazon and PayPal have followed a model of scaling the user base first before becoming profitable, relying on the rule of compound growth and network effects.

Rapid decision-making helps outpace the competition and also fuel innovation, as seen in Google. For example, the decision to buy YouTube was taken in a mere 10 days.

“Nothing kills creativity like running into bureaucratic red tape,” the authors caution.

During times of rapid growth, it may be necessary to adopt a ‘triage’ approach and let some fires burn. But massive vulnerabilities can pile up, the authors add.

“Letting a fire burn takes nerves, vigilance, and lots of patience,” they warn. Issues of damage assessment, recovery and correctable errors need to be assessed.

Other featured scalers are Selina Tobaccowala (TicketMaster, SurveyMonkey, Gixo, Evite). Lessons learnt by entrepreneur Mariam Naficy (Eve, Mintel) from the dot-com crash and the 2008 crisis include raising more capital early enough.

Rana el Kaliouby (founder of facial recognition startup Affectiva) stuck to principles of ethics and chose to turn down a funder from an intelligence agency. They eventually found another investor with aligned values.

“Your relationship with your investors should be a partnership,” the authors advise. “Make sure you have enough funding to experiment,” they add.

6. Learn to unlearn

“It’s not enough to learn the ropes. To truly scale an organisation, you have to learn to unlearn,” the authors emphasise.

Success can lead to comfort and pride, and get in the way of new learning. “To purge the very knowledge or expertise that made you successful is very hard to do,” the authors caution. It is better to be a “learn-it-all” than a “know-it-all.”

Outclassed by Reebok in the 1980s, Phil Knight refocused Nike with an emphasis on design. The company shifted gears from a shoe company to a brand, thanks to high-profile ad campaigns like Revolution and Just Do It.

In the long run, “being in permanent beta” helps break fresh ground in new domains and become a serial entrepreneur. Moving into new fields brings in an outsider’s fresh and even disruptive perspective.

For example, Tobi Lutke began with an online snowboard store but spotted a greater opportunity in enabling e-commerce software. He eventually founded Shopify, and taught himself how to be a CEO by reading books like Andy Grove’s High Output Management.

Drew Houston of DropBox also taught himself via books like Competing Against Luck. He and his team pick a book to read for their regular leadership offsites.

Barry Diller kept moving into new territory with a string of successes in the media world: iconic films (Saturday Night Fever, Grease, Flashdance, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Top Gun), TV movies, The Simpsons, and QVC. He eventually set up the internet conglomerate and incubator IAC (TicketMaster, Expedia, Match.com, Tinder, OkCupid, Vimeo, Daily Beast).

When Bill Gates launched his foundation, he had to learn new ways of engaging with government and civil society, in countries like Ethiopia and Nigeria. Commitment to a long-term view requires patience to set up new systems and partnerships.

Founders should learn to experiment, and experiment to learn. Iterative techniques based on the MVP (Lean Startup) help in this regard. But that is not an excuse for shoddy products; the products should be at least “pretty good.”

However, not all industries are set up for learning from early mistakes. In retail stores, there is only one shot to make the right first impression, the authors caution.

7. Learn from your customers

Surveys are good for getting insights on customer sentiment, but knowledge about what they really do comes from actual observation.

Usage data revealed more accurate information on user behaviour than survey questionnaires of Google, Facebook, Dropbox, and Eventbrite users, the authors show.

Eventbrite successfully tapped the community of event planners entrepreneurs. Watching customers closely in real life and online helped spot emerging problems and opportunities, and innovate new offerings like RFID readers and even clamps.

“Treat your customers as your scouts,” the authors advise. “As a company founder, you are like a field general,” they add.

Those users who hack, hijack and even steal products yield useful clues as well. For example, Rent the Runway hit upon the subscription model by watching how customers used weekend rentals on subsequent weekdays.

Payal Kadakia hit upon the ClassPass models by observing how users wanted to experiment with different types of fitness classes each month. Watching how Bumble users tweaked the app helped Whitney Wolfe come up with new modes for professional networking and finding friends.

While the data reveals insights about customer preferences, it is also important to understand the underlying emotions, the authors urge. This can help platform founders approach brands with proposals for new offerings, as seen in the case of Rent the Runway and Jason Wu Grey.

Mariam Naficy, founder of online design marketplace Minted, found that, unlike Gen X users, millennials wanted to hear about the stories of the designers, not just see their designs. Robert Pasin of Radio Flyer came up with tricycle toys after listening to what his customers wanted, and discovering that they had conjured up an imaginary toy.

8. Pivot

Roadblocks, new opportunities, or deepened understanding can lead founders off-course to a new direction or pivot. The decision to pivot can be participatory but need not be democratic, the authors suggest.

“Human beings don’t let go of old ideas easily. In pivoting, you risk blowback from your co-founders, your staff, your investors, and your peers. For those reasons, it can be the single greatest test of your leadership skills,” the authors caution.

Sometimes, the side solution or embedded idea becomes more valuable than the original idea, the authors observe, drawing on the creation of Shopify as an example.

The founders of podcasting startup Odeo organised a hackathon, which yielded a group texting product – it was eventually spun off as Twitter. Game Neverending pivoted to Flickr, and Glitch pivoted to Slack.

Despite initial resistance, TaskRabbit pivoted to a new set of task rules and rating systems, and added services to improve training and development. It also set up a Tasker Council to involve the community in key decisions.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, NextDoor CEO Sarah Friar pivoted from neighbourly networking to crisis information and support services for health and business, via a COVID-19 Help Centre.

The authors even refer to the year 2020 as the “Year of the Pivot,” as founders adapted and improvised during the crisis.

Warby Parker switched to twice-weekly and shorter all-hands meetings, and instituted new procedures for disinfecting glass frames in stores. Airbnb increased its focus on long-term rentals, monthly stays, and virtual experiences.

A crisis is a time to rethink the structure and processes of a company, and also think big and look beyond the company and industry, the authors observe. This recalibration can be painful and sometimes devastating. But despite the fear and failure, there should be a place for compassion and caring.

9. Lead again

Creating community and connection are key attributes for leaders as they create the next wave of leaders, the authors observe.

“Every leader has to create a cultural drumbeat for their company,” they add. This drumbeat has to be consistent as a company scales.

The principle of servant leadership requires the removal of blockages to employees’ paths forward. In companies, this can involve not just seeking employee ideas but funding and backing them.

Leaders have to be truth-seekers as well as truth-tellers, and make it easy for people to speak up. Radical candour and constructive disagreement are key foundations for leaders, according to Ray Dalio, author of the bestseller Principles.

Angela Ahrendts led British heritage brand Burberry through a turnaround, and added elements of social impact. She then took over as head of Apple’s retail and online sales. She rallied employees via practices like video communication rather than standard email, to add elements of authenticity and human contact.

At stores, Angela added features like Today at Apple (free lessons), Teachers Tuesdays, Hour of Code for children, and boardrooms for entrepreneurs to learn from business leaders.

“Managers tell people what to do. But leaders inspire them to do it,” says Jeff Weiner, CEO at LinkedIn. Compassionate management begins with understanding the origins and aspirations of employees. Leaders must have clarity, conviction, and communication skills.

Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi was brought in to fix the “pirate ship” culture at a troubled time. The culture of scrappiness, rule-breaking, and “brilliant jerks” would have to be tamed through guidance and a code of ethics. Dara worked on improving the company’s relationship with drivers, and created a culture of collaboration rather than confrontation.

At Google, Marissa Mayer’s Associate Product Manager programme is highly-regarded and exposes product managers to a range of products. Yearly rotation brings them to different departments, thus also encouraging the spread of ideas across the company and creating an element of glue.

10. A force for good

Founders should create companies that combine profit with a conscience. This positive impact can be baked into the business and become its beating heart, and not just be a side effect, the authors advise.

“The best scale entrepreneurs think about their social impact from day one,” they observe, in the outstanding concluding chapter of the book.

Disturbed by childhood incidents of seeing his father getting injured and fired without compensation, Howard Schulz went on to make Starbucks the first American company to provide comprehensive health insurance to all its employees.

The company also offered stock options and free college education. In its China branches, it extended health insurance to the employees’ parents too, and had annual meetings with them. This helped improve employee retention and pride as well.

Linda Rottenberg (‘Chica Loca’) founded Endeavor to support entrepreneurs in Latin America. It backed one of the first e-commerce startups in the region, as well as Bitcoin wallet Xapo. It is in the interests of local businesses to support regional entrepreneurs and increase prosperity, she argues.

Franklin Leonard launched The Black List to promote first-time script writers in Hollywood. This helped his vision of a more inclusive industry and society.

Luis von Ahn from Guatemala migrated to the US and became a computer science professor. He launched crowdsourcing platform DuoLingo to help people learn better English, and other languages; course content is created by users themselves. The ad-supported platform is free to access, and there is also a subscription version without ads.

Charles Best launched DonorsChoose to match donors and worthwhile school projects. Anne Wojcicki started 23andMe to empower people with genetic information to control their own health.

As examples of good as an “add-on” feature, the authors cite TaskRabbit for Good (for disadvantaged or disaster-struck communities). Instagram’s Kevin Systrom is focusing on the use of technology to tackle online bullying.

There are also founders who pivoted later in their careers to doing good. Scott Harrison was a successful club promoter in New York City before switching to launch Charity: Water. The non-profit promotes transparency in the donation process for water projects, with a monthly subscription model for donors.

Robert Smith, CEO of Vista Equity Partners, has paid it forward through initiatives like funding support for the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, and paying off student loans. Liberating the human spirit is the greatest thrill on the planet, he describes.

In sum, this is a must-read book for startups and business leaders. The mix of storytelling with business principles makes for an inspiring and informative read for aspiring changemakers.

YourStory has also published the pocketbook ‘Proverbs and Quotes for Entrepreneurs: A World of Inspiration for Startups’ as a creative and motivational guide for innovators (downloadable as apps here: Apple, Android).

Edited by Saheli Sen Gupta

![[Product Roadmap] Focusing on cyber fusion centres, Cyware is helping enterprises upgrade cybersecurity](https://images.yourstory.com/cs/2/a9efa9c02dd911e9adc52d913c55075e/Cyware-1637666887435.png?fm=png&auto=format&h=100&w=100&crop=entropy&fit=crop)

![[HerStory Conversations] Fitness queen Malaika Arora bats for Ayurveda brand Kapiva and a holistic lifestyle](https://images.yourstory.com/cs/4/8e7cc4102d6c11e9aa979329348d4c3e/CopyofImageTagsEditorialTeamMaster5-1637908427379.png?fm=png&auto=format&h=100&w=100&crop=entropy&fit=crop)

![[Startup Bharat] From 5 orders a day to a customer base of 25,000 – A Toddler Thing is giving baby care a sustainable twist](https://images.yourstory.com/cs/2/3fb20ae02dc911e9af58c17e6cc3d915/GroupPic011568808062476png?mode=crop&crop=faces&ar=1%3A1&format=auto&w=1920&q=75)