When to listen to your customers and when not to?

Listening intently to the customers may often be self-limiting, if not outrightly self-defeating. You must know which customer to listen to, especially if you hear conflicting demands.

Customer centricity has become a buzzword these days. It is so much talked about in business circles and beyond that I wonder how did we get so far without exhibiting customer centricity? Is it a realisation, or a claim, or plain fizz? There are a few companies known for being truly customer centric such as Paytm, Royal Enfield, IndiGo, D-Mart, and iD Fresh Foods, come to mind here.

But if you analyse the success of such companies, you would notice a paradox. While customers love their products and services, the companies don’t necessarily start with the customer when it comes to designing those loyalty espousing offerings. So, to say, it all ends with a delighted or even pleasantly surprised customer, but not necessarily begin with those. That’s what brings us to the question of when to listen to customer and when not to?

Listening intently to the customers may often be self-limiting, if not outrightly self-defeating. You must know which customer to listen to, especially if you hear conflicting demands. Let’s understand the nuances better.

One of the big premises of listening to the customer is that the customer always knows what she wishes for. The so called ‘voice of the customer’ is only as good as customer’s self-awareness of what is indeed desirable and possible and is severely restricted by the vocabulary at hand. The customer mostly lacks the means of articulating a demand or a desire, for she isn’t clear of what to expect.

Think of how miserable you are in front of a doctor when she wants to know your exact problem. The best you manage is with symptoms and that too in your private articulation. That’s where the best doctors listen to you well and help you understand your own problem before attempting to address those. Imagine if you find it hard to articulate what’s ailing you or what you want, how much can you claim to know of a customer’s real woes. There’s an earnest gap between intent and content.

This gap is what Harvard’s Clayton Christensen explains in his book, The Innovators Dilemma. The innovator’s dilemma is whether to listen to the incumbent customer and remain committed to continuous improvements and incremental innovations, or to take a leap of faith and address entirely different set of customers.

Often the disruptive innovations aren’t tasteful to the existing lot, to begin with, and that’s where lies the risk. It’s a trade-off between pleasing the current market versus creating newer markets, of course, with a finite budget and managerial attention.

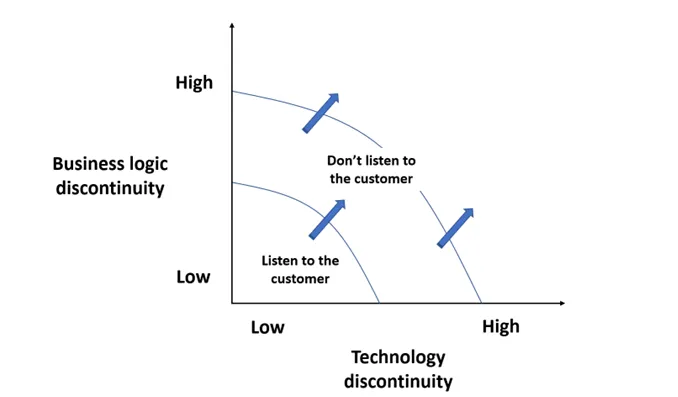

Let’s cast the insight back to our question at hand—when to listen to your customers and when not to. To understand this question better let’s refer to the figure below.

Customers and innovation (source: author)

It has two axes: Technology discontinuity and Business Logic discontinuity. Low levels of technology discontinuity refer to sustaining technological paradigms whereas high levels refer to disruptive or radical technologies. Think of yet greater capacities of storage, on hard-drives or solid-state devices, on the low end of the axis, while cloud computing or quantum computing based storage are on the other end.

Low levels of business logic discontinuity refers to the marginal departure from the way business is run and profits are drawn, whereas high levels indicate significant departure. For instance, Maruti Suzuki selling cars through a dealership network is a low level of business logic discontinuity, whereas crowd-pooling of cars operated by Maruti Suzuki would be towards the other end.

Essentially, you listen to your customer intently when you are dealing with existing business models and sustaining (read ‘incrementally better’) technologies. In such cases, both you and your customers know what to expect, and such inputs are hugely valuable in driving performance improvements.

If you take a UPI application to your customers and ask what else could be done on top of it, they can suggest a good number of incremental improvements. They have a base to work on and they think within the known paradigm. So, it’s safe for everyone involved.

However, if you are dealing with an unproven, radically different technology and/ or a radically different business model, then you must momentarily overlook what your existing customers have to say, and instead pay heed to the technological possibilities.

For instance, while moving away from mail delivery to streaming of movies, Netflix didn’t follow the wishes of incumbent customers. Because the customers were severely limited by their own experiences and, hence, had limited imagination. Such technological push or radical business models must start from the drawing board and radiate outwards to the market.

Think of how disrupted the retail investment market by not starting with the market expectations, but by devising an entirely fresh value proposition stemming out of an audacious business model. Once you throw it up to the customers, they can offer you great insights on how to make it better, but you must start by yourself with a leap of faith.

Now you understand what Henry Ford meant when he famously quipped, “If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.” It’s not born out of arrogance or lack of customer centricity, but out of an innate appreciation of technological possibilities and business model discontinuities. Almost a century hence, Steve Jobs echoed the sentiments, stating, “People don't know what they want until you show it to them.”

Since you don’t engage in radically new business models or technologies that often, the maxim of listening to your customers holds good. But every once in a while, you must be deaf to the external chatter and listen to your internal voice, for the real genius lies within.

Edited by Megha Reddy

(Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of YourStory.)